Without confession, love is destroyed.

It is impossible to imagine a vital marriage or deep friendship without confession and forgiveness. If you have done something that damages a relationship, confession is essential to its restoration. For the sake of that bond, you confess what you’ve done, you apologize, and you promise not to do it again.

In the context of religious life, confession is what we do to safeguard and renew our relationship with God whenever it is damaged. Confession restores our communion with God.

The purpose of confession is not to have one’s sins dismissed as non-sins but to be forgiven and restored to communion. As the Evangelist John wrote: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just, and will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.” (1 Jn 1:9) The apostle James wrote in a similar vein: “Therefore confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another, that you may be healed.” (Jas 5:16)

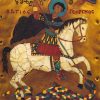

Confession is more than disclosure of sin. It also involves praise of God and profession of faith. Without the second and third elements, the first is pointless. To the extent we deny God, we reduce ourselves to accidental beings on a temporary planet in a random universe expanding into nowhere. To the extent we have a sense of the existence of God, we discover creation confessing God’s being and see all beauty as a confession of God. “The world will be saved by beauty,” Dostoevsky declared. We discover that faith is not so much something we have as something we experience — and we confess that experience much as glass confesses light. The Church calls certain saints “confessors” because they confessed their faith in periods of persecution even though they did not suffer martyrdom as a result. In dark, fear-ridden times, the faith shone through martyrs and confessors, giving courage to others.

In his autobiography, Confessions, Saint Augustine drew on all three senses of the word. He confessed certain sins, chiefly those that revealed the process that had brought him to baptism and made him a disciple of Christ and member of the Church. He confessed his faith. His book as a whole is a work of praise, a confession of God’s love.

But it is the word’s first meaning — confession of sins — that is usually the most difficult. It is never easy admitting to doing something you regret and are ashamed of, an act you attempted to keep secret or denied doing or tried to blame on someone else, perhaps arguing — to yourself as much as to others — that it wasn’t actually a sin at all, or wasn’t nearly as bad as some people might claim. In the hard labor of growing up, one of the most agonizing tasks is becoming capable of saying, “I’m sorry.”

Yet we are designed for confession. Secrets in general are hard to keep, but unconfessed sins not only never go away but have a way of becoming heavier as time passes — the greater the sin, the heavier the burden. Confession is the only solution.

To understand confession in its sacramental sense, one first has to grapple with a few basic questions: Why is the Church involved in forgiving sins? Is priest-witnessed confession really needed? Why confess at all to any human being? In fact, why bother confessing to God even without a human witness? If God is really all-knowing, then he knows everything about me already. My sins are known before it even crosses my mind to confess them. Why bother telling God what God already knows?

Yes, truly God knows. My confession can never be as complete or revealing as God’s knowledge of me and all that needs repairing in my life.

A related question we need to consider has to do with our basic design as social beings. Why am I so willing to connect with others in every other area of life, yet not in this? Why is it that I look so hard for excuses, even for theological rationales, not to confess? Why do I try so hard to explain away my sins until I’ve decided either they’re not so bad or might even be seen as acts of virtue? Why is it that I find it so easy to commit sins yet am so reluctant, in the presence of another, to admit to having done so?

We are social beings. The individual as autonomous unit is a delusion. The Marlboro Man — the person without community, parents, spouse, or children — exists only on billboards. The individual is someone who has lost a sense of connection to others or attempts to exist in opposition to others — while the person exists in communion with other persons. At a conference of Orthodox Christians in France not long ago, in a discussion of the problem of individualism, a theologian confessed, “When I am in my car, I am an individual, but when I get out, I am a person again.”

We are social beings. The language we speak connects us to those around us. The food I eat was grown by others. The skills passed on to me have slowly been developed in the course of hundreds of generations. The air I breathe and the water I drink is not for my exclusive use but has been in many bodies before mine. The place I live, the tools I use, and the paper I write on were made by many hands. I am not my own doctor or dentist or banker. To the extent I disconnect myself from others, I am in danger. Alone I die, and soon. To be in communion with others is life.

Because we are social beings, confession in church does not take the place of confession to those we have sinned against. An essential element of confession is doing all I can to set right what I did wrong. If I stole something, it must be returned or paid for. If I lied to anyone, I must tell that person the truth. If I was angry without good reason, I must apologize. I must seek forgiveness not only from God but from those whom I have wronged or harmed.

We are also verbal beings. Words provide not only a way of communicating with others but even with ourselves. The fact that confession is witnessed forces me to put into words all those ways, minor and major, in which I live as if there were no God and no commandment to love. A thought that is concealed has great power over us.

Confessing sins, or even temptations, makes us better able to resist. The underlying principle is described in one of the collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers, the Gerontikon:

“If impure thoughts trouble you, do not hide them, but tell them at once to your spiritual father and condemn them. The more a person conceals his thoughts, the more they multiply and gain strength. But an evil thought, when revealed, is immediately destroyed. If you hide things, they have great power over you, but if you could only speak of them before God, in the presence of another, then they will often wither away, and lose their power.”

Confessing to anyone, even a bartender, taxicab driver or stranger in an airport, renews rather than contracts my humanity, even if all I get in return for my confession is the well-worn remark, “Oh that’s not so bad. After all, you’re only human” — something like the New Yorker cartoon in which a psychologist reassures a Mafia contract killer stretched out on the couch, “Just because you do bad things doesn’t mean you’re bad.”

But if I can confess to anyone anywhere, why confess in church in the presence of a priest? It’s not a small question in societies in which the phrase “institutionalized religion” is so often used, the implicit message being that religious institutions necessarily impede or undermine religious life. Yet it’s not a term we seem inclined to adapt to other contexts. Few people would prefer we got rid of institutionalized health care or envision a world without institutionalized transportation. Whatever we do that involves more than a few people requires structures.

Confession is a Christian ritual with a communal character. Confession in the church differs from confession in your living room in the same way that getting married in church differs from simply living together. The communal aspect of the event tends to safeguard it, solidify it, and call everyone to account — those doing the ritual, and those witnessing it.

In the social structure of the Church, a huge network of local communities is held together in unity, each community helping the others and all sharing a common task while each provides a specific place to recognize and bless the main events in life from birth to burial. Confession is an essential part of that continuum. My confession is an act of reconnection with God and with all the people and creatures who depend on me and have been harmed by my failings and from whom I have distanced myself through acts of non-communion. The community is represented by the person hearing my confession, an ordained priest delegated to serve as Christ’s witness, who provides guidance and wisdom that helps each penitent overcome attitudes and habits that take us off course, who declares forgiveness and restores us to communion. In this way our repentance is brought into the community that has been damaged by our sins — a private event in a public context.

“It’s a fact,” writes Fr. Thomas Hopko, “that we cannot see the true ugliness and hideousness of our sins until we see them in the mind and heart of the other to whom we have confessed.”

This is an extract from Confession: Doorway to Forgiveness (Orbis Books, 2002). Jim Forest’s earlier books include Praying with Icons, Ladder of the Beatitudes as well as biographies of Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

Source: In Communion