The Elder’s Love.

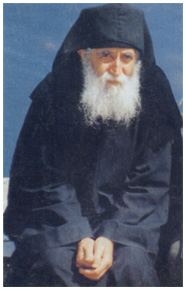

In the words of H. Middleton, author of the recently published Precious Vessels of the Holy Spirit, Elder Paisios of Mount Athos, “perhaps more than any other contemporary elder, has captured the minds and hearts of Greek people” (H. Middleton, Precious Vessels of the Holy Spirit: The Lives and Counsels of Contemporary Elders of Greece, Thessalonica, Greece: Protecting Veil Press, 2003, p. 129). Although not nearly as well known in the English-speaking world as in his homeland, this holy Elder also has much to say to contemporary spiritual seekers in the West. In his life and teachings, we can find a key by which to go deeper into the heart of the Orthodox Christian Faith.

In the words of H. Middleton, author of the recently published Precious Vessels of the Holy Spirit, Elder Paisios of Mount Athos, “perhaps more than any other contemporary elder, has captured the minds and hearts of Greek people” (H. Middleton, Precious Vessels of the Holy Spirit: The Lives and Counsels of Contemporary Elders of Greece, Thessalonica, Greece: Protecting Veil Press, 2003, p. 129). Although not nearly as well known in the English-speaking world as in his homeland, this holy Elder also has much to say to contemporary spiritual seekers in the West. In his life and teachings, we can find a key by which to go deeper into the heart of the Orthodox Christian Faith.

As books published after his repose indicate, Elder Paisios was a man of lofty spiritual life. He received many heavenly visitations from our Lord Jesus Christ, His Most Holy Mother, and the saints; he was granted the gifts of clairvoyance and of miracle-working; he beheld the Uncreated Light in divine vision; and he was filled with God’s Grace to such an extent that he attained to deification (theosis).

There is no doubt that Elder Paisios’ impressive spiritual gifts and attainments have contributed to the widespread veneration of his memory in contemporary Greece. However, these gifts are not the only — or even the primary — reason he has come to be so greatly loved. For the main explanation as to why he is so loved by the people, we must look at the love which he had for the people. That love, borne aloft by the Grace of Christ, was seemingly limitless.

Elder Paisios poured out his heart in love for his fellow man. As his spiritual children have written, “His sanctified soul overflowed with divine love, and his face radiated Divine Grace” (Elder Paisios of Mount Athos, Epistles, Souroti, Thessalonica, Greece: Holy Monastery of the Evangelist John the Theologian, 2002, p. 10). He suffered with people, listened to them, offered them hope, and prayed for them untiringly. He spent his nights in prayer and his entire days in relieving human pain and spreading divine consolation. He guided, consoled, healed, and gave rest to countless people who took shelter in him.

In his spiritual counsels, many of which have been recorded in writing, Elder Paisios tells us how we too can enter into the experience of such overflowing, Grace-filled love. The path he sets for us is indeed a hard and narrow one, for it is none other than the path that Christ has given us.

On Pain of Heart.

First of all, Elder Paisios tells us that, for love to blossom in the heart, we must pray with pain of heart. Once he was asked, “We pray, Elder, and our thoughts go here and there. Why?”

“Because it is prayer without pain!” replied the Elder. “To pray with the heart, we must hurt. Just as when we hit our hand or some other part of our body, our mind (nous) (“Nous: the highest faculty or power of the human soul, called by the Holy Fathers “the eye of the soul,” St. John Damascene, and “the spiritual nature of man,” St. Isaac the Syrian) is gathered to the point we are hurting, so also for the mind to gather in the heart, the heart must hurt.”

The Elder was then asked, “How can we preserve ourselves in this state when we don’t have some problem, some pain?”

He replied, “We should make the other’s pain our own!! We must love the other, must hurt for him, so that we can pray for him. We must come out little by little from our own self and begin to love, to hurt for other people as well, for our family first then for the large family of Adam, of God” (Athanasios Rakovalis, Talks with Father Paisios (Thessalonica, Greece: Orthodox Kypseli, 2000), pp. 123-24).

At another time the Elder said, “The more one hurts, the more divine consolation one receives, because otherwise it is not possible to stand the pain… God especially consoles those who hurt for others” (Ibid.,p. 124).

To his spiritual children the Elder wrote: “To some people your love will be expressed with joy and to others it will be expressed with your pain. You will consider everyone your brother or your sister, for we are all children of Eve (of the large family of Adam, of God). Then, in your prayer you will say: ‘My God, help those first who are in greater need, whether they are alive or reposed brothers in the Lord.’ At that point, you will share your heart with the whole world and you will have nothing but immense love, which is Christ” (Elder Paisios of Mount Athos, Epistles, p. 50).

