So this man pulls up to church just as I did the other day. He got out of his car and asked, “Is this the Episcopal Church?” I said that it was their chapel but that we rent it for our services. Without noticing our white signboard he said, “Well, what’s your church?” and I responded, “We’re the Orthodox Church in Las Cruces.” He asked what that meant, with a puzzled look on his face, and I said, “We are global but sometimes we are known as the Eastern Orthodox Church,” and then he said, “Oh you mean GREEK or RUSSIAN Orthodox.” I could hear the capital letters in his voice. His reaction made me think once again about this problem.

What happens when some other tag identifies you than the one you want people to know?

We Orthodox Christians often say things like, “we’re the oldest Christian church, we were there from the beginning, and long before the split with Catholicism,” but in America that and $2.00 may buy you a cup of coffee. It’s true, of course, but history and antiquity mean nothing in America except to a small number of people – like those who love classical music. To be identified by an ethnic tag signals that you may cater to a limited group.

At St Anthony of the Desert, we put no ethnic identification on our sign. Who needs even more trouble in a part of our country where Orthodoxy is almost totally unknown? Our problem is more basic: we’re not even recognized as church. So these ethnic identifications only hinder us further. We don’t need the extra hassle.

It wasn’t always that way. Orthodoxy began in America via the Russian church, with the idea to build up the church in America to the point where it could become self-sufficient as one Orthodox Church in America. Unfortunately, that’s not how it turned out – due in large part to the ruination in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution and the onset of the Communist period. But we live with the consequences of history good and bad. Orthodoxy has suffered a lot of bad consequences over the last 800 years.

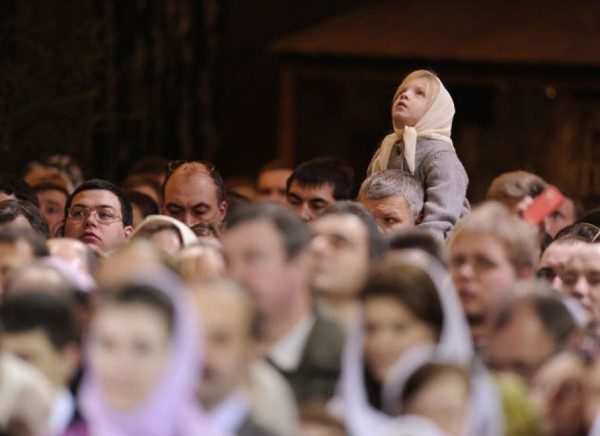

Orthodoxy has never been limited to ethnic boundaries. We are on record as declaring such a limitation to be an affront to the faith and, in fact, a heresy. The church is for people of all backgrounds; that was part of its genius in the early centuries. Fear of strangers was replaced by love of strangers as people from all sorts of backgrounds and ethnicities became one in Christ.

Any church can turn into an ethnic enclave. When I was growing up in Philadelphia, a “mixed marriage” was when an Irish Catholic married an Italian Catholic. In America this ethnic business may be much more subtle than blatantly identifying with only Germans or Russians; it can be identifying with folks of a certain mentality or political persuasion. We might call that tribalism.

It’s not ethnicity that separates people, in this case, but when you stick in any other qualifier, you abandon the Christian ideal. Some churches have become so identified with right wing or left-wing political causes that almost no one who holds a contrary position would set foot in them. When you narrow the scope from the central purpose of the church to proclaim the Gospel of Christ, you are going to lose. Period. No qualifier must come before the faith.