An unusual exhibition has opened at the Zurab Tsereteli Art Gallery in Moscow: “Folk Icons,” at which items from both museum and private collections are on display. Folk iconography, not always observant of the canons of either church or secular painting, is candid and enigmatic. Correspondents from PRAVMIR visited the opening.

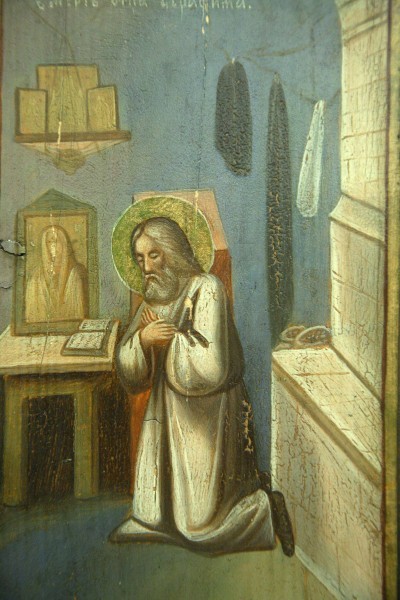

I remember visiting someone’s house while still a child and standing for a long time before the kitchen’s icon corner. There were mainly icon prints glued onto wood: Rublev’s Trinity, the Vladimir Icon, St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, St. Seraphim of Sarov. But it was not these that attracted me.

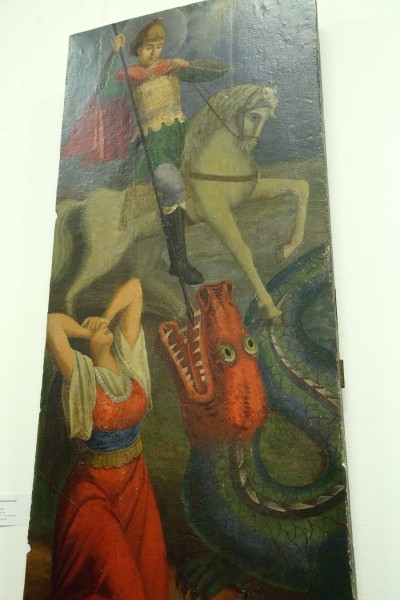

All of my childish attention was directed to an image of St. George the Trophy-Bearer, warped with time. It was hand-painted, as I now recall, and fairly hopeless in its artistic execution: the horse under St. George was the size of a dog, so it was unclear where it got the strength to carry a rider in heavy military accouterments. The serpent (which, as we recall, devoured people) looked very much like a miserable worm, the defeat of which would not have required the trouble of putting on armor and wielding a spear: stepping on it with his boot would have been quite enough.

Yet despite this hopelessness (or, perhaps, because of it), this icon seized my undivided attention, as if it were not a board, but rather a window looking from the present into the past.

Our host, noticing my curiosity, took down the icon from the shelf and gave it to me to hold. For a long time I ran my hand over the blisters of paint, turning the icon over, and sniffing it. Its smell struck me as that of time itself…

I vividly remembered all this on June 19 at the Zurab Tsereteli Art Gallery on Prechistenka Street in Moscow, where the “Folk Icon” exhibition opened.

The exhibition is unique not only in that it reveals a layer of popular culture that is mysterious and little studied, but also in that this layer has never before been represented in any single exposition of this size: around 400 items from more than thirty private and museum collections are in the halls of the gallery. Among the museums represented are: the State Research Institute for Restoration, the Yaroslavl Architectural Historical Museum Preserve, and the Museum of Church Archeology at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University; among the collectors of Russian art are Yevgeny Roizman, Aleksandr Ilyin, Vyacheslav Momot, Mikhail Chernov, and many others. The geography of the items on display stretches from Siberia to Estonia.