On Distrusting Thoughts.

Secondly, Elder Paisios tells us that, if we are to grow in love toward our fellow man, we are to cut off those thoughts and feelings which are an offense against love: that is, judgments and resentments. He counseled that “We should never, even under the worst circumstances, allow a negative thought to penetrate our soul. The person, who, under all circumstances, is inclined to have positive thoughts, will always be a winner; his life will be a constant festivity, since it is constantly based on positive thinking” (Priestmonk Christodoulos Aggeloglou, Elder Paisios of the Holy Mountain Mount Athos, Greece, 1998, p. 31).

One of Elder Paisios’ spiritual sons recalls, “Elder Paisios always urged us to think positively. Our positive thinking, however, should not be our ultimate aim; eventually our soul must be cleansed from our positive thoughts as well, and be left bare, having as its sole vestment Divine Grace granted to us through Holy Baptism. ‘This is our aim,’ he used to say, ‘to totally submit our mind to the Grace of God. The only thing Christ is asking from us is our humility. The rest is taken care of by His Grace.

“‘In the beginning, we should willingly try to develop positive thoughts, which will gradually lead us to the perfect good, God, to Whom belongs all glory, honor and worship. On the contrary, to us belongs only the humility of our conceited attitude’ ” (Ibid., p. 29).

Elder Paisios’ teachings on thoughts and inner watchfulness, drawn from his own profound experience in the spiritual life, are particularly crucial for us who have been formed by modern Western culture. Because he spent so much time listening to people (both monastic and lay) and helping them with their problems, Elder Paisios became acutely aware of the various spiritual diseases afflicting modern Western man. Above all, he recognized — and sought to treat — the most prevalent disease: rationalism. Although the modern rationalist worldview was born in Western Europe during the Enlightenment era, it has progressively been inundating the entire world, including Orthodox lands such as Greece. Therefore, when Elder Paisios speaks to the spiritual malady of rationalism in contemporary Greece, he is also speaking to our spiritual malady in America and the West.

Ultimately, the malady of modern rationalism comes down to one essential ingredient: trusting the conclusions of one’s logical mind. We of the modern West have been raised with an underlying assumption, summed up in the well-known phrase of Rene Descartes at the beginning of the Enlightenment era: “I think, therefore I am.” The worldview of modern rationalism, having lost an awareness of the immortal soul in man, leads us to believe that our thoughts are v/ho we are, and, conversely, that we are the sum total of our thoughts. Therefore, we automatically feel that we have to trust our thoughts, to take a stand for them, to defend them as we would our own flesh and blood.

This is the essential fallacy of the modern worldview. It is precisely by placing absolute trust in the formulations of the fallen human mind — rather than in divine revelation — that modern Western man has come to water down or abandon his once-cherished Christian Faith. We Orthodox Christians living in the West must act against this influence by refusing to accord outright trust to our thoughts.

Elder Paisios teaches: “The devil does not hunt after those who are lost; he hunts after those who are aware, those who are close to God. He takes from them trust in God and begins to afflict them with self-assurance, logic, thinking, criticism. Therefore we should not trust our logical minds. Never believe your thoughts.

“Live simply and without thinking too much, like a child with his father. Faith without too much thinking works wonders. The logical mind hinders the Grace of God and miracles. Practice patience without judging with the logical mind.”

Elsewhere Elder Paisius counseled: “We ought always to be careful and be in constant hesitation about whether things are really as we think. For when someone is constantly occupied with his thoughts and trusts in them, the devil will manage things in such a way that he will make the man evil, even if by nature he was good.

“The ancient fathers did not trust their thoughts at all, but even in the smallest things, when they had to give an answer, they addressed the matter in their prayer, joining to it fasting, in order in some way to ‘force’ Divine Grace to inform them what was the right answer according to God. And when they received the ‘information,’ they gave the answer.

“Today I observe that even with great matters, when someone asks, before he has even had the time to complete his question, we interrupt him and answer him. This shows that not only do we not seek enlightenment from the Grace of God, but we do not even judge with the reason God gave us. On the contrary, whatever our thoughts suggest to us, immediately, without hesitation, we trust it and consent to it, often with disastrous results.

“Almost all of us view thoughts as being something simple and natural, and that is why we naively trust them. However, we should neither trust them nor accept them.

“Thoughts are like airplanes flying in the air. If you ignore them, there is no problem. If you pay attention to them, you create an airport inside your head and permit them to land!” (Ibid., pp. 29-30, 48).

