I do not have the courage to begin what I have to say to you now with the habitual words ‘In the Name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit’, because it is more a cry of heaviness of my own soul, which I want to share with you, hoping that God, who shares with us all the pain of the world, all the tragedy of it, shares it also.

We are a divided Christendom; and we do not always realise how tragic that is, because we live on a number of levels. There are few moments when the difficult, at times abstruse doctrines that differentiate us play any role. How often does the primacy of the Pope determine the actions of a Roman Catholic believer in the course of the day? How often does the teaching of the Orthodox Church of the Trinity make a difference to his or her behaviour to one another? How often does such and such a passage from the Scriptures quoted by Calvin and other theologians of the Reformation determine our actions?

We live and act and relate to one another on a quite different level. And this level is either mutual recognition, acceptance, and at best mutual love; or on the contrary estrangement, misunderstanding and at times hatred.

We do not express feelings of hatred now as they were expressed a century ago. But I remember when I was a boy in a primary school in Vienna, how in the first week I was sent by the headmistress, who knew nothing about what Orthodoxy was, first of all to the rabbi — because ‘Orthodox’ sounded to her like an Old Testamental expression.

He looked at me, asked why I had an uncovered head, and when I replied, ‘Because my mother has taught me never to wear a hat in a room because there can be a crucifix or an icon there’, he looked at me and said, ‘A Christian — in my form? Out of here!’

I was called by the headmistress in the corridor, who recognising me therefore as a Christian, sent me to the Roman Catholic priest. He asked me what I was, and hearing that I was an Orthodox boy he said, ‘A heretic in my form? Out!’ And this was the end of all the religious education I received.

This does not happen now. But the estrangement remains, to a very great extent. And it remains when we meet in terms of intellection, when we compare formulas, when we compare theological statements. I remember an extraordinary discussion reported about a Greek bishop in the sixteenth century with a Roman theologian. The Roman theologian wanted him to answer his questions in the terms of Thomistic philosophy and theology. And the Greek bishop could not answer them on those terms, because they were alien to him. And he was apparently defeated. And yet he was right; because it was not a competition between two philosophical systems but the proclamation of a living faith.

We are in the same position now. Dividedness has existed among the Christians from the beginning. You remember how Christ’s disciples quarrelled: who among them was the greatest? And Christ answered: This child. And what did He see in this child? Purity of heart; purity of mind; an ability to be totally open to love and tenderness and acceptance of the other. The disciples learnt exactly this when the Holy Spirit came upon them, and when they went round preaching the Gospel but not attacking anything or anyone — but only proclaiming that God so loved the world that He had given His Only-begotten Son unto death that the world might be saved.

This is the truth on which we can build our unity. We must become like the child: pure in heart, open to God, open to our neighbour, in simplicity and in love. We cannot, indeed we have no right to reject or turn away from the teaching of our respective communities. But we must ask ourselves how much in this teaching is of God, of the Spirit, and how much is an attempt at expressing in terms of the world, of the philosophies of the time, something which is beyond them.

And also we must learn to approach one another with new eyes. For centuries we have been in competition. We have argued. We have tried to convert one another, to prove to the other that he was wrong and we were right. No.

I remember Professor Zander, one of the great ecumenical theologians of the twentieth century, who wrote in a book called Action and Vision how he sees the rapprochement of believers. He said to begin with, two persons are one. And then they think, they try to understand, they try to formulate their belief. They present that formulation to one another and the other cannot accept it, because he has also done the same, gone the same way, and come to another way of expressing the one truth. And the moment comes when they no longer are one.

They turn away from one another, and as Professor Zander puts it in a very pictorial way they still feel with their backs the shoulders of the other, but they are infinitely far away from each other, because they are looking into another infinity of distance. And then they go away. They become more and more ingrained in what begins to be the only expression of truth acceptable to them. It becomes not only the expression according to their capability of mind. It becomes The Truth. And the other becomes an alien, a heretic, an enemy of God — or simply a stranger who has fallen out of the boat.

Then one day, when they are far away, when bitterness has waned and separatedness becomes painful because there is still in their hearts a love of the other, they ask themselves: what has happened to him since we parted? And they turn round and look, until in the distance they see a figure. It’s like a tree, like a statue, like a dead object. But know it is their friend, and they begin to move towards one another; and the nearer they come, the more they recognise one another. And they meet face to face. At that moment they say to one another: in the centuries of separation what have you learnt of God? Of yourself? Of me? And they begin to share — to share their separatedness and beyond it, what they still share of unity in the only God whom they worship.

This is what is happening to us now. There was a moment when we all, in the early centuries, were one. Then earthly wisdom came and divided us. We wanted to express our faith in terms of the philosophies of the time. And then we went astray farther and farther. And we began later to meet each other; at times partly, only.

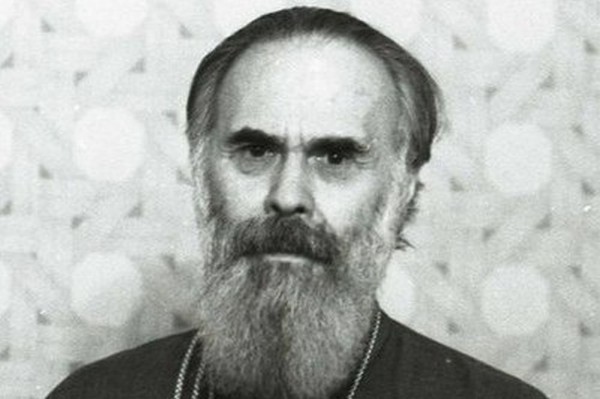

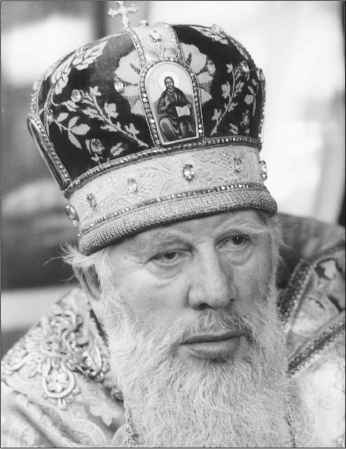

I remember forty years ago the first conference of the World Council of Churches at which the Russian Orthodox Church was present. We asked Bishop Ioann Wendland to speak for us a few words of greeting, and the essence of what he said I have not forgotten. He thanked the World Council of Churches for accepting us in spite of the fact that we were so different from them. And he added: We are not bringing to you a new Gospel. We are bringing to you the simplicity which the great minds have forgotten: the simple truth of Christ. We have been unable to live worthily of it. Take from us what we bring, and bear the fruits which we have proved unable to bear.

Isn’t it something which each denomination can say to the other? With one provision that we turn to God Himself and say: And yet there is a lot I must repent for, there is a lot I must learn from my neighbour, and it is only together as one body that we will be Thy Church — Thy Church in its entirety, not in separation but in the Holy Spirit — become the place where God, One in the Trinity, is at one with the humanity that has accepted to renounce all worldly wisdom, to know only the wisdom of God.

This is what I believe is the point at which we are. This is what I say from all my heart, although I dare not say that in the name of God Himself, but as a result of a long life, with many mistakes, and joy, the incredible joy of being loved by God, together with all, all the people, all the Creation. Amen.

Sermon at Vespers for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity

23rd January 2002