By John Blake, CNN

(CNN) – Can you speak Christian?

Have you told anyone “I’m born again?” Have you “walked the aisle” to “pray the prayer?”

Did you ever “name and claim” something and, after getting it, announce, “I’m highly blessed and favored?”

Many Americans are bilingual. They speak a secular language of sports talk, celebrity gossip and current events. But mention religion and some become armchair preachers who pepper their conversations with popular Christian words and trendy theological phrases.

If this is you, some Christian pastors and scholars have some bad news: You may not know what you’re talking about. They say that many contemporary Christians have become pious parrots. They constantly repeat Christian phrases that they don’t understand or distort.

Marcus Borg, an Episcopal theologian, calls this practice “speaking Christian.” He says he heard so many people misusing terms such as “born again” and “salvation” that he wrote a book about the practice.

Marcus Borg, an Episcopal theologian, calls this practice “speaking Christian.” He says he heard so many people misusing terms such as “born again” and “salvation” that he wrote a book about the practice.

People who speak Christian aren’t just mangling religious terminology, he says. They’re also inventing counterfeit Christian terms such as “the rapture” as if they were a part of essential church teaching.

The rapture, a phrase used to describe the sudden transport of true Christians to heaven while the rest of humanity is left behind to suffer, actually contradicts historic Christian teaching, Borg says.

“The rapture is a recent invention. Nobody had thought of what is now known as the rapture until about 1850,” says Borg, canon theologian at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland, Oregon.

How politicians speak Christian

Speaking Christian isn’t confined to religion. It’s infiltrated politics.

Political candidates have to learn how to speak Christian to win elections, says Bill Leonard, a professor of church history at Wake Forest University’s School of Divinity in North Carolina.

One of our greatest presidents learned this early in his career. Abraham Lincoln was running for Congress when his opponent accused him of not being a Christian. Lincoln often referred to the Bible in his speeches, but he never joined a church or said he was born again like his congressional opponent, Leonard says.

“Lincoln was less specific about his own experience and, while he used biblical language, it was less distinctively Christian or conversionistic than many of the evangelical preachers thought it should be,” Leonard says.

Lincoln won that congressional election, but the accusation stuck with him until his death, Leonard says.

One recent president, though, knew how to speak Christian fluently.

During his 2003 State of the Union address, George W. Bush baffled some listeners when he declared that there was “wonder-working power” in the goodness of American people.

Evangelical ears, though, perked up at that phrase. It was an evangelical favorite, drawn from a popular 19th century revival hymn about the wonder-working power of Christ called “In the Precious Blood of the Lamb.”

Leonard says Bush was sending a coded message to evangelical voters: I’m one of you.

“The code says that one: I’m inside the community. And two: These are the linguistic ways that I show I believe what is required of me,” Leonard says.

Have you ‘named it and claimed it’?

Ordinary Christians do what Bush did all the time, Leonard says. They use coded Christian terms like verbal passports – flashing them gains you admittance to certain Christian communities.

Say you’ve met someone who is Pentecostal or charismatic, a group whose members believe in the gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as healing and speaking in tongues. If you want to signal to that person that you share their belief, you start talking about “receiving the baptism of the Holy Ghost” or getting the “second blessings,” Leonard says.

Translation: Getting a baptism by water or sprinkling isn’t enough for some Pentecostals and charismatics. A person needs a baptism “in the spirit” to validate their Christian credentials.

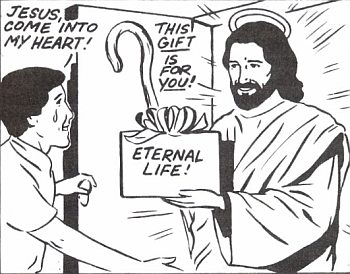

Or say you’ve been invited to a megachurch that proclaims the prosperity theology (God will bless the faithful with wealth and health). You may hear what sounds like a new language.

Prosperity Christians don’t say “I want that new Mercedes.” They say they are going to “believe for a new Mercedes.” They don’t say “I want a promotion.” They say I “name and claim” a promotion.

The rationale behind both phrases is that what one speaks aloud in faith will come to pass. The prosperity dialect has become so popular that Leonard has added his own wrinkle.

