Source: Association of Interchurch Families

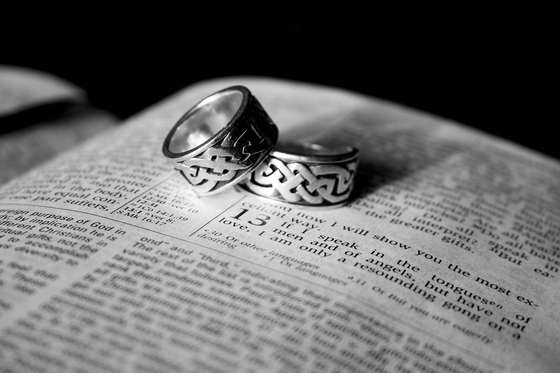

When You Intermarry: a Resource for Inter-Christian, Intercultural Couples, Parents and Families by Charles Joanides, published by the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North America (New York, 2002, $14.95) is intended to help to interchurch couples (here called inter-Christian or interfaith) and their pastors. Introducing the book, the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church in America (GOA) hopes that many lives will be blessed through its use, so that ‘the beloved families of our parishes become the wonderful and sacred reality that St Paul calls the “church in their house”.’

A research project

When You Intermarry is the fruit of work done by the Revd Charles Joanides for the Interfaith Research Project (IRP) of the GOA. Fr Joanides used focus groups and a web-site for his research, in which 376 intermarried couples (one spouse being Greek Orthodox) took part. Two-thirds of all marriages in the GOA are inter-Christian, and usually intercultural as well; the book intends to help them to see ‘their religious and cultural differences as an opportunity for growth rather than a threat to personal, marital, and family well-being’. It takes a stand against the negative view of intermarriage that was current until recently, and stresses the benefits, for both couples and their children, whose ‘lives are generally enriched, their perception of the world broadened’.

Of the 376 couples studied, Joanides found that most participants were positive about inter-Christian marriage, although they would be more negative about inter-religious marriage. Most valued religion and spirituality. Some were practising two different faith traditions, while others were essentially practising one, generally Greek Orthodox. There was widespread respect for the partner’s need to retain membership in his or her cultural and faith tradition. A few partners had become Greek Orthodox, and others were considering doing so, largely because they felt it would benefit the family.

Most did not regret being intermarried, but some – especially those with equally strong commitments to their faith traditions – felt a sense of loss. ‘I sometimes feel an emptiness when I’m at church alone. It is from feeling a bit distant from my wife and children in this part of our lives.’ Another spouse said: ‘When I started going to the Greek Church, I got rather resentful and frustrated because it just wasn’t the same and I felt deprived of something very important. This really affected us and I wondered what the consequences would be until I found a way to meet my own spiritual needs’.

What about the children?

Difficulties over the religious identity of children abounded, especially when couples had not discussed this before marriage. A non-Orthodox father said it became easier to co-exist ‘if we emphasise both the Greek Orthodox and Christian dimension of their religious identity. … We tell them that they are Greek Orthodox, but we also frequently just tell them that they are Christians’. An Orthodox wife said: ‘My church and parents taught me that Greek Orthodoxy is the one true faith, and I was insisting that our children receive this message … but it caused so much tension between my husband and me … We have compromised. We have agreed to tell our children that we are both Christians, but that they are also Orthodox Christians’.

Baptism was a huge problem for some couples, and so was the feeling of one parent that he or she was the odd person out in the family as the children grew up. Disagreements caused much tension in some families. The general feeling seemed to be that children must be brought up in one church (usually the Greek Orthodox) or their religious and spiritual development would be hindered. They should however learn to respect the Christianity of the other parent, and so gain a wider perspective. Parents found questions like ‘Why can’t Mommy and Daddy receive communion together in the Orthodox Church?’ and ‘Why do we celebrate Easter on two different days?’ difficult to answer. Extended families could cause a lot of problems, and the couple had to stand firm as a couple. Arguing in front of the children was disastrous; one child said: ‘When I grow up I’m not going to church. It’s not worth it’. But most couples agreed that it was possible to negotiate their religious differences successfully, and raise religiously and spiritually committed children.

Pastoral approaches

The second half of the book changes style, presenting ‘marital and family life cycle challenges’ in the form of fictional interviews with couples who are ‘composites of typical couples that participated in the IRP’. The interviews cover challenges that will face couples from the time they meet to the time when the children leave home, and each is followed by reflections and advice. The difficulties of non-Orthodox partners in adapting to their partner’s Greek Orthodox background are not underestimated. The ‘Greekness’ is often as much a difficulty as the ‘Orthodoxy’. Where church teaching and practice is concerned, the Greek Orthodox partners need to make big efforts to understand their own faith better so that they can explain it more adequately to their partners. They must also make a big effort to understand the cultural and religious background of their non-Greek Orthodox partners. Communication is vital. Couples must find a way of acknowledging and addressing the hurt feelings that may be caused by the Greek Orthodox Church not allowing the other partner to receive communion when the family attend the Divine Liturgy together. If the children have been baptised in the Greek Orthodox Church at the insistence of grand-parents, while the Greek Orthodox partner hardly practises, great resentment can be experienced by the other spouse as the children grow up. In such cases ‘it is important to identify the source of the problem without placing blame’. Parents need to be united and sure in their joint approach if they are to face the challenges presented by adolescent children, and if these latter are to develop personal faith and relate to a faith community. The tensions that may exist between parents and young adults are explored, as are those between a couple once the children have left home and the ‘isolated’ parent feels able to return to his or her church of origin. At every stage prayer and Christian understanding are presented as key.

