The Sunday before the beginning of the great lent has two themes: one theme is the expulsion of Adam from Paradise and the other theme is forgiveness.

The Sunday before the beginning of the great lent has two themes: one theme is the expulsion of Adam from Paradise and the other theme is forgiveness.

In popular terms in Orthodox tradition, this Sunday is called the Sunday of Forgiveness, Forgiveness Sunday. And then at the vespers in the evening of that Sunday you actually have the beginning of the great Lenten season which is very often accompanied by a ritual of forgiveness where each person in the church approaches every other person, and, bowing before them, asks for their forgiveness and receives the forgiveness of the other.

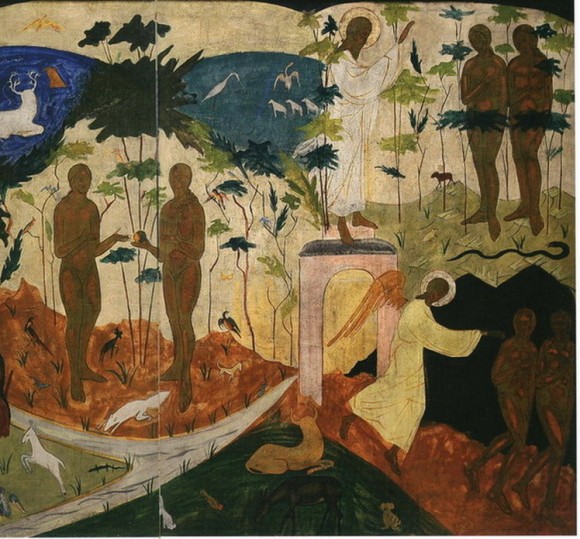

The expulsion of Adam from Paradise. The hymns at the service on the Sunday before Lent and the canon at matins all have to do with a meditation of the expulsion of Adam from Paradise, and in those hymns the worshiper identifies himself or herself with Adam and with Eve. The songs are very often in the first person: “I was with you in Paradise, I sinned against you, I have lost my original beauty, I am cast out of the garden—which in Greek means “Paradise”—I am sitting here East of Eden weeping and lamenting my sins.”

This expulsion of Adam from Paradise is very similar to—in its content and in its message—the parable of the prodigal son, that the being outside Paradise is very similar to being in the pig pen, to being away from the house of the father, being in a far country, wasting what one has, having been foolish, wasteful, sinful and finding oneself devoid and bereft of the beauty and the glory of God and the house of the Father.

This expulsion from Adam also is similar to the meditation on thePsalm 137, “The waters of Babylon,” which is sung at this season. Where the worshiper identifies with the exiles, who are no longer in Jerusalem, who are in exile, who are under control of the Babylonian wicked powers, who are lamenting the remembrance of Jerusalem, like the prodigal son is remembering and lamenting the loss of the father’s house. Well, on this particular day the believers and worshipers of God are lamenting the loss of Paradise.

Some of the songs and some of the hymns which are very many, are very moving, very touching in what they say. Just for an example, at vespers it’s sung, “O precious Paradise, unsurpassed in beauty, tabernacle built by God, unending gladness and delight, glory of the righteous, joy of the prophets, dwelling place of the saints, with the sound and rustling of your leaves in the trees of the garden, pray to the Master of all. And may he open into me the gates which I closed by my transgression; may he count me worthy to partake in the tree of life once again and of the joy which was mine when I dwelt in thee from the beginning.”

Now, of course we human beings are not Adam and Eve; we are born outside paradise, we are in a sense victimized by their sin and by the sins of their children and their children and their children who have become our parents and our grandparents and our ancestors. We are members of the human race; we are humanity, but we know that from the beginning— and this would be the teaching of the Genesis story; there are two of them in the Bible—that Adam and Eve from the beginning, humanity from the beginning was created to share the glory of God, was created to be as the holy Fathers say gods themselves by grace, if humanity would just believe in God, love God, show the love of God by keeping his commandments, obeying God, trusting God, not listening to the evil powers, not listening to the wisdom of this world. For that serpent in the story stands for earthly wisdom, which in the letter of James is called earthly psychic as opposed to spiritual and demonic, diabolical. So that serpent is Satan: it’s earthly wisdom, it’s one’s own choice, it’s one’s own will over and against God, it’s listening to all those voices which are not the voice of God, obeying all those words that are not the word of God, and therefore bringing death upon oneself.

The expulsion from Paradise in the story is done by God, but he has no choice. The sin itself—and that’s what the partaking of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil means, it means an act of apostasia—apostasy, rebellion, madness, foolishness—that act kills humanity. In the story the Lord says, “In the day that you will eat of it you will surely die; even if you touch it you will surely die.” Now some people say, “Well, Adam and Eve ate it. They did not die,” but they did. They became dead the minute they did it. Yes, they became mortal; they lived longer. It says Adam lived, I don’t know, a hundred and some years and so on, but they were already dead. They were living dead men, as we say; they were existing but no longer living, because living in Scripture means to praise and glorify and obey God.

In an Orthodox tradition and the Scriptures and the Liturgy, even in the writings of some of the saints—even one of the recent saints Silouan of Mt. Athos who died in 1938, he has written this long lament of Adam “Oh, how I long for Paradise, how I long for my original place. I can remember it; it’s in my mind but I don’t have it. And here I am cast out, cast out by my own sin, by my own rebellion, left out to die.” And some of the saints like St. John Chrysostom said the fact that it’s a law, an ontological metaphysical law, that if you sin you die; in St. Paul’s language, “The wages of sin is death.” There is a certain mercy in that, because if we could just sin and sin and sin and do evil and wickedness and grow forever without end, it would be just an endless hell, which some people still, God forbid, may choose, but the fact that we die gives us a chance, gives us a chance to be reborn, gives us a chance to start all over.