A Gift from God to the World.

Nearly a decade has passed since the repose of Elder Paisios. In that time, several books by and about him have appeared not only in Greek but also in other languages, thus providing an opportunity for those outside of the Elder’s homeland to benefit from his life and counsels. Two books by the Elder’s spiritual children have now been published in English: Elder Paisios of the Holy Mountain by Priest-monk Christodoulos, and Talks with Father Paisios by Athanasios Rakovalis. Furthermore, the women’s monastery he helped to establish — the Holy Monastery of the Evangelist John the Theologian in Souroti, Greece — has now published English editions of all four books of the Elder’s writings: Saint Arsenios the Cappadocian, Elder Hadji-Georgis the Athonite, Athonite Fathers and Athonite Matters, and Epistles. The monastery is currently planning to publish English editions of all three books of the Elder’s discourses as well: With Pain and Love for Contemporary Man, Spiritual Wakefulness, and Spiritual Struggle.

From the books by and about Elder Paisios that are now available, we in the English-speaking world can become partakers of his deep store of spirituality and wisdom. Each line of his, coming from a heart overflowing with love for God and man, can rekindle our longings for closer communion with God and a more perfect love for our neighbor. Coming to know his beautiful soul as it expresses itself in words, we can come to love him as our father in the Faith. And since we believe that the souls of reposed righteous ones remain alive with our Lord Jesus Christ, we can learn from him as from one still alive, becoming, as it were, his posthumous disciples. In anticipation of his formal glorification by the Greek Orthodox Church, we can call upon him in prayer, asking him to help us on the path to Christ’s Kingdom.

As his spiritual daughters at the convent in Souroti have aptly written, “Elder Paisios gave himself completely to God, and God gave him to the whole world” (Elder Paisios of Mount Athos, Epistles, p. 10). God gave him to each of us Orthodox Christians, and it is ours to receive that gift and make use of it for the salvation of our souls and the souls of our suffering fellow men.

A Brief Life of Elder Paisios

On July 25, 1924, the future Elder Paisios (Eznepidis) was born to pious parents in the town of Farasa, Cappadocia of Asia Minor. The family’s spiritual father, the priest-monk Arsenios (the now canonized St. Arsenios of Cappadocia), baptized the babe with his own name, prophesying his future profession as a monk. A week after the baptism (and barely a month after his birth) Arsenios was driven, along with his family, out of Asia Minor by the Turks. St. Arsenios guided his flock along their four-hundred-mile trek to Greece. After a number of stops along the way, Arsenios’ family finally ended up in the town of Konitsa in Epiros (northwestern Greece). St. Arsenios had reposed, as he had prophesied, forty days after their establishment in Greece, and he left as his spiritual heir the infant Arsenios.

The young Arsenios was wholly given over to God and spent his free time in the silence of nature, where he would pray for hours on end. Having completed his elementary education, he learned the trade of carpentry. He worked as a carpenter until his mandatory military service. He served in the army during the dangerous days of the end of World War II. Arsenios was brave and self-sacrificing, always desiring to put his own life at risk so as to spare his brother. He was particularly concerned about his fellow soldiers who had left wives and children to serve.

Having completed his obligation to his country, Arsenios received his discharge in 1949 and greatly desired to begin his monastic life on the Holy Mountain. Before being able to settle there, however, he had to fulfill his responsibility to his family, to look after his sisters, who were as yet unmarried. Having provided for his sisters’ future, he was free to begin his monastic vocation with a clean conscience. In 1950 he arrived on Mount Athos, where he learned his first lessons in the monastic way from the virtuous ascetic Fr. Kyril (the future abbot of Koutloumousiou Monastery); but he was unable to stay at his side as he had hoped, and so was sent to the Monastery of Esphigmenou. He was a novice there for four years, after which he was tonsured a monk in 1954 with the name Averkios. He was a conscientious monk, finding ways to both complete his obedience’s (which required contact with others) and to preserve his silence, so as to progress in the art of prayer. He was always selfless in helping his brethren, unwilling to rest while others worked (though he may have already completed his own obedience’s), as he loved his brothers greatly and without distinction. In addition to his ascetic struggles and the common life in the monastery, he was spiritually enriched through the reading of soul-profiting books. In particular, he read the Lives of the Saints, the Gerontikon, and especially the Ascetical Homilies of St. Isaac the Syrian.

