Despite the significance of pilgrimage to Jerusalem, not all Popes and Patriarchs have visited the Holy City. Historically, pilgrimage was largely connected to catechesis and missionary work, so not many bishops in the olden times thought it necessary to participate in it, leaving their dioceses. After all, if you prayed well, you could have “both Athos and the Holy Land” in your cell. Primates of the Churches usually came to Jerusalem on very special occasions.

Sometimes it was for the consecration of important churches. Thus, St. Cyril – one of the Fathers of the Church and a Pope of Alexandria – was in Jerusalem in 438 (439) for the consecration of the new basilica in honor of the Protomartyr Stephen. Others came for Councils of Bishops, gathering bishops of various local Churches. Thus, the Council of Jerusalem of 1443, which was attended by all the Eastern Orthodox Patriarchs or their representatives, was one of the most important stages in the rejection of the Union of Florence.

This applies to heads of the Russian Church. The visit to the Holy Land in 1924 of Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky), First Hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad, was undertaken to “rescue” the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem and to determine its status in the new conditions of emigration. The first visit to the Holy Land of Patriarch Alexy I of Moscow took place in 1945, marking a new stage in the life of the Church in the Soviet Union, as well as the entry of the Moscow Patriarchate into the “international arena.” The last visit of Patriarch Kirill was connected with the consecration of a large cathedral in honor of All Saints of Russia in Jerusalem.

Not all Patriarchs of Constantinople visited Jerusalem, either, although in the twentieth century the simplification of methods of transportation made possible the visits of neighboring Churches without having to leave them for a long time. One of the most notable visits was the pilgrimage of the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras to Jerusalem in 1964. On this occasion he coordinated his visit to the Holy Land with that of Pope Paul VI of Rome.

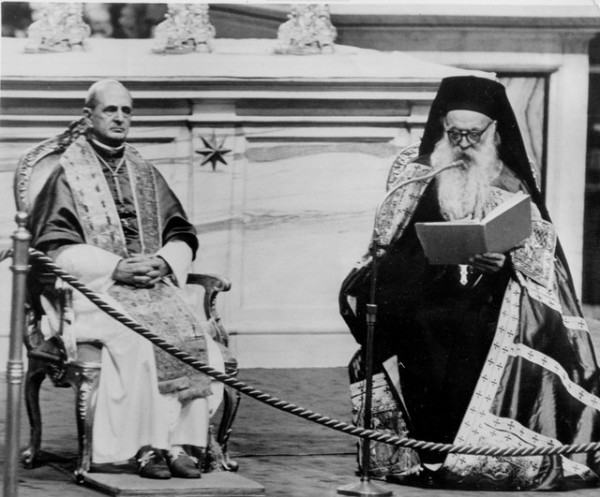

The meeting of the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI of Rome in Jerusalem in January 1964 was the first meeting of a Pope and an Orthodox Patriarch after several centuries without personal meetings, following the tragic Council of Florence in 1439; they did not meet for several centuries.

The historical meeting took place on January 5, 1964, in the house of the Papal Nuncio in East Jerusalem, at the foot of the Mount of Olives. It was then Jordan: Jerusalem was united in 1967. The meeting marked the beginning of the “dialogue of love,” as Patriarch Athenagoras then called it.

The practical implications of this (and following meetings) were significant. The head of St. Andrew the Apostle was returned to Patras. The relics of St. Sabbas the Sanctified were returned from Venice to his monastery in the Judean desert… But most important, in December 1965 the anathemas were lifted that had been mutually imposed on the Church of Rome and Constantinople in 1054. This was done simultaneously in Rome and Constantinople. “We decided to confine to oblivion,” reads the document of the Constantinopolitan Synod of December 7, 1965, “and erase from the memory of the Church the above-mentioned anathema pronounced by Patriarch Michael Cerularius of Constantinople and the Synod headed by him. So, we declare in writing that this anathema, pronounced in the year of our Lord 1054, in the month of June, in the seventh indiction by the Great Office of our Great Church, is now and forever consigned to oblivion and obliterated from the memory of the Church.”

