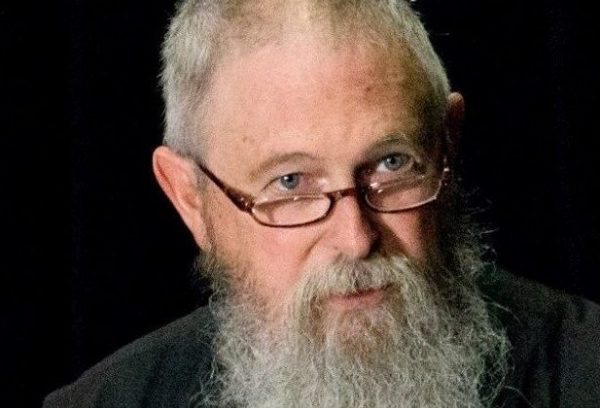

A couple of years back, a comment was posted on social media that described my writing as consisting of “existential despair” and “moral futility.” It was not meant with kindness. However, after I reflected for a while, I realized that it was not only accurate but quite insightful. It also made me say, “I have become Dostoevsky!” This tenor in my work does not come from careful planning or systematic thought – it largely grows out of my experience and reflection on the Orthodox life.

Existential Despair

Our life is fragile and exists only as a precious gift. We have no existence in-and-of-ourselves and are thus utterly and completely contingent beings. This rather obvious conclusion has been frequently reinforced over the course of my life and ministry. I have buried hundreds of people. Death is a fact of life. However, our culture maintains a pretense and delusion of self-existence, even imagining that we somehow invent ourselves. It is a good marketing strategy as we sell mounds of trash for people to use in their efforts of self-definition.

I do not despair of life and existence itself, except in the sense that it is anything other than pure gift. As such, to stand at the edge of the abyss of non-existence seems to me to be among the sanest efforts ever undertaken. We cannot possibly understand who and what we are until we also consider the fact of our death.

God is the “Lord and Giver of Life,” and not just the “Lord and Giver of Life after Death.” Those who struggle to believe that there might be such a thing as life after death have failed to ponder just how absurdly improbable life before death truly is. Our existence shouts the reality of a Giver of Life – all life. Our non-existence proclaims the emptiness of any claims to the contrary. I hope in God. In Him, there is no despair. But only in Him.

Moral Futility

I caught a lot of flack some years back for an article entitled, “The Unmoral Christian.” It suggested that we make very little progress of the moral sort in our lives. The track of salvation is not, by and large, one of moral improvement. I understood at the time why there was so much push-back: it was assumed by many that I did not think moral improvement to be possible or even desirable. That is not the case.

The moral life, if rightly understood, cannot be measured by outward actions. The Pharisees in the New Testament were morally pure, in an outward sense, but, inwardly, were “full of dead men’s bones.” When morality is measured by dead bones, it is still nothing more than death. However, the path that marks the authentic Christian life should be nothing less than “new life,” a “new creation.” This is a work of grace that is the result of Christ “working within us to will and to do of His good pleasure” (Phil. 2:13).

This is not something that takes place within a life of passivity. However, neither is it a sort of divine exo-skeleton making our efforts more powerful. The “synergy” taught by the Church is one in which we work rightly within our proper sphere, doing what is humanly possible. Human effort cannot make what is dead to live: only God can do such a thing. Repentance is the primary effort of our life.

The Elder Sophrony once described this by saying, “The way up is the way down.” The spiritual life is a paradox. The excellence of the Pharisees was met with condemnation from Christ: they could not see their own emptiness. The emptiness of the weak and “sinful” was met with mercy and healing. Their acknowledged weakness made the working of the power of God effective in their lives.

What passes for a “moral life” in our culture, is little more than the successful internalization of middle-class behavior. “I’m doing ok,” we think. It is quite common for those who are “doing ok,” to feel generally secure and superior to those who fail to do so. In earlier modern centuries, this modest morality was sufficient to earn someone the title of “Christian.” It meant nothing more than being a gentleman.

It is necessary, I think, to see the emptiness of our efforts (moral futility). Just as we cannot make ourselves to live, neither do we make ourselves better persons. An improved corpse is still a corpse. Our repentance is born out of the revelation of our emptiness and the futility of life apart from God. St. Gregory of Nyssa once said, “Man is mud that has been commanded to become a god.” It is the impossibility of that task that allows the heart to cry, “Have mercy on me!”

It is for this same reason that the lives of saints are never marked by a saint’s awareness of his improvement. Like St. Paul, the authentic witness of the saints is their self-perception as the greatest of sinners.

Of course, existential despair and moral futility are not my self-description. They are terms chosen by a detractor. I believe that mud not only can become a god, but that it has – many times. This is the work of God who hears our cries and works within us, doing what He alone can do, just as He alone gives us the life we live and breathe at every moment. It is not despair because every moment of our present gifted existence shouts and proclaims the goodness of God, the author of being. It is not futility because with God, all things are possible.

But apart from Him, we can do nothing. That “nothing” is indeed despair and futility.