Soon after his tonsure, Monk Averkios left Esphigmenou and joined the (then) idiorrhythmic brotherhood of Philotheou Monastery, where his uncle was a monk. He put himself under obedience to the virtuous Elder Symeon, who gave him the Small Schema in 1956, with the new name Paisios. Fr. Paisios dwelt deeply on the thought that his own spiritual failures and lack of love were the cause of his neighbor’s shortcomings, as well as of the world s ills. He harshly accused himself, pushing himself to greater self-denial and more fervent prayer for his soul and for the whole world. Furthermore, he cultivated the habit of always seeking the “good reason” for a potentially scandalous event and for people’s actions, and in this way he preserved himself from judging others. For example, pilgrims to Mount Athos had been scandalized by the strange behavior and stories told by a certain monk, and, when they met Elder Paisios, they asked him what was wrong with the monk. He warned them not to judge others, and that this monk was actually virtuous and was simply pretending to be a fool when visitors would come, so as to preserve his silence.

In 1958 Elder Paisios was asked to spend some time in and around his home village of Konitsa so as to support the faithful against the proselytism of Protestant groups. He greatly encouraged the faithful there, helping many people. Afterwards, in 1962, he left to visit Sinai where he stayed for two years. During this time he became beloved of the Bedouins, who benefitted both spiritually as well as materially from his presence. The Elder used the money he received from the sale of his carved wooden handicrafts to buy them food.

On his return to Mount Athos in 1964, Elder Paisios took up residence at the Skete of Iviron before moving to Katounakia at the southernmost tip of Mount Athos for a short stay in the desert there. The Elder’s failing health may have been part of the reason for his departure from the desert. In 1966, he was operated on and had part of his lungs removed. It was during this time of hospitalization that his long friendship with the then young sisterhood of St. John the Theologian in Souroti, just outside of Thessalonica, began. During his operation he greatly needed blood and it was then that a group of novices from the monastery donated blood to save him. Elder Paisios was most grateful, and after his recovery did whatever he could, materially and spiritually, to help them build their monastery.

In 1968 he spent time at the Monastery of Stavronikita helping with its spiritual as well as material renovation. While there he had the blessing of being in contact with the ascetic Elder Tychon who lived in the hermitage of the Holy Cross, near Stavronikita. Elder Paisios stayed by his side until his repose, serving him selflessly as his disciple. It was during this time that Elder Tychon clothed Fr. Paisios in the Great Schema. According to the wishes of the Elder, Fr. Paisios remained in his hermitage after his repose. He stayed there until 1979, when he moved on to his final home on the Holy Mountain, the hermitage Panagouda, which belongs to the Monastery of Koutloumousiou.

It was here at Panagouda that Elder Paisios’ fame as a God-bearing elder grew, drawing to him the sick and suffering people of God. He received them all day long, dedicating the night to God in prayer, vigil and spiritual struggle. His regime of prayer and asceticism left him with only two or three hours each night for rest. The self-abandon with which he served God and his fellow man, his strictness with himself, the austerity of his regime, and his sensitive nature made him increasingly prone to sickness. In addition to respiratory problems, in his later days he suffered from a serious hernia that made life very painful. When he was forced to leave the Holy Mountain for various reasons (often due to his illnesses), he would receive pilgrims for hours on end at the women’s monastery at Souroti, and the physical effort which this entailed in his weakened state caused him such pain that he would turn pale. He bore his suffering with much grace, however, confident that, as God knows what is best for us, it could not be otherwise. He would say that God is greatly touched when someone who is in great suffering does not complain, but rather uses his energy to pray for others.

In addition to his other illnesses he suffered from hemorrhaging which left him very weak. In his final weeks before leaving the Holy Mountain, he would often fall unconscious. On October 5, 1993 the Elder left his beloved Holy Mountain for the last time. Though he had planned on being off the mountain for just a few days, while in Thessalonica he was diagnosed with cancer that needed immediate treatment. After the operation he spent some time recovering in the hospital and was then transferred to the monastery at Souroti. Despite his critical state he received people, listening to their sorrow and counseling them.

After his operation, Elder Paisios had his heart set on returning to Mount Athos. His attempts to do so, however, were hindered by his failing health. His last days were full of suffering, but also of the joy of the martyrs. On July 11, 1994, he received Holy Communion for the last time. The next day, Elder Paisios gave his soul into God’s keeping. He was buried, according to his wishes, at the Monastery of St. John the Theologian in Souroti. Elder Paisios, perhaps more than any other contemporary elder, has captured the minds and hearts of Greek people. Many books of his counsels have been published, and the monastery at Souroti has undertaken a great work, organizing the Elder’s writings and counsels into impressive volumes befitting his memory. Thousands of pilgrims visit his grave each year, so as to receive his blessing.

Source: www.fatheralexander.org