Next, ‘balancing strategies’ are described: communication, patience, exploration and experiment, mutual love, acceptance, minimising the differences and maximising the benefits of an inter-Christian marriage, focusing on what is shared rather than on what divides, compromise, humour, fairness, respect of each other’s freedom to choose, developing healthy boundaries between the couple and their extended families, praying together.

Church regulations

Then comes an explanation of the pastoral directives of the Orthodox Church. There is a strong preference for intra-Orthodox marriages, but because of the Orthodox concept of economia, the Greek Orthodox Church now permits inter-Christian marriages between an Orthodox Christian and another trinitarian Christian. Marriages must be celebrated in an Orthodox Church by an Orthodox priest, or the Orthodox partner will not be able to receive the sacraments. The couples must agree to baptise and raise their children in the Orthodox Church. A non-Orthodox clergyman can be present at a wedding, with the bishop’s permission. He can give a blessing and address the couple at the end of the ceremony, but he is not to be reported as ‘participating’ in the Sacrament of Matrimony, since the Orthodox Church does not allow this. Non-Orthodox partners who marry in an Orthodox Church do not subsequently have sacramental privileges, nor can they be permitted an Orthodox funeral service, be allowed to vote in parish elections or serve on the parish council, nor serve as godparents or sponsors at baptisms and weddings.

Marriage preparation

Finally, the importance of pre-marital preparation is stressed, and a list of questions given for prospective partners to discuss before marriage. Most deal with religious difficulties, but the fifteenth and final question deals with ethnic and cultural differences. Most are ‘we’ questions, but some are questions for the Orthodox partner to answer, for example: Do I know how my non-Orthodox partner will react when I burn incense? Do I know why my non-Orthodox in-laws cannot receive the sacraments in the Greek Orthodox Church? An assessment questionnaire is offered to help couples judge their readiness for marriage.

Ministering to Intermarried Couples: a Resource for Clergy and Lay Workers is a companion volume written by Charles Joanides and published by the GOA in 2004 ($15.95). It ‘encourages qualitatively different thinking with regard to the marriage challenge facing the GOA’, and urges an outreach to help stop the slow drift of intermarried couples and their families away from the GOA.

It uses the same material as the book for couples, but there is more technical information about the IRP and its methodology in the clergy manual. It presents ‘A Developmental Social Ecological Theory of Intermarriages in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America’ as emerging from the IRP. There are sections on dating couples, engaged couples, newly-weds, parents with maturing children, and couples whose last child has left home. Each section is followed by Guidelines to help clergy and lay workers in their pastoral task. The emphasis is on careful and respectful listening, and raising questions and offering information in a non-judgemental way. Pastors should certainly raise the question of becoming a one-church family, but not in a pushy or intrusive way. Counselling worried Greek Orthodox parents of intermarried spouses should be done in a way that does not undermine or alienate the couple.

There is a chapter on ‘Pastoral Approaches and Programs’. Clergy are warned that many changes that intermarried couples would like to see ‘either conflict with Orthodox theology or may take an extended period of time to resolve’. The desire of intermarried couples for the non-Orthodox spouse to have access to Holy Communion and non-Orthodox extended family members to be able to function as godparents and sponsors are examples of the former. There are also calls for ‘more English, less Greek’, and the ability for the spouse to vote and assume leadership positions. However, the GOA need not espouse or promote exclusive, ethnocentric perspectives, or disparage other ethnic and religious traditions. Churches must learn to be more welcoming to non-Orthodox spouses, and teachers must not tell their classes that interfaith marriage is a sin. Intermarried couples must not be discouraged from exposing their children to both parents’ ethnic backgrounds. Positive suggestions include the formation of intermarried couples’ support groups.

Pastoral concern from an institutional perspective

Much work and pastoral concern has gone into the preparation of these books. The viewpoint is strictly that of the Greek Orthodox Church; it is expected that couples will comply with the requirements of that church, which are expressed in as reasonable way as possible. The Greek Orthodox partner is in the position of being cut off from his or her church if the couple do not agree to these requirements, rather as a Roman Catholic partner in a mixed marriage was before the Second Vatican Council and the progressive changes in marriage legislation since.

The Greek Orthodox Church has kept to the logic of a ‘one true church’ approach, and shows no signs of the struggles that have taken place in the Roman Catholic Church to adapt legislation to a post-Vatican II recognition that Christian churches and ecclesial communities exist outside her own boundaries. In Catholic-Orthodox marriages it is now Catholics who can adapt more easily to their partners’ position (although, as we see, in some cases with much parental opposition and with a great sense of loss, especially when the Orthodox partners are less devout). The GOA has a very strong ethnic and cultural identity, which compounds the difficulties for intermarriage, and it will be interesting to see the developments that take place in autocephalous Orthodox Churches in different parts of the world. The principle of ‘economy’ has already been used to allow marriage with non-Orthodox Christians, and no doubt there will be further applications in the future. Intermarriage is a real challenge to all communities; inter-Christian marriage offers an opportunity to make ecumenical progress.