Our theme is the liturgy after the Liturgy. Consider the word “peace” in the Divine Liturgy: In peace let us pray to the Lord, for the peace from above, and for the peace of the whole world; and also the meaning of the celebrant’s greeting, “Peace be with you all.” We know the priest is not just transmitting his own peace, but he is transmitting to the congregation the peace of Christ. And peace, we know, is a gift from God.

Our theme is the liturgy after the Liturgy. Consider the word “peace” in the Divine Liturgy: In peace let us pray to the Lord, for the peace from above, and for the peace of the whole world; and also the meaning of the celebrant’s greeting, “Peace be with you all.” We know the priest is not just transmitting his own peace, but he is transmitting to the congregation the peace of Christ. And peace, we know, is a gift from God.

There is one phrase from the Liturgy in which the word peace figures prominently: “Let us go forth in peace.” There are many commandments in the Liturgy, things that we are told to do such as “Lift up your hearts,” “Give thanks to the Lord.” But, “Let us go forth in peace” is the last commandment of the Liturgy. What does it mean? It means, surely, that the conclusion of the Divine Liturgy is not an end but a beginning. Those words, “Let us go forth in peace,” are not a comforting epilogue, they are a call to serve and bear witness. In effect, those words, “Let us go forth in peace,” mean the Liturgy is over, the liturgy after the Liturgy is about to begin.

This, then, is the aim of the Liturgy: that we should return to the world with the doors of our perceptions cleansed. We should return to the world after the Liturgy, seeing Christ in every human person, especially in those who suffer. In the words of Father Alexander Schmemann, the Christian is the one who, wherever he or she looks, sees Christ everywhere and rejoices in him. We are to go out, then, from the Liturgy and see Christ everywhere.

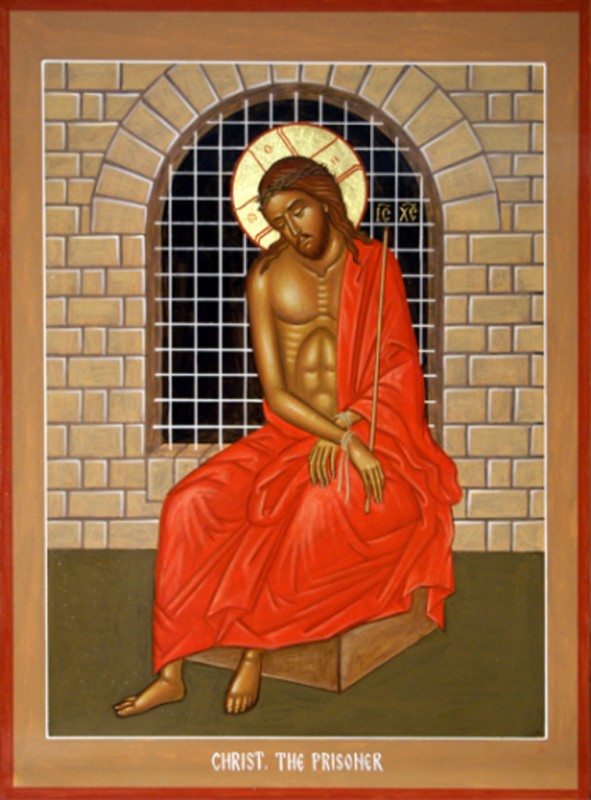

“I was hungry. I was thirsty. I was a stranger. I was in prison.” Of everyone who is in need, Christ says, “I.” Christ is looking at us through the eyes of all the people whom we meet, especially those who are in distress and who are suffering. We go out from the Liturgy, seeing Christ everywhere. But we are to return to the world not just with our eyes open but with our hands strengthened. I remember a hymn as an Anglican that we used to sing at the end of the Eucharist, “Strengthen for service, Lord, the hands that holy things have taken.” So, we are not only to see Christ in all human persons, but we are to serve Christ in all human persons.

