Living the Christian faith is based on a practice of solitude, a spirit of stillness, a pedagogy of experience, and victory through suffering.

Living the Christian faith is based on a practice of solitude, a spirit of stillness, a pedagogy of experience, and victory through suffering.

For some Christians these ideas are at best outdated, and at worst nonsense. The popular vibe given off by many today is that Christianity is something like an ongoing victory lap of a battle we never fought, a battle we never needed to fight, because Christ paid the price of suffering in our place. Our task is to simply bask in the blessings and try not to get fat.

It’s an appealing notion, particularly when decades of peace and prosperity pass without any serious interruption: no pandemics, no homeland war, no stock market crashes, no widespread starvation, etc. In general (barring personal health issues) the most one has to worry about in a place like the USA is keeping up with the prosperity of one’s neighbor. In this culture the proof of blessedness is not who can endure the most suffering, but rather who can avoid the most suffering.

It is not uncommon to hear Christians blame hardship on lack of faith. They often point to Christ as the ultimate example of a life lived in abundance and health – He promises to “give life, and life more abundantly.” Therefore, if one’s life is full of troubles it must be due to lack of faith.

If this mindset is not put into a fuller context, it seems to require either a strategic denial or total ignorance of what Christ meant by “Carry your cross and follow Me,” along with the added promises of trials and persecutions for living righteously.

For many of us, the coronavirus is the first encounter we’ve had with an immediate, worldwide, existential threat; a threat large enough to reveal the actual frailty of mankind. Many are discovering for the first-time that death and calamity are possible even though Christ suffered in our place. This is sad considering that Christians should be the ones most acquainted with real life, with the true nature of our being in the world.

One often hears the atheist mock Christianity as a crutch for the weak, a comfort for the intellectually challenged; that Christians believe in fairytales, and live in a phantasmal alternate reality. Remove the true heart of Christianity and this mocking is absolutely true. If one believes that Christianity is a bailout from suffering and moral vigilance, an everlasting spiritual cocktail party, or a mere Sunday morning changing of the guard, then one does in fact believe in fairytales. Christianity is and always has been a path of solitude, stillness, experience, and suffering – in the best way possible.

Solitude

Whether one goes back to the life of Abraham and his journey out of his homeland, to Moses and his 40 years in the desert, to Elijah and Elisha and their ascetic solitude on Mt. Carmel, to John the Baptist and his living on locus and honey in the wilderness, or any number of the Holy Fathers and their lives of asceticism, one quickly realizes that solitude and the faith are blood brothers from beginning to end.

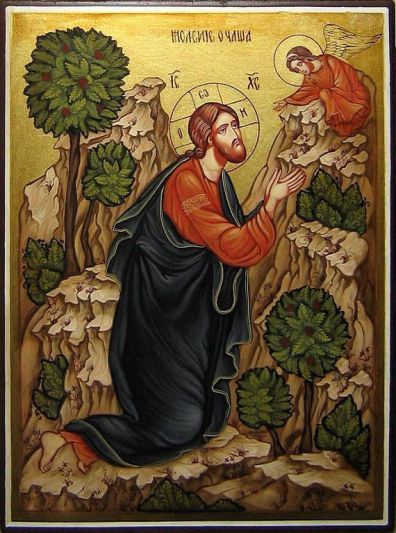

Christ set the standard of solitude not only during his temptation, but in his regular daily life, often spending entire evenings alone in prayer. One easily recalls that just before His passion Christ prayed alone for several hours, outlasting his most devout and strong-willed disciples. When Christ’s disciples failed to cast out demons, Christ instructed them that “this kind comes out only by prayer and fasting.”

A believer who has not made a compact with solitude will likely never encounter the genuine faith experienced by Christ’s flock throughout the ages. The state of affairs in the world right now provide almost a forced opportunity to have this encounter, but one must use it intentionally and avoid common distractions when the inevitable boredom sets in.

Stillness

Stillness, and its twin brother watchfulness, is the result of solitude rightly used. Stillness, as defined by the Orthodox tradition, is the inner state of “tranquility or mental quietude and concentration which arises in conjunction with, and deepened by, the practice of pure prayer and the guarding of the heart and intellect. Not simply silence, but an attitude of listening to God and of openness towards Him” (Greek Philokalia).

So critical is stillness and watchfulness that Christ Himself demonstrated its necessity during His trial in the wilderness. Unlike Adam who used his solitude unwisely, Christ used His solitude to cultivate stillness, which allowed Him to defeat every temptation of the Devil. Christ did not simply call down majestic powers from on high, rather He endured every demonic trick through vigilant watchfulness and prayer.

Experience

The Christian faith is not a simple set of doctrines, an objective check lists of orthodoxy and heterodoxy, or a spiritual science. The faith is an entering into; it is a participation, a “partaking of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:5). And there is only one way to partake of God’s nature – by being present. One cannot partake of God through mere cognitions, through analyzing abstract concepts of God, or by fixing one’s mind in the past or future. The partaking is only possible in the experience of now. Who ever heard of filling one’s stomach on the idea of a sandwich, or warming oneself by a concept of fire? Just as breath is only taken in the present, partaking of God requires the sort of presentness which only solitude and stillness can grant.

Suffering

Perhaps one of the most misunderstood aspect of the faith today has to do with suffering. What is a modern Christian, conditioned by scientific mastery of nature and instant gratification, to do with a faith that not only does not alleviate the kind of suffering that comes by living righteously, but rather encourages it? One has two options: (a) deny suffering and develop a doctrine that promises the opposite, or (b) cherish it as a means of salvation. This latter idea is so far outside the realm of acceptance today that many consider it proof of a mental disorder.

But without this view of suffering the true faith is lost. The Apostle Peter understood that a believer was perfected, established and strengthened by “suffering a while” (1 Pet 5:10-11); that one’s faith was “made genuine” and “more precious than gold” due to being “grieved by various trials” (1 Pet 1:6-11). Peter believed that one should rejoice “to the extent that you partake of Christ’s sufferings” as evidence that the “Spirit of glory and of God rests upon you” (1 Pet 4:12-14).

The Apostle Paul boasted that he boasted in nothing but the “fellowship of His (Christ’s) sufferings, being conformed to His death” and suffering the “loss of all things” (Phil 3:8-15). And of course, the writer of Hebrews teaches that Christ Himself was “perfected through sufferings” (Heb 2:9-11).

This is but a small sample of Scriptural teaching on suffering, and beyond Scripture there is truly endless teaching and examples from the Holy Fathers.

If one thinks of it in terms of athletics, who would discount the necessity of suffering? What athlete bemoans a hard workout, the strain, the testing of the muscles and the soreness it produces? An athlete understands that the more he or she breaks down a muscle and builds it up, breaks it down and builds it up again, and again, the stronger they will become – the more likely they will win the prize. The suffering endured during the body’s development is understood as the production of strength for the serious athlete. This is of course why St. Paul uses athletics as an illustration of the spiritual life.

Again, the coronavirus has forced the world into a mode of isolation. Isolation can be scary and has its natural torments (why else do we use isolation to punish criminals?), but turning isolation into solitude is a simple adjustment of perspective. And since much of the faith is inaccessible without solitude, this adjustment could result in a wonderful awakening for many children of God.