Did the Constantinopolitan Church have the right to rescind the anathema of the eleventh century? Yes, inasmuch as it was they who imposed it. Whether the anathema of Patriarch Michael Cerularius was justified is a separate issue. But the Church has the right not only to “bind,” but also to “release.” The Church and its archpastors today have the same rights to make decisions as they did in ancient times. In the canonical sense, this event is similar to the removal of the “oaths” with the Old Believers, which was undertaken both by the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Church Abroad in the same years.

Does the lifting of anathemas (“oaths”) mean the full restoration of unity? No. Rather, it can sooner be compared with the reconciliation of spouses who have long since parted ways, than with the restoration of their family life. This should not be confused, just as it should not detract from the reconciliation.

Patriarch Athenagoras considered the “Dialogue of Love” to be an essential theological dialogue. In the Orthodox Church, a common Eucharist has always been the sign of ecclesial unity. Patriarch Athenagoras repeatedly stated that Communion from a single chalice – that is, the restoration of unity – is the goal of the dialogue between the Orthodox and Catholics. However, contrary to popular belief, neither Patriarch Athenagoras, nor his successors, nor bishops of the Russian Archdiocese of the Ecumenical Patriarchate have ever served a common Liturgy with the Pope or Catholic clergy. Moreover, the decision of the Moscow Synod of 1969 (suspended in 1986) of allowing Catholics and Old Believers to Communion in Orthodox churches in cases of necessity met with criticism from the side of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Why? Because the “Dialogue of Love,” the theological dialogue and cooperation between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, has not yet reached full unity.

After the Jerusalem meeting in 1964, the dialogue between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches has undergone many stages. There have been many “ups” and “downs.” However, communication between bishops, clergy, and laity of both denominations, which was earlier “objectionable,” has now become an everyday reality. Sometimes it seems that the theological dialogue has gone by the wayside but, on the other hand, the Catholic Church now considers its “new dogmas” to be theologumena and the faith of the “Church of the Seven Ecumenical Councils” to be the general guideline.

The current pilgrimage, of both Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and Pope Francis, is dedicated to the fiftieth anniversary of the 1964 meeting. The Primates of the two Churches are coming independently of one another, and are having separate pilgrimages, but are meeting at the Lord’s Sepulcher, in memory of the meeting of their predecessors at the foot of the Mount of Olives in 1964.

The Pope’s pilgrimage is primarily associated with visiting the Arab countries of the region. It begins in Jordan. Then the Pope, bypassing Israel, will fly to the “Palestinian state,” as it appears on the official program, and visit Bethlehem. Although Bethlehem is separated from Jerusalem by only a small ravine, and pilgrims usually move from Bethlehem to Jerusalem in ten minutes through one of the checkpoints of the future border, the Pope will fly from Bethlehem by helicopter to Tel-Aviv, to the “Ben Gurion International Airport.” In the Tel-Aviv airport will take place the official meeting of the Pope in Israel, and from there he will fly by helicopter to Jerusalem. A large Mass will also not take place in the Kidron Valley in Jerusalem, as before, but in a stadium in Amman and in the Bethlehem basilica.

Why does the pilgrimage begin in Amman? Perhaps there is a remembrance here that, before the unification of Jerusalem in 1967, most of the pilgrims visiting the Holy Land as part of Jordan, not Israel, and first came to Amman: the main shrines were then on Jordanian territory. Visiting the “Palestinian state” undoubtedly has a political aspect: the Catholic Church de facto recognizes it before the rest of the world. And the visit to Israel will begin not in Jerusalem, which is two steps away, but from the Tel Aviv airport. Might such a policy “appease” the Muslim world and mitigate the situation of Christians in Arab countries? In the Palestinian Authority itself (as it is still officially called), Christians make up less than one percent…

In Israel, the Pope will visit only Jerusalem. And here everything will take place not in stadiums, but in fact “behind closed doors.” Largely to blame is the “democracy” of Pope Francis: he refuses to ride in an armored car. But, as a result, all the approaches to the places of the Pope’s residence will be closed by police for several hours before the arrival of the head of the Catholic Church: the safety of the Pope in Israel will be monitored by several thousand police officers.