Let us reflect on what happened at the Last Supper. First there was the Eucharistic meal, where Christ blessed bread and gave it to the disciples, “This is my body,” and he blessed the cup, “This is my blood.” Then, after the Eucharistic meal, Christ kneels and washes the feet of his disciples. The Eucharistic meal and the foot washing are a single mystery. So, we have to apply that to ourselves. We go out from the Liturgy to wash the feet of our fellow humans, literally and symbolically. That is how I understand the words at the end of the Liturgy, “Let us go forth in peace.” Peace is to be something dynamic within this broken world. It’s not just a quality that we experience within the church walls.

Let’s remind ourselves of the way in which St. John Chrysostom envisages this liturgy after the Liturgy. There are, he says, two altars. There is, in the first place, the altar in church, and towards this altar we show deep reverence. We bow in front of it. We decorate it with silver and gold. We cover it with precious hangings. But, continues St. John, there is another altar, an altar that we encounter every day, on which we can offer sacrifice at any moment. And yet towards this second altar, an altar which God himself has made, we show no reverence at all. We treat it with contempt. We ignore it. And what is this second altar? It is, says St. John Chrysostom, the poor, the suffering, those in need, the homeless, all who are in distress. At any moment, he says, when you go out from the church, there you will see an altar on which you can offer sacrifice, a living altar made by Christ.

Developing the meaning of the command, “Let us go forth in peace,” let us think of the Liturgy as a journey, Fr. Alexander Schmemann’s key image for the Liturgy. We may discern in the Liturgy a movement of ascent and of return. That kind of movement actually happens very frequently. We can see it in the lives of the saints, such as Antony of Egypt or Seraphim of Sarov. First, in the movement of ascent, if you like, or flight from the world, they go out into the desert, into the wilderness, into solitude, to be alone with God. But then there is a moment of return. They open their doors to the world, they receive all who come, they minister and they heal.

There is a similar movement of ascent within the Liturgy. We go to church. It’s pleasant to go there; though some people must use cars, I like to walk from my home to church before the Divine Liturgy, to walk alone if I can. It’s only about ten minutes, but I find it quite important to have that movement, a sense of going to church, a sense, if you like, of a separation from the world and starting on a journey. I walk to church, and I enter the church building, into a sacred space and sacred time. This is the beginning of the movement of ascent: we go to the church. Then, continuing the movement of ascent, we bring to the altar gifts of bread and wine and offer them to Christ. The movement of ascent is completed when Christ accepts this offering, consecrates it, makes the bread and wine to be his body and blood.

After the ascent comes the return. The bread and wine that we offered to Christ, he then gives back to us in Holy Communion as his body and blood.

But the movement of return doesn’t stop there. Having received Christ in the Holy Gifts, we then go out from the church, going back to the world to share Christ with all those around us.

Let’s develop this idea a little. Receiving Christ’s body, we become what he is. We become the body of Christ. But gifts are for sharing. We become Christ’s body not for ourselves but for others. We become Christ’s body in the world and for the world. So the Eucharist impels believers to specific action in society, action that will be challenging and prophetic. The Eucharist is the start of cosmic transfiguration, and each communicant shares in this transfiguring work.

Our title suggests a connection between peace and healing in the parish and the world, and I can’t possibly deal with all the things suggested by it. But let me, in light of the bit about “Let us go forth in peace,” pose a few questions about the different levels of Eucharistic healing and transfiguration in the world.

First a question about our parish life. Perhaps this is not true everywhere, but it’s true of some parishes I’ve known. I’ve often wondered why our parish council meetings, and more particularly the annual general meetings of parishes, are such a disappointment? To me it’s very surprising that often there’s a rather dark spirit at work in the annual general meetings of parishes. The picture given of our parish life is actually deeply misleading. All the good things seem to be hidden—perhaps that’s as it should be—but we get a very distorted picture. There seems often to be an atmosphere of tension and hostility at annual general meetings in parishes.

