My bishop is probably not going to believe this.

Recently, a member of our congregation was very upset. She heard that the new priest was planning to cremate a young couple, right there in church, on the solea, during Great Vespers on the next Saturday night.

“Doesn’t the Orthodox Church forbid cremation?” she asked her friends. No one had ever heard of such a thing. Exciting gossip began to make the rounds during coffee hour.

No wonder she was concerned. This particular young couple was very promising. Charming and intelligent, they had come to us especially looking for an Orthodox church in the area. Although both had been baptized, they were reared without any particular faith; the young man’s parents were atheist, as was the woman’s mother until recently. Now they had decided to become Orthodox Christians, and to be married sacramentally in the Church. They had their whole life ahead of them…until now.

Fortunately, before the gossip could spread very far, one of our members pointed out a solution: cremation, which is indeed forbidden to Orthodox Christians, is not the same thing as chrismation, which is what the priest was about to do with this young couple. One is at the end of life; the other one is at the beginning.

The cremation/chrismation confusion may have just been a problem of translating English to Greek. However, it may also have been because, in this particular congregation, there have not been very many converts who were chrismated until recently. Either way, on the chance that there might be another Orthodox Christian in America who does not know the difference between these two things, it seems like a good idea to explain what they are and why we do, or do not, practice them.

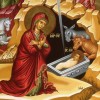

Chrismation

Let’s start with chrismation. This word refers to Holy Chrism, which is blessed oil. To “chrismate” someone is to anoint him or her with oil while praying for the gift of the Holy Spirit. The words “chrism” and “chrismate” come from the Greek word chrisma, “oil for anointing.”

The oil itself is also called myron (similar to the word, “myrrh”), which is borrowed from a Semitic word for sweet-smelling ointment. It is a special oil—said to be made of over forty sweet-smelling fragrances mixed with purest olive oil—which is blessed by the Patriarch. In the Greek Orthodox churches, this is the Ecumenical Patriarch, who prepares the myron at the Phanar in Constantinople (Istanbul) following an ancient recipe.

Chrismation immediately follows baptism. It is the Mystery (or “sacrament”) of the Church which admits us to Holy Communion. Using the myron, the priest anoints the newly-baptized person’s face, chest, hands, back of the neck, and feet.

In the ancient Church, baptism and chrismation were performed together. Chrismation is mentioned by some of the earliest writers of the church; it is described, for example, in The Apostolic Tradition compiled by Hippolytus in the third century. With chrismation, we become ministers in the Church of God.

The oil of chrismation should not be confused with the “oil of blessing” which is used just before baptism in Orthodox churches. The use of oil before baptism is also very ancient, described by St Hippolytus as the “oil of exorcism.” The blessing-oil is olive oil (not myron) which is poured into the baptismal waters and into the hands of the sponsor. Then the oil is poured over the whole body of the person who is about to be baptized. It symbolizes protection against evil, as well as the abundant blessings of God. At this point in the baptismal rite, the prayers remind us that God gave Noah a branch of olive as the first gift after the Flood, to be the first planting in the new land.

Roman Catholic and many Protestant Christians still practice a remnant of the Orthodox sacrament of chrismation. In those traditions it is called “confirmation.” In the West, however, chrismation/confirmation became completely separated from baptism. This was because, in Roman practice, only a bishop could chrismate (“confirm”). Since bishops were often located far from individual churches, it sometimes took a very long time—perhaps years—for the bishop to visit a congregation. Eventually, this became the norm in the western churches.

Today in the Roman Catholic communion and in some Protestant churches (such as Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist and Church of Christ), confirmation is reserved for young teens or adults after a period of instruction. However, Protestants do not regard confirmation as a sacrament, and anointing with oil has disappeared. Its significance has also changed. In more recent times, younger children (usually seven or eight years old) have been allowed to receive their “first communion;” and most Protestants allow virtually anyone to participate in Holy Communion. Thus, in the West, chrismation/confirmation is no longer seen as the beginning of Christian life. Rather, it is a kind of “graduation” into adult life after studying about the faith.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, chrismation was never separated from baptism. The local priest both baptizes and chrismates a catechumen (“one who is taught”), who then receives Communion. This is true even for infants. Just as for baptism, the emphasis is upon what God does, rather than upon what the catechumen believes. It is the beginning of life; therefore, we do not wait for it. After chrismation, it is assumed that the family and sponsor(s) will bring the child to church and faithfully teach him or her the faith and the practices of the Church, including fasting and coming to Confession.