And here in this contemplation of being exiled with Adam at the same service we sing the song “On the waters of Babylon.” It is not only for us to remember our apostasy, to remember our rebellion, to remember that we are not in the father’s house, we are not in paradise, we are not in Jerusalem; something has gone terribly wrong and is gone terribly wrong because of the rebellion and sin of humanity. It’s not only that we’re to remember that, but we are to remember also that God forgives us, that God has mercy on us, that God knew that humanity would sin, God knows all things. He didn’t create Adam and Eve and put them in Paradise and then say, ” Oh my! Look, they sinned. What shall we do?” And that God the Father would then say to the eternal Son and Word, “My Son, go and do something about this humanity who has sinned.”

God knew that we would sin before he made us, and he made us anyway. With that sin is part of his providential plan for our salvation. We have to go through it; we have to experience it. As one the English mystic named Dame Julian of Norwich, a woman, Juliana, she said “It beholdeth that there be sin.” It could not be otherwise. Sometimes people ask, “Why didn’t God make a world in which there would be no sin?” And it seems that the bold answer we must make is because there is no such world, there are no creatures, there are no human beings who do not sin.

And that’s very important to remember, because that’s what allows us to identify with Adam in the Church hymns. We can’t say, “Oh, here I am because someone else has sinned; I would never do that.” That is simply not true; it’s simply the truth that if we ourselves were the original humanity, the original human beings, we would have sinned as well. How do we know that? Well, the saints tell us we know that by a very simple reason. We know Christ and the Gospel and we still sin. And St. Simeon the New Theologian said, commenting on this, he said, “Our sin is worse than Adam’s. He was some kind of primitive earth creature, raised from the dust, tempted by the devil, trying to learn how to be a human being. And he sinned from the beginning, and God knew that he would do it. But look at us; look at us,” he said.

He ate that fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which simply symbolizes that he sinned. He existentially tasted of sin; he did it whatever that “it” was—and we don’t know what the original sin specifically was—we do know that it was rebellion, we do know that it was not trusting God, we do know that it was not believing, we do know that it was disobeying—but it’s in that sense a paradigm of all sin. One thing we know for sure it was not sexual. It wasn’t that, I don’t know, Adam and Eve had sex or something; that’s absolutely not the teaching. They were commanded to increase and multiply in Paradise. But we have no record of that in fact, we have no record of an unfallen life at all, in the story of Genesis and the Genesis narratives, none whatsoever. We don’t know a thing about Adam and Eve “living before they sinned.” We could know they were created for totally beautiful glorious life with God in Paradise, and that their task was even to spread Paradise to the whole chaos outside Eden.

Some Fathers even think that that’s humanity’s vocation to break the presence and the Paradise of God to the chaos where it does not exist. Because there was an outside Paradise, and the Paradise in the story is a little place, and Adam and Eve were supposed to increase and multiply and develop and deify creation. But instead they didn’t; they fell, they rebelled, and found themselves cast out weeping. But we know that if we were with them, we would have done the same, because we sin anyway. St. Simeon says, “They ate of that tree of the knowledge of good and evil, but we eat of the body and the blood of Christ at the holy Eucharist.” And he says, “When the body and blood of Christ is still in our mouth, we leave the church and we sin. It’s like the people of Israel, who were led out of Egypt and fed by manna, and while the manna of God was in their mouth, they blasphemed and worshiped the idols and did wickedness. So no human being gets off the hook; no human being can blame anyone else. Each one of us stands on our feet. However it is true that we are not Adam and Eve and we are already, as it says in the psalms, “conceived in iniquities; in sins our mother conceived us,” not that the act of conception is a sin, but that we’re born into a world already broken, already apostasized, already rebellious.

If you put it in the other symbols of the season, you could say: we’re born in Babylon; we are not born in Jerusalem. We’re born in the pig pen; we’re not born in the father’s house. We have to be taken back to Jerusalem, taken back to the father’s house, taken back to Paradise. And we believe that that’s what Jesus had done for us, and that’s we are celebrating during Lent and Holy Week and especially the Holy Pascha. We are celebrating the fact that God sent his son to be the real final last Adam who does not sin. We are celebrating the fact that he has searched us out and found us: in the pig pen, in the far country, outside Paradise. And he forgives us and he cleanses us and he washes us and he refreshes us and renews us and restores us and resurrects us from the dead and takes us home to the house of the father, takes us home to the heavenly Jerusalem, takes us home to the paradise on high.

So during the Great Lent we begin the whole season by remembering our exile, remembering our status, remembering who and what we are and how we are and where we are, cursed, sinful, dead by our own doing, as the human race, as a whole and as individual human beings and there is no one who lives who does not sin, there is no one who is righteous; none at all except the Lord Jesus Christ himself. He is the sinless one who became in all ways as we are. As it says in the letter to the Hebrews, from which all the epistle readings during Lent will be taken, in that letter to the Hebrews he said, “He became like his brothers in all respects, in order that, by becoming like us, we might become like him. He was tempted as we are tempted in order to be with us who have fallen into temptation.”

So on the Sunday, the very eve of Great Lent, these are the things that we remember. This is how we identify ourselves, this how we see ourselves. But we see ourselves not only banished, cast out, expelled, sitting outside Eden, weeping, but we see ourselves also as the objects of the infinite mercy of God, that he, knowing this, knowing it, began at all from the beginning, knowing that the Son of God, the eternal divine logos and word of God, God’s own son, God’s own image would not cling to his divinity, as St. Paul said in the Philippian letter, but would become human, become found in the form of man, and not only human, but dead, cursed, hanging on the tree of the cross taking on himself the whole condition of fallen humanity in order to make us divine.

So we begin the great Lenten season meditating upon these things.

Source: Ancient Faith Radio