I’ve often wondered why that is. How to bring a truly Eucharistic spirit into such gatherings? How can we bring the peace of the Divine Liturgy into the other aspects of our parish life? I don’t have an easy answer, but I think behind this first question there lurks another question. How can we make the Divine Liturgy more manifestly a shared and corporate action? In my own experience, the parish where I am, we began worshiping just in a room, and at that time it was not difficult to have a very strong feeling of the Liturgy as a unified action in which everybody was sharing because we were all so close to one another, and there was only a few of us.

Some of the most moving Liturgies I’ve ever attended have not been in churches with great marble floors and huge candelabra but in small house chapels in a room or even in a garage. Now, gradually our community has grown. Twenty-five years ago, we built ourselves a church, and now that church is too small and we’re working towards enlarging the church in order to be able to have room for all the worshipers. Now that is, in a sense, encouraging, but there is a real struggle here. As a parish grows larger and as it acquires a larger building, it becomes much harder to preserve the corporate spirit, the sense of a single family, the sense of all of us doing something together. It becomes much harder to preserve that.

I haven’t any easy answers, but that is one level on which I ask, “How can we bring peace and healing into a community that’s growing ever larger, and therefore that is bound to lose its sense of close coherence, unless we struggle to preserve it?”

There is another level of healing that occurs to me quite frequently at the Divine Liturgy. We often have present non-Orthodox Christians and we are not able to give them Holy Communion by the rules of our Church. Now, I’m sure all of you have reflected on the reasons why the Orthodox Church takes this straight line over inter-communion. The act of Communion, we say, involves our total acceptance of the faith. It involves our total life in the Church. Therefore we cannot share in Communion with other Christians who—however much we may love them—we recognize as holding a different understanding of the Christian faith, and are therefore divided from us.

This is, we know, the argument why we cannot have inter-communion. But I think we should constantly ask ourselves if we are right to take this position? In fact I think we are, but I would say go on asking yourself in your heart if it’s the right thing to do. We Orthodox are becoming increasingly isolated on this issue. In my young days, most Anglicans would have taken the same view, and would have said they could not have Communion with Protestants. That’s certainly not the case now in the Anglican Church. Also, Roman Catholics held this view very strictly, but since Vatican II, whatever the official regulations may be, in the practice of the Roman Catholic Church there is widespread inter-communion. But we Orthodox continue as we were. Are we right? And if we do continue to uphold a strict line on inter-communion, in what spirit are we doing this? Is it in a spirit of peace and healing?

I remember at the beginning of my time as priest, the first occasion, and I still feel the wound inwardly, when persons came up for Communion whom I knew were not Orthodox. I felt that it was my duty as priest not to give them Communion. I was really interested in the reaction of two different parishioners. One said to me, “You did quite right! We cannot give Communion to these heretics. The Orthodox Church is the one true church.” He saw that in triumphalist terms. That made me feel even worse. But then another parishioner came up, and he said, in a very different tone of voice, “Yes, you were right, but how tragic, how sad, that we had to do this.” Then I thought, yes, we do have to do this, but we should never do it in an aggressive spirit of superiority but always with a sense of deep sorrow in our hearts. We should mind very much that we cannot yet have Communion together. Incidentally, both of those two parishioners are now Orthodox priests themselves. I think the first one, over the years, has grown a little less triumphalist. I hope we all do, but I’m not sure whether that always happens.

Then I’d like to reflect on a third level of healing. Let me take as my basis here the words said just before the Epiclesis, the invocation of the Holy Spirit, at the heart of the Liturgy. The deacon lifts the Holy Gifts, and the celebrant says, “Thine own from Thine own, we offer Thee.” And in usual translation, it continues, “in all and for all.” But that translation could be misleading. It could be understood as meaning “for all human persons, for everyone.” In fact in Greek, it is not masculine, it is neuter—“for in all things, and for all things.” At that moment, we do not just speak about human persons, we speak about all created things. A more literal translation would be, “In all things and for all things.”