Today, many adults are choosing to become Orthodox Christians. If they were baptized before in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, most American Orthodox churches do not re-baptize them. Rather, after a period of instruction (usually at least a year), the catechumens confess the Orthodox faith before the congregation, are chrismated, and then admitted to Holy Communion.

Cremation

Cremation is something else altogether. This term comes from Latin cremare, which means to dispose of a corpse by burning it. Orthodox Christians bury the dead; we do not burn them.

In pre-Christian times, some cultures burned their dead, and others buried them. Greeks and Romans generally preferred burial, but there were funeral pyres, too (piles of wood on which the body was placed, to be burned).

Jews felt that the human body should be respected as the image of God. Therefore, the body was first carefully washed and then placed in a shroud for burial. After a period of time, the bones were dug up, washed in wine and placed in a “bone-box” called an ossuary. Many of these ancient stone ossuaries have been found in the Holy Land. It was common for families to carry the relics of their ancestors around with them.

The practice of burning the dead dates to pre-historic times and was found throughout Europe and Britain in Roman times. Most of us have seen re-enactments in movies of a Scandinavian practice: Vikings placed a body in a boat, which was then set afire and sent out to sea. However, this practice would have been too expensive for ordinary people, and was probably reserved for rulers and special warriors.

Cremation is universally practiced by Hindus in India, and by most Buddhists. Hindus place the body on an elaborate funeral-pyre outdoors, but in Asia modern Buddhists usually rely upon funeral homes to do the cremating. Among many Buddhists, paper “clothing” and other items, such as paper automobiles and models of houses, are burned along with the dead to insure that they will have all that they need in the after-life. However, it is also the practice of some Asians to bury the dead and, like the Jews and Christians of ancient times, to exhume the body after a period of time, wash the bones, and place them in an urn.

Until recently, in many Native American cultures the dead were placed on a high scaffold. This practice may have stemmed from pre-historic practices in Siberia and Mongolia. There, perma-frost prevents easy burial in the ground. For the same reason, one of the most unusual practices today is found in Tibet. In the so-called “sky-burial,” the body is taken to a high mountain-top, cut into pieces and then fed to eagles.

In America today, cremation is growing in popularity. Many families do not request a funeral or burial service, but instead have a memorial service (or “celebration of life”) after the cremation has taken place. There seem to be two reasons for this. One is that it is less expensive than burial through a funeral home. Another reason may be that increasingly, young Americans profess to have no religious views at all. Therefore the concept of the body as the image of God, deserving special care, has no particular meaning.

Orthodox Christians do not cremate the dead, ever. First, we are taught to respect the integrity of the body. This was much more obvious years ago, when the body of a relative would be carefully washed at home, and then wrapped in a shroud or dressed for burial. The point was to care for the body even in death.

Another reason is that in our Orthodox Christian faith, we see the body as the Temple of God. It is not to be destroyed (cf. 1 Corinthians 3:17, where St. Paul says that “if anyone destroys God’s temple [i.e. the body], God will destroy him”). For the same reason Orthodoxy opposes abortion, the death penalty, drug use, tattooing, piercing the body, or other forms of bodily desecration. Of course, if a person’s body were to be destroyed by earthquake or fire, or an airplane or car crash or other accident, we do not believe that the person cannot be resurrected on the Last Day. But we do not deliberately destroy the body.

In conclusion, if you hear that an Orthodox priest is about to cremate someone, do not believe it. The Orthodox Church does not even allow a priest to conduct an Orthodox funeral for anyone whose body is going to be cremated. This is for the obvious reason that the Orthodox funeral is actually a burial service, not a “memorial” as is so often seen today in American culture. Only pious Orthodox Christians who have been communicants may be buried in the Orthodox Church.

If, on the other hand, you hear that someone is about to be chrismated, celebrate! Welcome the newly baptized and enlightened person into the Body of Christ. Oh, and a parting word of advice: don’t listen to gossip. Just sayin’.