I would like to focus on the stories of four women who are mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus Christ. There is something significant in the fates of those women, something that gets to the very core of the Gospel.

The Gospel of Matthew, and with it the New Testament, begins with the enumeration of earthly ancestors of Jesus Christ, that is, with His genealogy. Such a beginning was very important for the readers of those times who had to be convinced that He, Who is talked of, was a genuine descendant of King David, the very flesh of the Israeli people.

It was a must in ancient Israel, as in other nationalities, to keep genealogical records by the male line. The women, strictly speaking, didn’t need to be recorded at all. But in our case, among the host of male names we find four females: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and the wife of Uriah (Bathsheba). Why are they referred to at all while the most powerful queens or the renowned belles are not mentioned? Definitely, there is something important in their lives that brings us to the very core of the Gospel.

Yet, who are those particular women? What stories are their names taken from? The stories are all different but they have something in common. First of all, they are infamous stories, of the kind that people are unlikely to tell about their own ancestors. There’s something intriguing that makes them worth mentioning. Our task here is to find out an adequate answer to such a challenging question.

It would be appropriate to start with a quotation about all descents in general and about the importance of those long chains of names. Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh says, “examining all the names, we will be able to see real human beings, of flesh and blood, weak in life, worn out, and then suddenly rejoicing and triumphant. They all lived in the miracle of Christ’s humaneness and Christ’s humanity… Christ anointed that past lived through by the members of that big pedigree, so that all of them became God’s kinsmen. Likewise, we can also be able to apprehend and exonerate the past of our kinsmen with our own life, our labor, our feat, our craving and yearning for Him, our fighting for Him, and for His victory within us. That will be our donation to Him which will make us His kinsmen, even those among us who have never known Him or those who betrayed Him through either sin or a wicked heart and life.”

Tamar, the wife of her father-in-law

So, who were among His kinsmen? The story of Tamar is in chapter 38 of Genesis. It was at the outset of the Israeli people’s history. Actually, it wasn’t a people. It was an extended family of Jacob (later on he was re-named Israel). The members of the family were Jacob and his twelve sons born of his two wives. Jacob’s sons were with their wives and children. The next generations were, in due course, to bring forth Jacob’s grandchildren, great-grandchildren; thus, each of Jacob’s sons were to have become the progenitor of his own tribe–part and parcel of the Israeli people.

School of Rembrandt: Judah and Tamar

But the things didn’t go easily and happily, especially in Judah’s family. When his elder son died without leaving posterity, Judah, according to the law of levirate marriage, gave his son’s widow to the second son in the hope of preserving the family line. When the second son died, Judah, suspecting that Tamar was cursed, gave up the idea of marrying her to his third son, as the custom required. The time went on and Tamar remained single and Judah’s tribe didn’t continue.

Then she managed to seduce Judah in an unusual way. She dressed like a harlot, her face veiled according to the custom, and sat by the road waiting for Judah to pass by. And he did fancy the adventuress and spent a night with her, not recognizing his own daughter-in-law. As security, Tamar demanded that Judah should give her his staff and seal, the signs of dignity (identical to a passport and a credit card in our time). Some time passed and Judah was informed about Tamar’s being with child. Judah, without even looking at her, immediately ordered that the profligate should be burnt to death. Then it was Tamar’s time to react and she displayed Judah’s things. Judah had to own his fault–Tamar was not guilty. She committed forgery and it was a wicked deed, but the motive of that deed didn’t prove to be wicked. Tamar, unlike her father-in-law, cared about Judah’s lineage continuing.

She gave birth to twins who later became the ancestors of Judah’s tribe, the most prolific and powerful in ancient Israel. Her loathsome trick and incest following it are repulsive but they proved to be beneficial for the generations to come. As a result, what seemed to be a dirty dissipation proved to be a risk for the sake of the noble and sublime goal.