The most difficult point of the Papal program will be his visit to Mount Zion on Monday evening, May 26. Instead of a Mass, as with John-Paul and Benedict, Pope Francis will serve on Monday on Mount Zion with very few participants. During the Mass there will be two helicopters on Zion and snipers on the roof of the surrounding buildings. Representatives of radical Jewish organizations will be banned during the Papal visit (almost like during Roman times). The problem is that the top of Mount Zion is de facto divided between Catholics and Jews.

The status quo was broken long ago on Zion, and each side expects nothing good from the other. In such a situation, a Papal Mass in this place can hardly be considered a politically neutral event.

The Liturgy that will be headed by Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and Patriarch Theophilos of Jerusalem will take place in locations whose ownership by the Orthodox in unquestioned: in the main chapel of the Church of the Resurrection on Saturday and the Catholicon of the Church of the Resurrection (the Holy Sepulcher) on Sunday morning. The major companions of the Ecumenical Patriarchate will be several hundred Greek pilgrims from North America (they are the main sponsors of the Patriarchal pilgrimage) and a series of bishops. First among them will be those who are perceived as the “European faces” of the Ecumenical Patriarchate: Metropolitan John (Zizoulas) of Pergamon, who at one time was a deacon of Patriarch Athenagoras; Archbishop Demetrios of America, Metropolitan Emmanuel of Gaul, and the recently elected Archbishop Job, the head of the Russian Archdiocese of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Western Europe, Rector of the St. Sergius Theological Institute in Paris.

The visit of the Ecumenical Patriarch to Israel and the Palestinian territory is not political. At least, it is not a state visit, unlike that of the Pope, who is still the head of a government. At the same time, Patriarch Bartholomew will meet with the Israeli Prime Minister and the President of the Palestinian Authority.

But the main thing remains the visit with Pope Francis. Besides the more closed and private meetings, there was the official main meeting at the Holy Sepulcher on Sunday evening, which was attended by not only the Orthodox and Catholic delegation and representatives of other faiths represented in Jerusalem. The first talk was given by Patriarch Theophilos, followed by Patriarch Bartholomew, and following him, the Pope. The Patriarch spoke in English, and the Pope in Italian. Then they read the Our Father together and went to the Edicule for silent prayer. Before this meeting, which was televised on many stations, the Patriarch and Pope signed a joint declaration.

“Our fraternal encounter today is a new and necessary step on the journey towards the unity to which only the Holy Spirit can lead us, that of communion in legitimate diversity…

“While fully aware of not having reached the goal of full communion, today we confirm our commitment to continue walking together towards the unity for which Christ our Lord prayed to the Father so ‘that all may be one’ (Jn 17:21).

From the side it is sometimes unclear why the Ecumenical Patriarch has made so much effort for dialogue specifically with Rome. Is his “Eastern Papism” the reason? For the Russian Church, division with the Catholics has been a fact almost from the beginning of its existence. But for the Byzantines, and later the Greeks, the memory has been preserved of Rome as the main fraternal see from which the New Rome – Constantinople – takes its name. It has preserved memory of unity; it has preserved memory of the division that was “fixed” not abstractly between the Eastern and Western Churches, but concretely between the sees of Rome and Constantinople. The search for unity is a search for the healing of old wounds and the restoration of a unity that has never been forgotten. Just as for the Russian Church, the division with the Old Believers is not abstract, but real; just as in Ukraine the division with the Greek Catholics and many subsequent schisms are very real.

The head of the Catholic Church and the preeminent Orthodox Patriarch in Jerusalem have not said anything new, but they have inspired us to seek the lost unity where it was once broken, and not without our participation.

Translated from the Russian