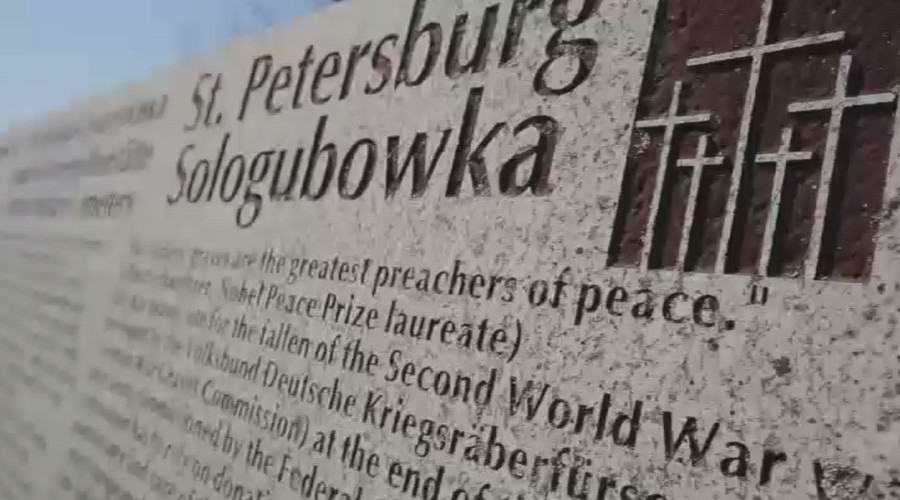

More than 75,000 World War II troops are buried at the German military cemetery, which was opened in the Russian village of Sologubovka some 80 kilometers from Saint Petersburg in 2000, Father Vyacheslav said.

According to the official website of the German War Graves Commission, an NGO responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of German war graves in Europe and North Africa, some 54,000 German WWII soldiers are buried at the cemetery, which has space for 80,000 graves. The remains of more than 35,000 German soldiers have been identified so far, the commission says.

“We’re in a unique place for Russian-German relations,” Father Vyacheslav, who is the archpriest at the nearby Uspensky Church, told RT. “In my view, it’s the largest peace-making project between Russia and Germany, which was initiated by a small village parish, but prompted response from politicians and the general public in the whole of Europe,” he said.

Sologubovka was chosen to host the cemetery because 3,500 German troops were buried there during World War II.

“It was the deciding factor in putting the cemetery here… Those remains were exhumed and moved to the spot assigned for the burial site,” Father Vyacheslav said.

According to the priest, the cemetery currently hosts “the remains of German servicemen from the whole of (Russia’s) northwest,” but the majority are from nearby districts in Leningrad Region.

The Nazi forces were never able to take the city of Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg).

Instead, they put Leningrad under an exhausting siege, which lasted for 872 days – from September 8, 1941 to January 27, 1944 – and claimed the lives of over 640,000 civilians, according to official statistics. According to new data provided by the Russian Defense ministry, more than 1.4 million people died during the siege of Leningrad.

Before the cemetery was opened, the remains of German troops discovered in Russia were cremated, the priest said.

“According to the agreement signed between Russia and Germany in 1992, the German side has no right to personify the graves (in Sologubovka). We know who is buried there and where within about two meters, but no personal signs are placed here, although we can see the names of everybody engraved on a stone,” Father Vyacheslav said.

The priest told RT that whole pilgrimages arrive from Germany to search for their relatives and pay their respects, adding that he tries to help all who come.

He explained that the German troops laid to rest in Sologubovka

“aren’t subjects of the Russian Orthodox Church. Therefore, they aren’t being mourned via the Orthodox canon… but the right understanding and the ability to see the devastating results of war make this cemetery very important for the Russians as well.”

Father Vyacheslav pushed for the creation of the German military cemetery in Sologubovka because he believes that “every soldier has the right to a grave.”

“We must commit the soldier to earth no matter, who he was… We don’t battle the dead… War crimes and war criminals must be condemned, but it’s pointless to fight with the remains,” he explained.

The priest spoke of a Russian military officer who visits the German cemetery every year on May 9 and renders a salute, saying that “those are soldiers as well. A soldier doesn’t answer for his command. They were just following orders.”

The German cemetery is important because

“if the winner isn’t benevolent it means that he hasn’t really won… If he’s vengeful; if he’s cruel; if he doesn’t surpass the defeated side on an ethical level, then this victory is temporary. I think the Russians won that war not only with weapons, but with the moral values professed by our people and our culture,” he said.

Besides the cemetery, the “peacemaking project” in Sologubovka includes the Uspensky Church and the Park of Peace, Father Vyacheslav said.

The local Church was “restored with the funds of not only Russian Germans, but other Europeans as well,” he said.

During the war, it was a reference point for Nazi artillery and was destroyed, remaining “in ruins, covered with trees and bushes,” the priest said.

The Uspensky Church had been slated for demolition to make room for a road leading to the new cemetery, but the involvement of Father Vyacheslav saved the house of worship, which is now preserved.

“Eventually, we came to the conclusion that the rebuilding the church in a joint effort would become a sign of reconciliation. We maintained the church, built the cemetery, and united those two elements in the Park of Peace,” Father Vyacheslav said.

The Park of Peace – “a landscape area, with planting, architectural elements, and sculptures” designed to “underline the tragedy of war and the blessedness of peace” – is also one of a kind in Russia, he explained.

Father Vyacheslav also told RT that not everybody welcomed the idea of creating a cemetery for enemy troops. Among those who opposed it were veterans who had fought the Nazis.

However, many of the opponents eventually understood the importance of such a burial site for the future of peaceful relations between Russia and Germany.

“How did it happen? We simply took them to our (Russian military) cemeteries in Germany. They saw that their friends were lying in well-cared-for graves, with their names remembered and engraved in stone,” the priest said.

He called what happened next a “miracle,” as “when those old people, the veterans, returned (to Sologubovka), they laid flowers on the German graves.”