Rahab, a harlot from Jericho

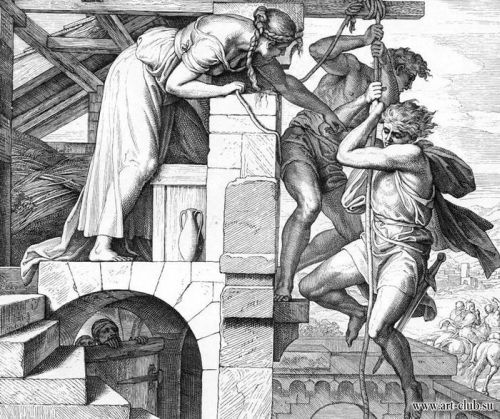

The next story also refers to a harlot, a professional harlot, and, furthermore, a Gentile. This story goes back to the time when the people of Israel were approaching the borders of the land promised by God (the “Promised Land”), after their escape from Egyptian captivity. They had to conquer the land, with the fist town on their way being Jericho. Before starting an assault, the Israelis sent spies to Jericho (Joshua 2). Unluckily, the spies were revealed and the gate of the town was locked up. It happened so that a certain harlot, Rahab by name, lived in the house built in the town wall. She invited the spies to her home to hide them. Nobody was surprised seeing two young strangers in the harlot’s house.

\”Rahab and the Two Spies\”, Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

Now we may ask why the woman from a social bottom did that at all. Did she do it out of pity for the young foreigners? Or did she feel the danger hovering over her home town and, thus, ventured to come to an agreement with the potential winners? Whatever may be, the events that followed after proved her case. Rahab helped the Israeli spies to escape by going down the town wall on a cord. In return, they promised to save the lives of everyone in her home during the assault.

And the promise was fulfilled. Moreover, after her deed, Rahab was incorporated among the Israeli people. Neither nationality nor a person’s past is important for God. He only values the person’s willingness to incorporate with His people, making her or him to undertake a noble yoke of the elect. Once a decision has been made, no one and nothing has the power to take it away.

The story of Rahab, like the story of Tamar, can be looked at as dirty and infamous, but the result is the same: taking risks for the sake of a noble goal brings forth success.

Ruth, an uncommon Moabitess

A whole book is devoted to Ruth. She was not an Israeli by birth either. She was a Moabitess. The Israelis didn’t think well of the Moabites because they were descendants of one of Lot’s daughters, who cheated her father and had sexual intercourse with him. The Moabites were often proved to be the Israelis opponents and tried to inveigle them into paganism. It is no wonder that their offspring to the tenth generation were not able to be full members of the Israeli society.

Nevertheless, Ruth’s story is a contrary assertion to general beliefs about “those Moabites.” Ruth managed to get married to an Israeli, who lived through lean years in the land of Moab. When her husband died, she didn’t go back to her relatives and start look for a husband as the tradition required. Ruth remained to live with her mother-in-law and vowed to abide by the laws of the true God of the Israeli people. She took risks to leave her motherland and move to the foreign land which couldn’t guarantee her a warm welcome. Unlike our days, there were no social services and a widow could only rely on the assistance of her relatives; but Ruth had no relatives in Bethlehem, the native town of her late husband.

Ruth in Boaz\’s Field, Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

However, in the tribal society there were mechanisms for caring about the poor. The next of kin had to look after a childless widow. According to the levirate marriage law (mentioned earlier), he had to marry her, so that, in Ruth’s case, she could have had children with her late husband’s family name. The law safeguarded the succession, but in reality few were ready to get married to an outsider’s widow. Do you remember the story “Little Boy and Karlson” where Little Boy with a feeling of impending disaster thought about the necessity of inheriting his elder brother’s wife, as he inherited his clothes.

When Ruth’s husband’s kinsman refused to marry her, she struck up a friendship with another relative, a wealthy man, Boaz by name. Being poor, she was allowed to glean grain from his fields (in Stalinist Russia gleaning was a crime to be punished). Ruth and her mother-in-law lived on that grain. After a romantic date with Ruth arranged by her mother-in-law, Boaz took her as his wife. He appreciated her loyalty to the deceased husband and his mother, as well as her willingness to abide by the customs of the Israeli people. The Moabitess became a full member of the Israeli society and a great-grandmother of King David, that is, one of Jesus Christ’s ancestors. Ruth’s story is an integral part of the Gospel.

Who would dare to call the Moabites impudent and cruel gentiles on knowing Ruth’s life? All kinds of discourse on bad nations come to a deadlock when dealing with such personalities as Ruth, who made her choice deliberately and purposefully, once and forever. Loyalty to God and His people is much more important than outward decency and cold, blood interest.

Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah.

