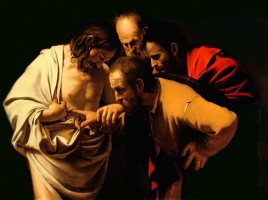

As the apostle Thomas demonstrates, a biblical name is never just a name. “Thomas” (“the twin”) is a character description of ambiguity and duplicity that rings true when the apostle misses out on beholding the risen Christ. Not content with hearing about it from the other disciples, he issues a bold ultimatum: Unless he himself can see and touch Jesus’ wounds, he will not believe.

I sometimes feel conflicted about this passage. In an age of rationalistic attacks on faith, it seems to present a reckless litmus test for skeptics.

I sometimes feel conflicted about this passage. In an age of rationalistic attacks on faith, it seems to present a reckless litmus test for skeptics.

It reminds me of a guy I knew in college who bragged about standing in a field during a thunderstorm, hurling obscenities skyward and daring any deity who might be listening to strike him dead. When nothing happened, he concluded there was no one up there. With less drama, but similar results, Thomas’ words aid modern Christians who prefer unwavering doubt to the faux pas of firm faith.

Dispensing with modernist baggage, I see in Thomas not some patron saint of eternal fence sitters, but an example of someone searching for the one thing needful: union with Christ. I see in Thomas the same thirst for God that drove my transformation from a functional atheist to an Orthodox priest.

I remember the first time I encountered prayer. I was 6 or 7. An older cousin was spending the night. After lights out, I heard him mumbling in the dark.

“Brian, what are you doing?” I asked.

“I’m praying,” he replied.

“Oh,” I said, hesitating to reveal my ignorance. “What’s that?”

Brian explained that praying meant talking to God. I had heard of God before, but usually when people swore. Nevertheless, I gave it a try. It brought a sense of comfort, perhaps even purpose, so I kept it up. Cousin Brian was the most effective Mormon missionary I ever met, and he wasn’t even trying.

Years went by and I wanted to know more about this God I naively prayed to, so in sixth grade I decided to read a fat tome my parents kept on the bottom shelf of the coffee table. It had a holographic, 3-D sticker on the cover with some bearded dudes at a dinner table, but that wasn’t tacky enough to keep me away. So I read the Bible from cover to cover — in King James English that greatly discouraged me.

When I came to Acts (about a year later), I got excited. Despite the spiritual ignorance of my brief existence, I’d begun to feel, if not faith itself, then at least a desire for it. Acts showed me there was a place I could learn more: the Church. I issued an ultimatum not unlike Thomas’: Unless you show me where to go, I cannot believe. As with Thomas, God obliged my request with a vengeance.

When I stepped through the doors of an Orthodox church years later, I knew that although the vestibule appeared empty, it was not.

This was no warm, fuzzy feeling. It was sheer terror. I was standing in the presence of God. And I was scared.

Palms sweating, heart pounding, bowels clenching, feet frozen to the floor, I gaped about me at a completely foreign environment illumined by the dancing light of oil lamps.

I stood paralyzed by impulses to go further inside, and to run quickly away.

Could this be what Thomas felt when the Lord appeared to him? Is this what compelled him to exclaim, “My Lord and my God!”?

Many who grow up with a faith to take for granted misread Thomas’ ultimatum as a concession to the intellectual respectability of agnosticism.

A few of us, however, travel in the opposite direction. We begin with that doubt and see it as emptiness only God can fill. It may be that people are flooding out of churches these days, but now and then, a drop trickles uphill.

Source: The Pueblo Chieftain Online

You might also like:

Doubting Thomas by Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann

St. Thomas Sunday by Fr. Sergei Sveshnikov

On Thomas Sunday by Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapotvitsky) of Kiev and Galicia (+1936)