During the period from Pascha to Pentecost, we can’t help but notice the matching of stories between the Gospel and the life of the early Church. This is especially true when we compare Luke and Acts, since they are considered two volumes of a set. The Gospel relates the life of Christ in the flesh, while Acts relates the story of the Risen Christ at work in the church. But we also see this matching in John’s Gospel and Acts, the two texts read closely during this period.

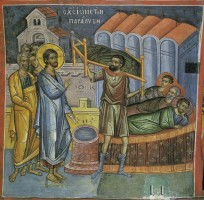

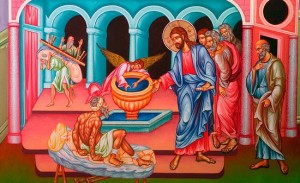

The early church repeats many of the same stories of healing that we find in the ministry of Christ. I’m not saying that these are the same stories told over again in the context of the church, but they demonstrate the continuity of faith and life particularly in regard to the healing power the church brings to the world.

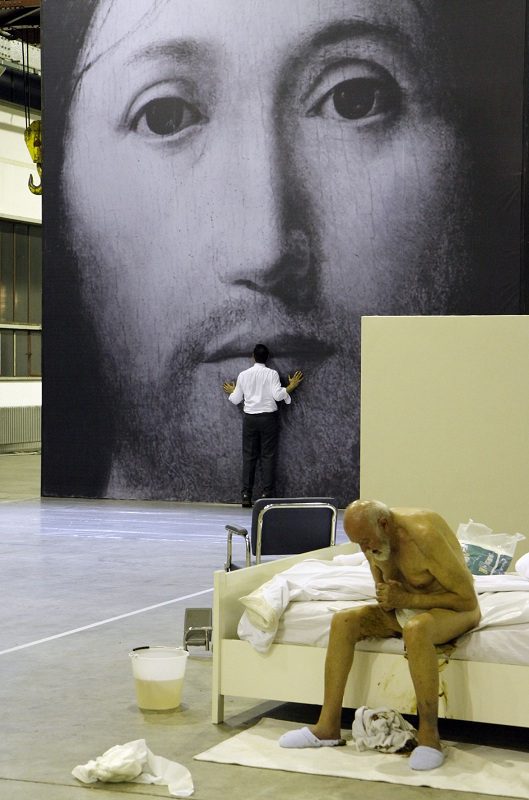

When we hear these stories we are often tempted to console ourselves by saying that this was the early church, and it was a much different period in history than now. This becomes a way to excuse ourselves when we see the woeful lack of healing that takes place in so many churches, perhaps our own. So often the church looks moribund, destitute and struggling, rather than full of liveliness, healing, and hope. It is so easy to lose sight of our purpose, calling, and real ministry in the welter of activity, administration, and distraction.

Every story of healing in the New Testament comes to us with a message on two levels, one physical and the other spiritual. They are connected: there is a peculiar form of blindness that is spiritual and the healing of physical blindness takes that into consideration. So it is also with paralysis.

The paralytic is a person who cannot move. Mobility is a major part of our lives. When our bodies no longer move and the breath no longer moves through them, we are dead. Every physical therapist or trainer will tell you that, as you age, it is particularly important to keep moving and flexible.

Current psychological research even claims that we were meant to be nomads or pilgrims, and that our humanity does not require a settled life. This would certainly ring true for pilgrims and monastics down to our own day.

Any inability to move affects both body and soul. Without mobility we are trapped. We can become inflexible in spirit as well as in body. All this and more is what we are freed from when the Risen Christ comes into our lives for healing through his Body, the Church. We are free to move forward once again.

Healing makes sense in a contemporary setting. The church remains a place of healing, in fact that is its primary characteristic according to the many writings of Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos. We are a therapeutic community and, if not, we are not living up to the high calling to which we have been called.

The healings that take place in the Body of Christ today may not seem as dramatic as the ones depicted in scripture but they are nonetheless real. When people are enabled to drop the crutch of addiction through the power of the cross and resurrection, real healing has happened. When people are enabled to drop the withering limitations of their anger, real healing has happened. When people are enabled to move beyond coldness and disinterest in others, their paralysis has been healed.

Christ calls us all to this kind of healing. It may not be immediate and total, like so many of the healings in Scripture. We may need to revisit our pockets of paralysis time and again before they are cured. We need to utilize confession to drive out the passions that fuel our particular and personal forms of paralysis, but they will yield in the end, as well, and we shall be healed. St Irenaeus said it so well: “the glory of God is a human being fully realized.” That realization takes place as we are healed, whether slowly or swiftly, through the power of Christ and of his Resurrection. Don’t make excuses like the paralytic in the story. The gift is yours to claim. Will you ask for this mercy?