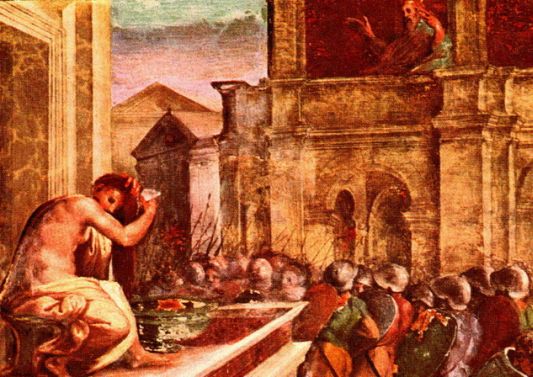

The next woman in our list, Bathsheba by name, was a queen. But the Evangelist calls her ‘the wife of Uriah’, and that isn’t by accident. He seems to display the most infamous events in the family narrative, the events which are normally covered up. King David lived through a tumultuous and, very often, unchaste life, but the Bible reveals his relations with Bathsheba as a deadly sin, which dramatically changed his life.

The story tells that the King noticed a beautiful young woman from a high roof of his house. She was taking a bath in the courtyard of the house she lived in. He ordered to bring the woman to his privy rooms and, having satisfied his lust, sent her back. The woman conceived while her husband Uriah, who was David’s faithful warrior, was on campaign. In an effort to conceal his sin, David summoned Uriah from the army in the hope that Uriah would fertilize his wife and think the child to be his. Uriah refused to leave his companions-in arms on the battlefield and go home to his bed. Then David had Uriah himself carry the message that ordered his death. Thus, a brave and faithful warrior lost his life and the King got a new wife.

David and Bathsheba, Raphael

And David was punished for his sin: Nathan the Prophet came to David to reprimand him over his committing adultery and proclaimed a coming visitation for him. David repented sincerely and that penitence of his, known as Penitential Psalm 50, is read by millions of Christians throughout the world. Bathsheba’s second son from David, named Solomon, ascended his father’s throne and was the most powerful and renowned among the Kings from the Old Testament.

Steps to the Gospel

Why have all these women’s names been presented to us? Seemingly, they discredited their descendants. Indeed, one of them had a child from her father-in-law, the other was a harlot, the third belonged to a scorned people, and the fourth was involved in an abominable sin. Wouldn’t it be better to rub away their names out of the genealogy, to cross out and forget them forever? Why not remember the names of quiet and modest women – respectable housewives whose lot was bearing children and not seeking adventures?

But the Bible does not only tell good stories about the heroes. It reveals the essentials. Not even omitting the ugly details, the Bible, thus, reveals something significant in their behavior. The first three women took risks which later on proved to be justified. Tamar’s seducing her father-in-law resulted in preserving Judah’s tribe from extinction. Rahab’s sheltering her people’s enemies led to the destruction of her native town and the extermination of the residents. But God’s plan was fulfilled when she and her family became part of the Israeli people. Ruth risked not only her reputation when she had a night date with Boaz. Had the residents of Bethlehem rejected her as a harlot, she and her mother-in-law would have lived a miserable life, with their generation would have vanished from the face of the earth.

As for Bathsheba, she was completely in David’s disposal having shared his sin and drinking her own cup of woe: she lost her husband and a child. The story had an abominable and woeful beginning but a merited ending that was crowned with the birth of King Solomon.

All four stories are stitched with the same thread. People find themselves in difficult situations, they are often at a loss and are not able to chose the right way out. Their lives and fates seem to be dubious and disreputable. But the point (as we see it now) is that their lives are guided by God’s will and not by their own wishes and plans. And it is only when they are ready to accept God’s plan, like Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and even Bathsheba after David’s repentance, that their lives make sense: disgrace may lead to glory, all sins may be forgiven and left behind.

In this world of ours, God sometimes acts through His Angels but mostly He acts through common folk, who are sinful, lustful, restless, and mistaken. It is in God’s power to lead us by means of our dreams and doubts to achieving a high goal. He has the power to change us, to make us His people if only we are willing to trust Him.

And yet why all this women talk? Isn’t it because there are too many male names and those meaningful are lost among obscure ones? No, that can’t be the only reason. A woman is not always involved in the big events of the world history, but there is no family history without a woman. The stories of the four women are but a prologue to the story of the Nativity. And what is the story of the Nativity if not a story of a family and a common Maiden of Nazareth who accepted an amazing and awesome message from Archangel Michael? It is now that we know her as the Blessed Virgin but then she was only Joseph’s bride who accepted an unusual pregnancy. For that she could have been stoned as an adulteress. Merciful Joseph wanted to let her go by dissolving the betrothal. In that case it would’ve been the end of the story, but Mary had taken a risk to accept the inevitable which resulted in Our Lord’s Nativity.

Translated from Russian by Ludmila Koemets

Edited by Jacob Aleksander Brooks and Isaac (Gerald) Herrin