I spent ten days on pilgrimage in the Holy Land. (That’s right! You can call me Elissa Hadzi-Bjeletich now!) As they say, we walked in Christ’s footsteps; we touched the stones that He touched. Again and again, we said to ourselves, This is where it happened. Right here on this spot.

As I prepared to embark on this pilgrimage, I thought a lot about what that means. God is everywhere; He is ever-present so He is right here in Texas, and I need not travel across the globe to find Him. As He told the Samaritan woman, we don’t have to go to the Temple or to the top of a mountain; we worship in spirit and in truth. He is with us always. We can find Him wherever we are.

Why walk where He walked? What did I expect to happen there? What did I hope to see? I wasn’t sure, and I held on to a conviction that it is better not to have expectations, but instead to simply show up open, to be ready to receive whatever the Holy Spirit sends to me. I thought, God knows what I need better than I do, so I will make this effort, and I will trust that He sees my effort and my ready, open heart, and He will send what is best.

And then I found myself in Galilee, waking up to a beautiful morning in Nazareth. As we journeyed around to our first holy sites, my brain strained to wrap itself around the idea that these are the landscapes He saw, these are the steps my Lord walked. I strained to know this truth, and to understand what the implications of this truth might be. Entering this Holy Land was like entering a church in a bustling city — it took me a while to let my brain settle down, to allow the peace to settle in. And then I could feel it. I was in a holy place. This is the place where He called His disciples, where they fished on the Sea of Galilee and preached on its shores. I was impressed with the beauty of God’s choice. He picked a lovely spot for His ministry on earth.

We slowly made our way to Jerusalem. We visited churches where monks have been recently martyred as they protected the holy site; we met Christians who witness to the Resurrection amid opposition and oppression. We saw Christ in His Saints, alive and present and real.

We visited the prison cell of St. John the Forerunner, venerated the relics of the Holy Innocents, and kissed the rocks on which St. Stephen gave up his soul to become the first martyr. We venerated the very spot where Archangel Gabriel greeted sweet Mary and announced that she would conceive God. We touched the spot where our Lord burst into this world. We prayed in the places where He taught and performed miracles. We touched the rock on which Christ entered into the grief of Martha and Mary and wept with them, and then we stood in the tomb of Lazarus, and listened for Christ’s call, “Come out!” We entered into the prison where they put our Lord Jesus Christ into stocks, where they beat Him and mocked Him, and where He awaited his death. We placed our hands in the hole in the stone where the cross stood as He gave up His life, and in the cracks left by the quaking of the earth as it saw its Creator enter into Hades. We lay our heads on the stone where Christ lay dead, and then as only God could do, resurrected and trampled down death by His death.

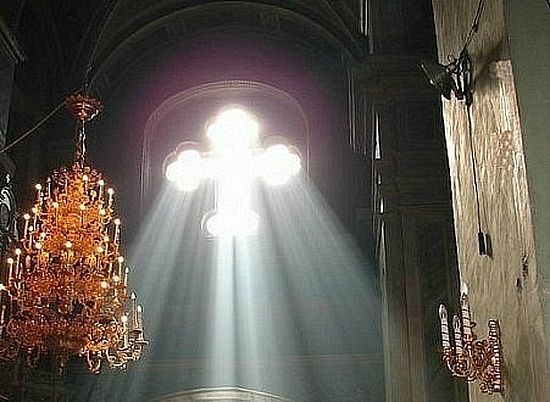

These are the most central and important events in the life of the world, and they happened at a specific moment and in a specific place. Somehow, we enter into those moments mystically again and again — they have a life beyond that time and space — but there is also something mystical and powerful about being in the place where it happened. Archbishop Theophanis of Jerusalem would say to us again and again, “This is the epicenter of the universe.” This is the epicenter. It is. You can feel it.

This is where it happened.

When I thought of the Incarnation, I have always thought about how God took on flesh. He could not be harmed and He could feel neither cold nor hunger, but He chose to become subject to all those miseries when He humbled Himself and showed up here, on this earth, as a tiny baby in the arms of a young holy virgin. When I thought of the Incarnation, I thought of Christ’s human body.

But in the Holy Land, I began to understand that the Incarnation means more than that. It means that Christ entered into time and space. Yes, He sanctified the waters of the Jordan when He was baptized, but He also sanctified these lands when He walked on them, when He suffered and bled on them.

God didn’t have to take on a body. He didn’t need one. We needed Him to take on a body — to stand with us on this actual earth, to speak with us, to enter into Hades and break open the gates of Paradise for us.

We need a Holy Land too. We need holy places. It’s not that God needs to occupy to specific points on this earth, but it’s that we need to make our offering of pilgrimage. We need to see and to touch. We need to travel to our churches on Sunday mornings, and to go visit monasteries and to venerate myrrh-streaming icons. We need to make an effort, to engage in a struggle, so that we can feel ourselves coming towards God on this human journey. Our journey is not just spiritual — it’s physical too; it happens in time and space. We benefit from the action of making a pilgrimage. We need it.

So many of the holy places preserved in Israel and Palestine are in caves, and it struck me that God wisely chose a land built on rock, so that holy places would be dug down and carved into stone. He chose a place where even after waves of conquerors and invaders, after the buildings and the churches were destroyed and in ruins, the caves would remain so that we would have holy places to visit. He knew.

On my final day in the Holy Land, I venerated the Anointing Stone at the Holy Sepulchre, saying goodbye as it were to God’s holy places. I thanked Him for the fullness of His Incarnation, for leaving us these places and being so present in them, so that we could pursue our spiritual journey in such a tangible way. And as I arrived home, I thanked Him for being here too, ever-present and filling all things.

Great Lent it already upon us, and this weekend we celebrate the Sunday of Orthodoxy. When the veneration of icons was challenged and attacked, when Christians were dying to protect their beloved holy icons, the tide was turned by the understanding that Christ became man, that He took on flesh, so that He could be seen and touched — and painted. We can make images of Him, because we know what He looks like. He took on a particular material reality. Icons testify to the Incarnation in a profound way: they say, “Look! This our God who took on flesh.”

God knows that we live as soul and body, as spirit and matter. He came to live this way with us too. He knows that we need those physical manifestations of our spiritual worship — the icons, the pilgrimage, the Holy Communion, the lighting of candles and the sign of the cross. We need to make our spiritual understanding a material reality.

Blessed Lent!