Martin Luther once wrote that the first chapter of Genesis ‘is written in the simplest language; yet it contains matters of the utmost importance and very difficult to understand. It was for this reason, as St. Jerome asserts, that among the Hebrews it was forbidden for anyone under thirty to read the chapter or to expound it to others.’(1)

The vast number of interpretations of the creation account in Genesis over recent centuries suggests that Luther may have had a point. But the problem is in fact much simpler than people make it out to be.

At the risk of oversimplification, I would say that there are three schools of thought today regarding the interpretation of the first chapter of Genesis:

1) Τhere are those who appeal to modern science in order to dismiss Genesis as irrelevant and to disparage it as nothing more than the survival of a primitive pre-scientific view of the world.

2) There are those who try to interpret Genesis in a way that conforms to the theories and discoveries of modern science in order to uphold the relevance of Genesis.

3) There are those who believe that Genesis is to be taken literally, regardless of the discoveries of modern science.

The main problem with all three of these schools of thought is that they wrongly assume that Genesis is a work of creation history rather than a work of theology. The relevance of Genesis does not lie in its explanation of how the world was created. The message of the creation account of Genesis is that all is created by God and for God, and man has a God-given purpose on this planet, which means that man can never be truly happy for as long as he is not carrying out that purpose. The question of how God created man and the world is irrelevant for theology. Even as early as the fourth century, the Church Father Severianos of Gabbala writes: ‘Moses did not say these things as an historian, but as a prophet’.(2)

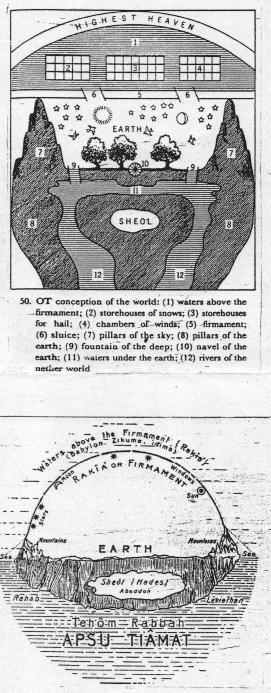

Another problem of interpretation seems to stem from a rather bizarre understanding of the ‘infallibility of scripture’. When we say that the biblical authors were divinely inspired to write what they wrote, it does not mean that they were given some sort of extraordinary understanding of science, and that is simply because such matters are not pertinent to human salvation. It is in fact important to bear this in mind when reading many passages from the scriptures, and particularly the first chapter of Genesis. Note, for example, these two diagrams of Ancient Hebrew Cosmology: the Hebrew people in the time of Moses believed that the world looked something like this. It is almost impossible to understand certain passages of scripture without having this world-view in mind. For example, in verses 6 to 8 of chapter 1 of Genesis, we read:

‘And God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.” And God made the firmament and separated the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day’.

‘And God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.” And God made the firmament and separated the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day’.

What on earth is that all about? What is this ‘firmament’ when it is not at home? A look at the top diagram will give us a clue. In the middle we have the earth and the sky. Right at the top we have the highest heaven, which was believed to be the dwelling place of God. Above the sky we have the firmament of which the scripture speaks. In-between the firmament and the highest heaven we have the waters above the firmament, containing the storehouses of snows, the storehouses for hail and the chambers of winds, and within the firmament we have windows through which the snow, hail, wind, and waters (rain) would come through.

In the second diagram we see a similar world-view, and you will notice at the bottom left and right corners within the sea we see written ‘Rahab’ and ‘Leviathan’ – two sort of sea monsters that the Hebrews believed lived in the depths of the sea. And in Genesis chapter 1 verse 21 we read: ‘So God created the great sea monsters…’, which could be referring to this Rahab and this Leviathan. Also, those of you who attend vespers should be familiar with Psalm 103 (104): ‘…the great sea wherein are things creeping and innumerable, both small and great. There go the ships; there is that leviathan whom thou hast made to play therein’.

So it is important to remember that, when we read the Scriptures, we can not understand everything with modern minds. We must try to enter the minds of the authors and understand how they thought.

There is a third problem with interpreting scripture, and that is people tend to forget that just like in our own modern languages, so in biblical language, there is poetry, there are idioms and figures of speech. It is not the sort of language one would expect to find in an instruction manual. If I were to say, ‘the traffic today was a nightmare’, none of you would think that I mean it was a figment of the imagination. Yet when we find such language in the scriptures, some people often think that it is to be taken literally. Even the third century theologian, Origen of Alexandria, makes it clear that there are many passages of scripture which are not to be taken literally. In commenting on Genesis, he points out that in the first chapter of Genesis ‘day’ and ‘night’ exist before the creation of the ‘sun’ and the ‘sky’. Therefore ‘day’ and ‘night’ are not meant to be taken literally. ‘Who is so ignorant’, he writes, ‘as to suppose that God planted trees in paradise, like a gardener; or that he took an afternoon walk there?’(3)

So, given that the creation account in Genesis was never intended to be a work of science or history, what is its message and purpose? While science tries to answer the question ‘how?’, and philosophy tries to answer the question ‘why?’, theology tries to answer the question ‘who?’. As I already said, the message of Genesis is that all is created by God and for God; but the account of creation goes further than this: it tells us who that God is and, by extension, what man is, for man is made in His image. Let us therefore examine Genesis chapter 1, verse 26:

‘Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let him have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth”.’