This begs the question: why has this project become possible only now? It seems that every idea is realized only when a certain critical mass has been reached. Yevgeny Roizman, a collector from Yekaterinburg who submitted around 150 items to the exhibition from his personal collection, said that at one time the common attitude towards folk icons was that they were cultural “dross,” too far removed from the strict ecclesiastical canon to have status as sacred objects and too far removed from the canons of painting to be considered works of secular art. There were even cases of their mass destruction.

Today the time is finally ripe for us to look at folk icons impartially and for them to take their rightful place in our culture. As evidence of this are two exhibitions of folk icons that took place last year: one in the Kirillo-Belozerski State Historical Architectural Art Museum-Reserve and the other in the museum complex of the village of Vyatka in the Yaroslavl Oblast. Both exhibitions generated enormous interest among both the general public and specialists.

So what are folk icons?

Mikhail Alekseevich Chernov, director of the icon section of the journal Antikvariat [“Antiquarian”] and one of the coordinators of the exhibition, highlights two main characteristics of this “genre.” The first is that these icons are painted by amateur, unsophisticated artists for equally unsophisticated patrons. The second is that they are craft icons “replicated” for wide use (something like today’s icon-calendars, only handmade). Entire iconographic villages and settlements existed, among which were Kholui and Palekh (Pavel Korin, the painter and icon collector, was from the latter).

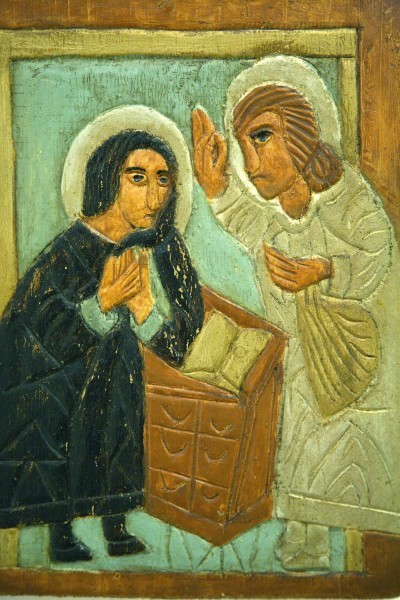

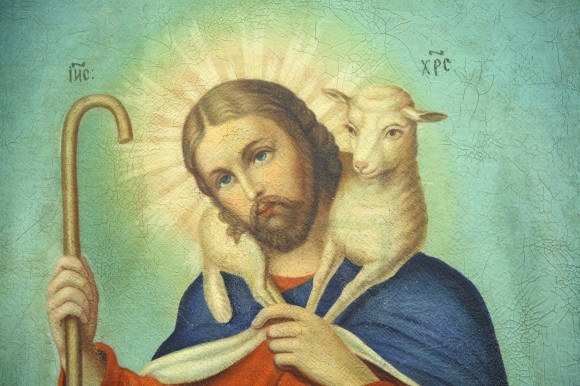

When discussing the works of Dionysius, Theophan the Greek, or Andrei Rublev, we speak primarily of spirituality [dukhovnost’]; folk icons are characterized by no lesser degree of warm-heartedness [dushevnost’]. In folk icons the personalities of the authors are distinctly palpable: they are craftsmen, amateurs, enthusiasts, dreamers; they are tangible, seeking and striving towards God. “Touching,” “naïve,” “childlike,” “adorable” – such were the descriptions one heard most often from guests at the opening.

