“Can we all clearly picture the kind of responsibility we are taking upon ourselves? Unfortunately, for some among us this moving rite often takes on the tint of a formal performance of mutual forgiveness.” – Archimandrite John (Krestiankin).

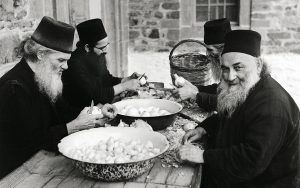

The tradition of asking forgiveness on the last Sunday before Great Lent dates back to ancient Egyptian monasticism. Their life was not an easy one: when departing into the desert for the entire forty days of the fast none was certain that they would return from their solitude. Therefore they would ask forgiveness of one another, as before death, just before leaving.

Do we know what true, profound forgiveness is? How it differs from reconciliation? How to prepare for Forgiveness Sunday and for the Church’s Rite of Forgiveness in such a way as not to reduce it to a formality? Priest Andrei Lorgus, Rector of the Institute of Christian Psychology, responds to these questions.

Reconciliation and forgiveness are two different things.

Reconciliation and forgiveness are two different things.

Reconciliation can be achieved through various means, including through material means. I can cause damage to another person and can subsequently reconcile with him through some action of a sacrificial nature: I can give him money or provide him with some service in order to achieve reconciliation. But this will be neither forgiveness nor repentance.

All the same, the Church has foremost in mind not reconciliation, but forgiveness: moreover not so much receiving forgiveness, as asking for it. On Forgiveness Sunday it is much more important to offer repentance to another – to say, “Forgive me!” – than it is to receive forgiveness.

I think that the ancient tradition of asking forgiveness of one another before Great Lent implied primarily this half, this part: not reconciliation, not receiving forgiveness, but namely asking for forgiveness. Of course, this asking combined both personal repentance and asking something of someone, while the important thing was not so much asking forgiveness of him so much as reconciling with him in one’s soul. Even if this person is very unpleasant, even if this person wishes me harm, even if this person is ready to manipulate and laugh at me… I need this!

Asking forgiveness of him and becoming internally reconciled: I need this; this is my spiritual exercise; this is the beginning of my Lenten repentance.

Yet very often people think that if I ask forgiveness of someone I will still owe him something: that after this I must become his friend, I must become close to him, I must become family to him. But this is dangerous. What if he begins again to laugh at me, to mock me, to humiliate me? One must bear in mind that asking forgiveness, reconciling with him in one’s soul, by no means implies communicating with him later, because the decision to reconcile internally does not correspond to the decision to carry on some sort of close relationship with him later.

I can ask forgiveness, all the while deciding for myself that I will no longer have anything to do with this person, because he is dangerous and wants to mock me – or simply because I no longer see any prospect of communication. This is my decision and my responsibility. Therefore forgiveness by no means requires that one become close to this person.

But if this is a loved one – and, as a rule, we sin above all against our loved ones and relatives – then there can be no question of a split or an estrangement. There is nowhere to go. All the same, family is family.

This, of course, requires an internal commitment not only to ask forgiveness, but also to become reconciled, to restore one’s love for him in one’s soul and to draw nearer to one’s own love, since it is still there. When it comes to loved ones, then we already love them, which means that we must somehow purify that love, somehow draw closer to it, somehow find new means by which to live with this person. This, I think, is the most important thing.

What if something thinks: “Well, I suppose I’ve forgiven him in my soul,” but decides not to say a word about wanting to be reconciled. How correct is this? How far removed is this from a real achievement?

This, of course, is the avoidance of any real achievement and the avoidance of real life. It is as if I saw a very tasty dish on the table and ate it in my soul. In reality I would remain hungry. It is exactly the same thing here.

What should one do if we do not feel ourselves guilty, but a loved one makes us ask forgiveness by manipulating us and calling into question our future relationship?

Makes us? No, this is impossible. The decision to forgive and be reconciled with this person is born in the heart; no one can force me to do this.

It might be another story if there are special circumstances, if for legal reasons one needs to offer repentance to someone or to seek reconciliation through the newspaper. But that is another story. Do understand that this is not forgiveness.

There can be no sincere forgiveness where there is manipulation; before Lent we are talking about sincere forgiveness and sincere inner reconciliation, because all of Great Lent, strictly speaking, exists for this reason.

Great Lent is not about formal things, but about internal things; it is only for oneself.

Incidentally, the tradition of a general Rite of Forgiveness is very difficult in this sense, because it is one thing to ask forgiveness of one’s loved ones, and quite another thing to ask forgiveness of everyone in church. At least 80% of the people in church have never had anything to do with me. In this case I ask forgiveness of them formally, but this is only a formal rite. This is precisely what makes it a temptation for many people, since it seems like a formality.

This is also a temptation for priests, by the way, since people from different parishes, from different regions of Moscow and even different cities, suddenly show up and also ask forgiveness, although this may be the only time in our lives that we will meet. This, of course, has a symbolic meaning, but none, of course, in a literal or substantial sense. The Rite of Forgiveness exists for entirely different ends. These are different things.

The general Rite of Forgiveness has, of course, a formal character. The church is open to everyone, our parish does not have clearly defined boundaries, parishioners do not belong to only one parish, and therefore all kinds of different people might turn up for the Rite of Forgiveness. And, conversely, it could happen that those who would be very important to me might not be there.

Therefore, when we celebrate the Rite of Forgiveness we offer the possibility for anyone to participate in it openly. Each person can independently determine the inner significance of this event for himself. He can then take the rite into the heart of his home, calling loved ones or asking forgiveness of them at home.

But this does not relieve anyone of the necessity of performing this Rite of Forgiveness for oneself not just formally, but substantially, essentially, and fundamentally. This means that one has to prepare for it. This means that one needs to think ahead of time about with whom one needs to be reconciled and of whom one should ask forgiveness. Of course, while one is preparing one needs to place first and foremost the weightiest transgressions one has done to someone, the most difficult relationships, and then go in descending order. This is what requires the most amount of effort.

Generally speaking, the main part of forgiveness is preparation: deciding that “yes, I want to be reconciled to this person, to repent before him, to ask forgiveness.” Second, there is the feeling from which this decision is born: this is the feeling of repentance, the desire for reconciliation, the desire to ask forgiveness.

It is this inner desire, when it arises, which offers hope that the Rite of Forgiveness will be meaningful and substantial.

Translated from Russian.