The point of greatest interest here is the use of the first person plural: ‘let us make man in our image’. There are three well-known interpretations for the use of the plural.

1) God is speaking with the angels.

2) It is the plural of majesty (the royal ‘we’).

3) The three persons of the Trinity are speaking together.

The first interpretation does not stand up to scrutiny, because no one has ever countenanced that man was made in the image of God and the angels. Man was made in the image of God alone.

The second interpretation does not stand up to scrutiny, because nowhere else in the scriptures is the royal ‘we’ used.

The third interpretation is the correct one and that of the Church Fathers: the three persons of the Trinity are speaking; man is made in the image not of one person, not of God the Father alone, but in the image of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This is of great importance, because it means that man is created by a plurality of persons in one essence. ‘God is love’ because God is more than one person. Love must have an object: it can not exist without more than one person. Therefore, man is made for union and communion with others: he is a ‘social being’. This is why God says in Genesis chapter 2, verse 13, “It is not good for man to be alone”. Man, being created in the Image of the Trinity, is made to live in a community, in a union of persons; and the greatest union is that of marriage, when two become one flesh.

This notion of man made for fellowship with God and his fellow human beings is summed up in biblical language as man made ‘in the image and likeness of God’. The majority of the Greek Fathers state that ‘image’ and ‘likeness’ are not one and the same thing. The image indicates freedom and reason, while the likeness indicates assimilation to God. In short: we become like God by making the right use of our freedom and reason. This is why the Church believes so strongly in free will. Without it, we are no more accountable for our actions than animals, and can never come into union with God. If God is love, then God is also freedom, because love is something that can only be freely given; it cannot be forced. Love, as the Church understands it, is not an instinct; it is not implanted in us by nature. We love because we choose to.

If the likeness of God is something that man had to obtain through correct use of God’s image, then it means that man had to develop. He was made perfect in the sense that he was flawless and sinless, but he had yet to attain full union with God. The likeness of God was something that man was given the potential of achieving through God’s grace and providence and man’s free will together. (Things fell to pieces when man made wrong use of his freedom). And so, when God created man, he also gave man his share of the work. Man was not made to lounge around in an idyllic paradise eating strawberries: he had work to do. But what was the nature of this work? To explain this, I would like to draw your attention to Genesis 2: 15:

‘And the Lord took the man, and put him into the garden of Eden to work it and to keep it’.

Many commentators interpret this work in terms of the cultivation of agriculture: farming or gardening. But what is interesting is that, in the Hebrew, the same vocabulary – ‘work’ and ‘keep’ – is used to describe the priestly responsibilities of the tabernacle, or temple, in the Book of Numbers:

‘They shall keep guard over him… before the tent of meeting, as they work (minister) at the tabernacle’. (Num. 3: 5-7)

This is the only other time in the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Old Testament) that the Hebrew verbs in Genesis 2:15 for ‘work’ and ‘keep’ are used – in describing the Levites’ priestly duties guarding and ministering in the Sanctuary.

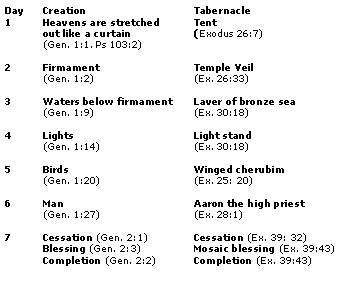

In this connection, it is worth noting the comparison made by Rabbinic interpreters between the description of the 7 days of Creation in Genesis and the description of the construction of the tabernacle, or temple, in the Book of Exodus:

In this connection, it is worth noting the comparison made by Rabbinic interpreters between the description of the 7 days of Creation in Genesis and the description of the construction of the tabernacle, or temple, in the Book of Exodus:

In Genesis, it is written: ‘In the beginning God created the heaven’, and in psalm 103: ‘who stretches out the heaven like a curtain’; while of the tabernacle, in the Book of Exodus, it is written: ‘And you shall make curtains of goat’s hair for a tent over the tabernacle’. Of the second day of creation we read: ‘Let there be a firmament … and let it divide the waters from the waters’; and of the tabernacle: ‘The veil shall divide the holy place from the holy of holies’; of the third day of creation: ‘Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together’; and of the tabernacle: ‘You shall make a laver of brass… whereat to wash’. Of the fourth day it is written: ‘Let there be lights in the firmament of heaven’; and of the tabernacle: ‘You shall make a candlestick of pure gold’. Of the fifth day of creation: ‘Let foul fly above the earth’; of the tabernacle: ‘The cherubim shall spread out their wings’. On the sixth day man was created; and in connection with tabernacle it says: ‘Bring near unto you Aaron your brother’ (Aaron being the high priest). On the seventh day we have: ‘And the heaven and the earth were finished’, ‘God blessed and hallowed’, and ‘on the seventh day God finished the work which he had done’; and of the tabernacle it is written: ‘Thus was finished all the work of the tabernacle’, ‘And Moses blessed them’, ‘And it came to pass on that day that Moses made an end’.