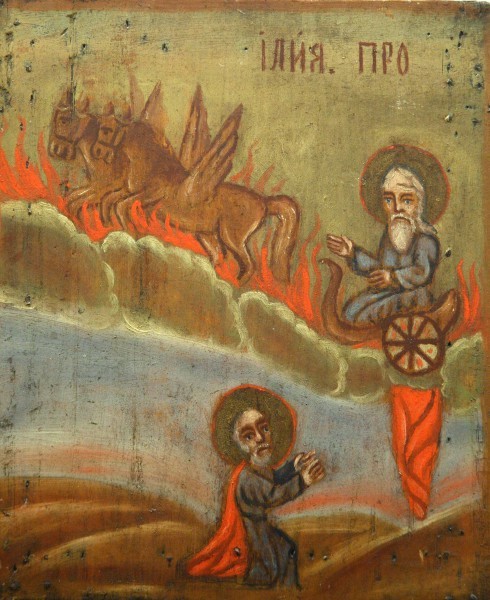

Here we see the same St. George the Trophy-Bearer in several variations: some like the one I saw in childhood, with the “serpent-worm”; some more “serious,” apparently painted with some canonical model in mind; and finally, “full-fledged” images of the hero, with an entire genre painting including the princess, her hands covering her face in terror, and the serpent, already inducing a bit of fear, reminiscent of the formidable Gorynych dragon of folktales.

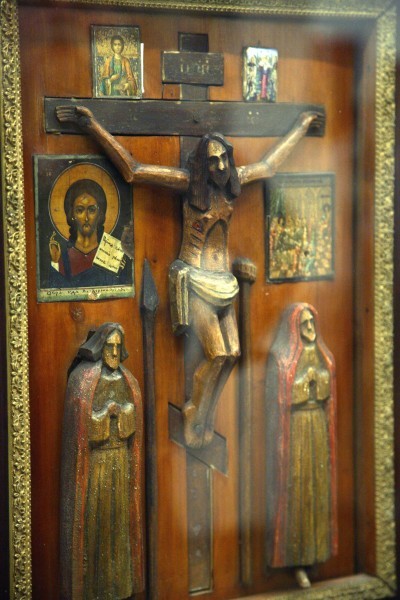

We see “foil-covered” [podfolezhnitsa] icons. On these, only the faces are painted; the surface of the icon is then covered with foil, onto which embossed figures and halos are etched. These cheap covers looked fairly rich and “respectable,” which of course pleased the eye of Russian commoners in their homes and rural churches.

And here is the wise thief, Rach [folk name for Dismas – Tr.], who came to believe in Jesus on the cross. He has a disproportionately large head and humongous, childlike eyes of unbelievably penetrating force. There is a mysterious detail: the thief has two right legs. Perhaps this is a blunder of the seventeenth-century “icon-dauber,” or perhaps it hints at this thief being at Christ’s right hand in the Kingdom of God…

Here we also see wooden sculpture, enamel, and metal (copper) icons – everything you can imagine; one could spend the whole day in the gallery’s exhibit halls.

The authorship of the majority of items has not been established. This is common practice for iconography. The annotations to the icons are laconic: name, century, and place of origin, often only approximate: the Russian North or South (the latter are easily identified by the bright flower buds interspaced within the depictions). Lost in this abyss of time and space are the identities of the authors: diligent, sincerely believing people who left a good mark on this earth through their art.

Dr. Irina Leonidovna Buceva-Davydova, the curator and director of the project, was asked: “Who were these people, these folk iconographers? Did they pray fervently and fast strictly in approaching their work, as did their professional colleagues?”

Responding to this question, Irina Leonidovna recalled a fragment from the life of the iconographer Dionysius. Observing the strictest fast while working, he once fell into temptation: he bought a leg of lamb stuffed with eggs. Anyone can fall into temptation, and therefore there is no point looking down on folk artists, belittling them before the recognized masters. It goes without saying that folk iconographers also felt their responsibility before God for their work and strove towards piety.

But icons are not simply paintings that reveal their authors’ inner world and the historical and social context of their lives. Icons are prayerful images intended to unite us with their prototype. The organizers of the exhibition removed them from their sacred context: not a single priest or historian of church art was present at the exhibit, although some had been invited. A theological evaluation of folk icons was not only not given, but the very question of their conformity to the canons, and of the specific character of “folk theology,” was not raised.

The organizers of the exhibition were the Russian Academy of Arts, the Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts, the Ferapontov Society for the Preservation and Study of Monuments of Russian Culture, and the journal Antikvariat.

The exhibition runs until September 16, 2012.

Text: Yuri Lunin; photography: Xenia Pronina.

Translated from the Russian