My first visit to St. Vladimir’s Seminary in the New York suburbs brought me in contact with a man who said he was destined for Alaska. I was visiting his dormitory room and he had a huge wall map of the state covered with pins. I asked what’s this? Why Alaska? What do all these pins mean? And he said “Well, these are the Eskimo parishes, and these are the Aleut parishes, and these are the Athabascan Indian parishes, these are the Tlingit parishes, and this is where we have clergy and this is where we don’t, and when I graduate, I’m going to Alaska.”

My first visit to St. Vladimir’s Seminary in the New York suburbs brought me in contact with a man who said he was destined for Alaska. I was visiting his dormitory room and he had a huge wall map of the state covered with pins. I asked what’s this? Why Alaska? What do all these pins mean? And he said “Well, these are the Eskimo parishes, and these are the Aleut parishes, and these are the Athabascan Indian parishes, these are the Tlingit parishes, and this is where we have clergy and this is where we don’t, and when I graduate, I’m going to Alaska.”

I said, “You mean there are Eastern Orthodox Christians in Alaska?” And he said “Yeah, remember … Alaska was part of the Russian Empire until 1867.” Well, I kind of vaguely remembered that … and I decided then and there that Alaska was for me. Here were the two most passionate interests of my whole life and they actually overlapped on American soil. I didn’t even need a passport to get there!

By the end of my first year in seminary, which was 1969-1970, I was determined to get to Alaska. On top of all of that, the first canonization of an Orthodox saint in the new world was going to happen on August 9, 1970, in Kodiak — all the more reason to make the summer of 1970 my first Alaskan summer.

I wrote letters — desperately — to anybody and anything I could get an address for in Alaska, trying to get some kind of job. I had no money and no means of getting there. There was a recession in progress. The state even had an information booth at the Seattle airport discouraging people from going up there to look for work. There were no jobs.

I didn’t have any success finding a summer job in Alaska by long distance correspondence. In fact, most of the times, I got no answer at all. With great disappointment, I gave up my hope for going to Alaska that summer … then a letter came to the seminary from Old Harbor on Kodiak Island.

They had been looking for a priest. The last resident priest, they told me, had died in 1837. These were very patient people! They’d been looking for a resident pastor to recruit to their village for some time, but hadn’t been able to find one. So they finally wrote to the Bishop and said, “If you can’t send a priest to our village, how about a seminarian?” The letter was forwarded to my school, I volunteered, and two weeks later, I was in Alaska!

I did get to attend the canonization of St. Herman. I spent the whole summer on Kodiak Island, visited Sitka on my way back, and when I returned to the east coast in August of 1970, I was totally committed and enthusiastic about Alaska and the beauty and the history and the cultures that were here.

From that point on, it was certainly understood by the faculty and students at my school that I was not only going to finish there as quickly as possible, but return to Alaska immediately thereafter — which is pretty much what happened. They even started calling me “Michael of Alaska” at school by the time I graduated. It was close enough to Oleksa for that word play to come into its place.

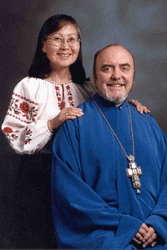

I came immediately following graduation in 1973. I taught at the newly opened Pastoral School in Kenai. I returned to Kwethluk where I had spent the summer of 1972 and met my wife — out on the tundra. We were married in April of 1974, and I was ordained in August and sent to Dillingham with responsibility for 14 villages in the Dillingham-Bristol Bay-Iliamna Lake region.

I had a parish that covered a larger territory than most states of the union! It gave me the opportunity to become familiar, not only with the Yup’ik Eskimos of the Kuskokwin Delta, the culture into which I had married, but also to become familiar with Athabascan people. I had spent a year also in Sitka among Tlingit folks in Angoon and Hoonah. And while I was living at the cathedral in Sitka, I was also working at Mt. Edgecomb High School, so I had some experience with a broad range of Alaskan Native cultures by this time.

I had a parish that covered a larger territory than most states of the union! It gave me the opportunity to become familiar, not only with the Yup’ik Eskimos of the Kuskokwin Delta, the culture into which I had married, but also to become familiar with Athabascan people. I had spent a year also in Sitka among Tlingit folks in Angoon and Hoonah. And while I was living at the cathedral in Sitka, I was also working at Mt. Edgecomb High School, so I had some experience with a broad range of Alaskan Native cultures by this time.

After several years in Dillingham, I was, at my own request, transferred back to Old Harbor, my original Alaskan home where my first son was born. My daughters were both born in Dillingham, and then my older son was born in Old Harbor on Kodiak. I became involved there in bilingual education. Actually, that started with Yup’ik language in Dillingham and continued in Alutiiq language in Kodiak.

Then, because I’d been in the state more than a decade and had spent almost all that time in villages, I was invited by Alaska Pacific University to teach cross-cultural communications, Yup’ik language, Alaska history, and some courses in their Religious Studies Program. So we went to Anchorage for a couple of years, and from there, because I’d already been doing in-services and summer school at Fairbanks, the University of Alaska recruited me to leave APU and migrate north to Fairbanks, where we lived for another five years.

In Fairbanks, I was involved in the cross-cultural education development program — the Exceed Program — that trained future teachers, most of them Native Alaskans, by distance delivery across the entire state. I had students in Fort Yukon and Barrow and Kotzebue and Nome, and it opened the whole northern half of the state to me for more exploration and experience.

By the time I came to Juneau in 1990, I had lived in 10 different cities of the state and had become quite familiar with Athabascan, Yup’ik, Aleut, Alutiiq and Tlingit cultures. I was teaching Alaska history and Alaska Native cultures and languages regularly as part of an orientation program for new teachers. I still do this every summer. I teach Alaska history and an Alaskan Studies course called Alaska Alive for new professionals in Alaska — school teachers, law enforcement officers, social workers, and next week I’ll be teaching EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) people. I teach for almost every agency, state and federal, that has intimate contact with rural Native Alaskans, offering insight and tips on how to better communicate and get along with that constituency.

Because of all of this, the governor appointed me to the Tolerance Commission last spring and out of that, invited me to participate in the Subsistence Summit in August. Last week, he invited me to the Governor’s Mansion for lunch and to be honored during the State of the State address!

After 30 years of being involved in rural Alaska, primarily with Native Alaskan issues, I was suddenly showered with honors, awards and plaques — a citation from the State Legislature, honors and recognitions from the Alaska Federation of Natives at its annual banquet this past October, and I was Alaskan of the Year last April here in Anchorage. After 30 years of almost thinking nobody’s really paying much attention or noticing, I’ve been honored and recognized beyond anything I would ever have imagined.

Source: LitSite Alaska