“I call it ‘name it, claim it, grab it and have it,’ ’’ he says with a chuckle.

Some forms of speaking Christian, though, can become obsolete through lack of use.

Few contemporary pastors use the language of damnation – “turn or burn,” converting “the pagans” or warning people they’re going to hit “hell wide open” – because it’s considered too polarizing, Leonard says. The language of “walking the aisle” is also fading, Leonard says.

Appalachian and Southern Christians often told stories about staggering into church and walking forward during the altar call to say the “sinner’s prayer” during revival services that would often last for several weeks.

“People ‘testified’ to holding on to the pew until their knuckles turned white, fighting salvation all the way,” Leonard says. “You were in the back of the church, and you fought being saved.”

Contemporary churchgoers, though, no longer have time to take that walk, Leonard says. They consider their lives too busy for long revival services and extended altar calls. Many churches are either jettisoning or streamlining the altar call, Leonard says.

“You got soccer, you got PTA, you got family responsibilities – the culture just won’t sustain it as it once did,” Leonard says.

Even some of the most basic religious words are in jeopardy because of overuse.

Calling yourself a Christian, for example, is no longer cool among evangelicals on college campuses, says Robert Crosby, a theology professor at Southeastern University in Florida.

“Fewer believers are referring to themselves these days as ‘Christian,’ ” Crosby says. “More are using terms such as ‘Christ follower.’ This is due to the fact that the more generic term, Christian, has come to be used within religious and even political ways to refer to a voting bloc.”

What’s at stake

Speaking Christian correctly may seem like it’s just a fuss over semantics, but it’s ultimately about something bigger: defining Christianity, says Borg, author of “Speaking Christian.”

Christians use common words and phrases in hymns, prayers and sermons “to connect their religion to their life in the world,” Borg says.

“Speaking Christian is an umbrella term for not only knowing the words, but understanding them,” Borg says. “It’s knowing the basic vocabulary, knowing the basic stories.”

When Christians forget what their words mean, they forget what their faith means, Borg says.

Consider the word “salvation.” Most Christians use the words “salvation” or “saved” to talk about being rescued from sin or going to heaven, Borg says.

Yet salvation in the Bible is seldom confined to an afterlife. Those characters in the Bible who invoked the word salvation used it to describe the passage from injustice to justice, like the Israelites’ liberation from Egyptian bondage, Borg says.

“The Bible knows that powerful and wealthy elites commonly structure the world in their own self-interest. Pharaoh and Herod and Caesar are still with us. From them we need to be saved,” Borg writes.

And when Christians forget what their faith means, they get duped by trendy terms such as the rapture that have little to do with historical Christianity, he says.

The rapture has become an accepted part of the Christian vocabulary with the publication of the megaselling “Left Behind” novels and a heavily publicized prediction earlier this year by a Christian radio broadcaster that the rapture would occur in May.

But the notion that Christians will abandon the Earth to meet Jesus in the clouds while others are left behind to suffer is not traditional Christian teaching, Borg says.

He says it was first proclaimed by John Nelson Darby, a 19th century British evangelist, who thought of it after reading a New Testament passage in the first book of Thessalonians that described true believers being “caught up in the clouds together” with Jesus.

Christianity’s focus has long been about ushering in God’s kingdom “on Earth, not just in heaven,” Borg says.

“Christianity’s goal is not to escape from this world. It loves this world and seeks to change it for the better,” he writes.

For now, though, Borg and others are also focusing on changing how Christians talk about their faith.

If you don’t want to speak Christian, they say, pay attention to how Christianity’s founder spoke. Jesus spoke in a way that drew people in, says Leonard, the Wake Forest professor.

“He used stories, parables and metaphors,” Leonard says. “He communicated in images that both the religious folks and nonreligious folks of his day understand.”

When Christians develop their own private language for one another, they forget how Jesus made faith accessible to ordinary people, he says.

“Speaking Christian can become a way of suggesting a kind of spiritual status that others don’t have,” he says. “It communicates a kind of spiritual elitism that holds the spiritually ‘unwashed’ at arm’s length.”

By that time, they’ve reached the final stage of speaking Christian – they’ve become spiritual snobs.