This shows us that the liturgy after the Liturgy involves service not just to all persons, but ministry to the whole creation, to all created things. The Eucharist, thus, commits us to an ecological healing. That is underlined in the words of Fr. Lev: “Peace of the whole world.” It means, says Fr. Lev, peace not just for humans, but all creatures—for animals and vegetables, stars, for all nature. Cosmic piety and cosmic healing. Ecology has become mildly fashionable and often has quite strong political associations. We Orthodox, along with other Christians, must involve ourselves fully on behalf of the environment, but we must do so in the name of the Divine Liturgy. We must put our ecological witness in the context of Holy Communion.

I’m very much encouraged by the initiatives taken recently by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. Twenty some years ago, the then Ecumenical Patriarch Demetrios issued a Christmas encyclical saying that when we celebrate the Incarnation of Christ, his taking of a human body, we should also see that as God’s blessing upon the whole creation. We should understand the incarnation in cosmic terms. He goes on in his encyclical to call all of us to show, and I quote, “towards the creation an ascetic and Eucharistic spirit.” An ascetic spirit helps us distinguish between wants and needs. The real point being not what I want.

The real point, then, is what I need. I want a great many things that I don’t in fact need. The first step towards cosmic healing is for me to make a distinction between the two, and as far as possible, to stick just to what I need. People want more and more. That’s going to bring disaster on ourselves if we go on selfishly increasing our demands. But we don’t in fact need more and more to be truly human. That’s what I understand to define an ascetic spirit. Fasting indeed can help us to distinguish between what we want and what we need. Good to do without things, because then we realize that, yes, we can use them, but we can also forego them, we are not dependent on material things. We have freedom.

If we have a Eucharistic spirit, we realize all is a gift to be offered back in thanksgiving to God the Giver. Developing this theme, the Ecumenical Patriarch Demetrios, followed by his successor, the present Patriarch Bartholomew, have dedicated the first of September, the New Year in the Orthodox calendar, as a day of creation, when we give thanks to God for his gifts, when we ask forgiveness for the way we have misused those gifts, and when we pray that we may be guided for the right use of them in the future. There’s a phrase that often comes to my mind from the special service “When in danger of earthquake.” “The earth, though without words, yet cries aloud, ‘Why, all peoples, do you inflict upon me such evil?’” And we are inflicting great evil on the earth. Interesting to see earthquakes as the earth groaning because of what we do to it!

Finally, I ask you to think for a moment about one of our Gospel readings. What happens when the risen Christ on the first Easter Sunday appears to his disciples? Christ says first to the disciples, “Peace be unto you.” The first thing that Christ speaks after rising from the dead is peace. Then what does he do? He shows them his hands and his side. Why does he do that? For recognition. Yes, to show that here he is, the one whom they saw three days before crucified; here he is, risen from the dead in the same body in which he suffered and died. But there’s surely more to it than that. What he is doing is showing that, though he is risen from the dead, yet he still bears upon him the marks of his suffering. In the heart of the risen and glorified Christ, there is still a place for our human suffering. When Christ rises from the dead and ascends into heaven, he does not disengage himself from this broken world. On the contrary, he still carries on his body the marks of his suffering and he carries in his heart all our burdens. When he says before his ascension, “See I am with you, even to the end of the world,” surely he means, “I am with you in your distress and in your suffering.” Glorified, he is still with us. He has not rejected our suffering, nor disassociated himself from us.

We see from the Gospel how peace goes with cross bearing. Having given peace to his disciples, the risen Christ immediately shows them the marks of the Cross. Peace means healing and wholeness, but we have to add, peace also means vulnerability. Peace, we might say, doesn’t mean the absence of struggle or temptation or suffering. As long as we are in this world, we are to expect temptation and suffering. As St. Antony of Egypt said, “Take away temptation and nobody will be saved.” So peace doesn’t mean the absence of struggle, but peace means commitment, firmness of purpose, clarity of vision, an undivided heart, and a willingness to bear the burdens of others. When Paul says, “See, I bear in my body the marks, the stigmata, of Christ crucified,” he is describing his state of peace.

Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) is Titular Metropolitan of Diokleia under the Ecumenical Patriarchate. He lives in England. This essay was edited from a talk given at the Orthodox Peace Fellowship retreat in Vézelay, France in April 1999.