These tabernacle-creation parallels mean that, if the creation is God’s ‘cosmic temple’, then the garden of Eden is the first holy of holies – the first altar or sanctuary – and Adam is the first priest. Read within the greater context of scripture, Adam’s responsibilities in the garden of Eden are primarily priestly, not agricultural.

So, man’s primary task and purpose in paradise was a priestly one. But to have a better understanding of what this means, we need to consider what the priest’s main task and purpose is. The priest’s key role is to celebrate the sacraments, and the main characteristic of a sacrament is that man takes natural material (bread, water, wine, oil) and offers it back to God in thanksgiving, while asking Him to make it a means of imparting His grace and mercy to us. Man, as priest of creation, is not called to dominate creation, nor even to merely take care of it, but to offer it back to God. In this way, creation becomes far more than the means of man’s sustenance; it becomes a means of thanksgiving, blessing, sanctification and salvation. Furthermore, man does not simply use raw materials; he uses his creative powers to fashion them into something different to what they were at first. The greatest example of this is the Eucharist, which means ‘thanksgiving’. At the Eucharist, we do not offer wheat and grapes, but bread and wine. Man takes God’s creation, makes something out of it, and gives it back to God; and God, in turn, sanctifies it. Man makes the bread and wine from the materials God has given him, offers what he has made to God, and God transforms it into the Body and Blood of Christ for the forgiveness of sins and eternal life. And this act of offering creation back to the Creator is expressed above all in the prayer of the anaphora at the Divine Liturgy: ‘Offering you your own of your own, in all things and for all things, we praise you, we bless you, we give thanks to you, O Lord, and we pray to you, our God’. And so, it is above all at the Divine Liturgy that we truly fulfil our calling as ‘sacramental beings’.

Bearing this sacramental purpose of man in mind, the creation of Eve as Adam’s ‘helper’ must also be seen in a sacramental light. The purpose of Eve in relation to Adam is all too often viewed in terms of procreation, but this is not actually the main purpose of Eve; she was created to assist Adam in his priestly duties. She was not made to simply bear children or to be the servant of man, and she was certainly not created to be chained to the kitchen sink, but to participate as a helper in man’s sacramental purpose in life. Of course, this does not exclude child-birth. If, as I said, the key characteristic of sacrament is offering God’s creation back to the Creator, then child-birth is the greatest sacrament: the offering of another human life to God for Him to consecrate it, hallow it and transfigure it by His grace. But woman’s role in procreation must always be seen in sacramental terms, because Eve’s role as a helper is directly connected to Adam’s role as a priest. Man can not carry out his sacramental role without the assistance of woman.

It is no coincidence, given that man before the fall was made for priestly work, that in the last book of the Bible, the Book of Revelations, redeemed humanity is described as carrying out the same work:

“Blessed and holy are they who have a part in the first resurrection… they will be priests of God and of Christ and will reign with Him for a thousand years”. (Rev. 20:6).

“You were slain and by your blood you ransomed for God saints from every tribe and language and people and nation; you made them to be a kingdom and priests serving our God, and they will reign on the earth”. (Rev. 5: 9-10).

“To him who loves us and freed us from our sins by his blood, and made us to be a kingdom, priests serving his God and Father, to him be glory and dominion forever and ever”. (Rev. 1: 5-6)

Bearing all of this in mind, whenever we read Genesis, and the scriptures in general, we should always be aware that we must read it within the greater context of scripture. When we read the Old Testament, we must read it in the light of the New Testament, which shows us the true meaning of the symbolism, imagery, history, poetry and prophecies of the Old Testament. This is particularly true of Genesis. We have to look beyond the imagery and simple language of Genesis, which all too often hinder us from perceiving its fundamental message: that man was made by God to worship Him, to make good use of the Image of God in man, to make something of God’s creation and give it back to Him in praise and thanksgiving, in order that He in turn may impart to us His Divine Grace which transforms us into God’s likeness. In short: the message of Genesis is that God made man to be priest of creation.

————————–

Notes

1 Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, vol. 1, ed. Jaroslav Pelikan (St Louis: Concordia, 1958, p.3)

2 Severianos of Gabbala, On The Creation Of the World. Quoted in a lecture at the Ian Ramsey Centre, Oxford, Theology and Science, by Archbishop Gregorios of Thyateira & Great Britain, published in The Orthodox Herald, Issue 206-207, Nov/Dec 2005.

3 Origen, On First Principles. Quoted in a lecture at the Ian Ramsey Centre, Oxford, Theology and Science, by Archbishop Gregorios of Thyateira & Great Britain, published in The Orthodox Herald, Issue 206-207, Nov/Dec 2005.