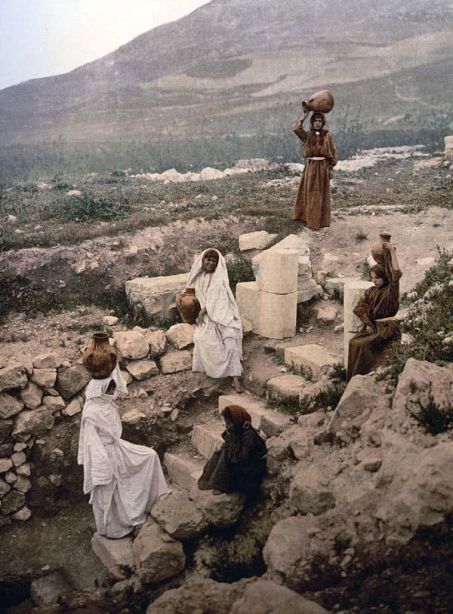

We see Christ speaking with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s Well, on the road from Jerusalem to Galilee. Samaria is located between the two; the road that goes through it is the shortest, but Jews normally avoided going this way, instead bypassing it through the Jordan Valley.

Exactly the same thing takes place now: to drive in cars with Israeli numbers through the territory of the Palestinian Authority, to which Samaria belongs, is not without danger. The Samaritans, just as thousands of years ago, still slaughter a Passover lamb on Mount Gerizim and read the very same Torah in ancient Hebrew. If one does not notice the conveniences ushered in by technological progress – used by both the Bedouins of the desert and the Aborigines of Australia – a traveler finding himself in Samaria during Passover will feel transported back to Biblical times before the Nativity of Christ, times when the division between the Samaritans and Jews took place.

This occurred when the Jews, having returned from the Babylonian captivity, found the central territory of their country occupied by a people that had arisen from the mingling of Jews and pagans and that professed Judaism in a quite peculiar manner. The Samaritans, who considered themselves the true descendants of Abraham, were not pleased by the Jews’ return from Babylon, just as they were not pleased by the reconstruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. They believed that it was more proper to worship God on Mount Gerizim than on Mount Sion, as the Samaritan woman recalls when speaking with the Savior. It is to this conversation that we now turn.

Then, writes the Evangelist John, cometh He to a city of Samaria, which is called Sychar, near to the parcel of ground that Jacob gave to his son Joseph. Now Jacob’s well was there. Jesus therefore, being wearied with his journey, sat thus on the well: and it was about the sixth hour. There cometh a woman of Samaria to draw water. For us there is nothing strange in this. But any resident of the Middle East would be puzzled by this appearance. This is the hottest time of the day, time for the afternoon rest. Girls and women of the East do not go to wells in broad daylight; they prefer the morning and evening hours. The fact that this woman comes for water in the scorching heat shows that she has reasons not to meet with her fellow villagers; what follows will clarify why. Moreover, from the perspective of an Eastern person, a person of patriarchal culture, something even stranger takes place: Jesus saith unto her, Give me to drink. (For His disciples were gone away unto the city to buy food.) Then saith the woman of Samaria unto Him, How is it that Thou, being a Jew, askest drink of me, which am a woman of Samaria? for the Jews have no dealings with the Samaritans.

Jesus, Whom she recognized as a pilgrim to Jerusalem, does not have a pitcher with which to draw water; the Samaritan woman does has one – but she is a Samaritan.

No self-respecting Jew would turn to her with such a request: Jews neither eat nor drink with Samaritans, just as they neither eat nor drink with pagans and obvious sinners, not using common dishes with them (just like the Kerzhak Old Ritualists with “Nikonians”): for them this is defilement and almost a betrayal of the God of Israel.

Sharing a table with pagans and the impious means that one becomes pagan and impious oneself. We find an echo of this in an epistle of the Apostle Paul in which he forbids Christians from eating with people who, calling themselves brethren (i.e., Christians), lead a dissolute life. There is yet another factor: in keeping with the generally accepted norms of religious morality, a man will never speak with a woman in the absence of her husband, to whom her soul and body belong as his property. Therefore, even the disciples of Jesus, when they had returned with their provisions, were rooted to the ground when they saw their Teacher speaking with a woman – and, what is more, a Samaritan. The woman, too, was surprised. Although the answer is simple.

Anyone who has been to Israel will know that the climate is such that, if one does not continually drink water, serious health problems – not excluding death – can arise at any moment from the body’s lack of water. That is, one can literally die of thirst. However, Jesus does not say anything about His own thirst; on the contrary, it is she, the Samaritan, who should have asked Him for water: Jesus answered and said unto her, If thou knewest the gift of God, and Who it is that saith to thee, Give Me to drink; thou wouldst have asked of Him, and He would have given thee living water.

It seems as though His request was just a pretext for starting a conversation. Something drew Him to this woman appearing at the well at an inopportune time. Jesus undoubtedly saw what He would later speak of, when addressing His interlocutor’s difficult “life circumstances.” In other words, seeing this inhabitant of a Jewish-hostile town approaching the well, He decided to help her. Which He began to do immediately, by speaking about the most important thing: living water.

We know that He is not investing this term with what was normally understood to be living water: running water as opposed to that found in ponds or wells. But the Samaritan woman did not know this; growing ever more amazed by this pilgrim, she asks innocently: Sir, Thou hast nothing to draw with, and the well is deep: from whence then hast Thou that living water? Art Thou greater than our father Jacob, which gave us the well, and drank thereof himself, and his children, and his cattle?

Our father Jacob… The Gospel according to John, I remind you, is even less a report from the scene of events than the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke: it is the greatest theological poem ever created, one in which, as in any formally perfect poem, there is not a single chance word.

Thus, if John mentions that it was the sixth hour of the day, he is not simply establishing the time at which the Samaritan woman came to the well with her water-container; he is also invoking another event that took place at this very same time: the darkness from the sixth to ninth hours, when the Savior died on the Cross.

This translates the conversation at the well into the context of the lifting up of the Son of Man, as John calls the crucifixion, seeing in it the loftiest manifestation of God’s glory, the absolute and inscrutable manifestation of God’s “mad” love (as Maximus the Confessor put it). We see the same love here, at Jacob’s Well, that we see on every page of the fourth Gospel: a love that discloses itself gradually, step by step, leading up to the Cross. Here there is the same degree of connection between earth and heaven as with the ladder on which the angels ascended and descended, about which Jacob dreamed when fleeing from his brother Esau.

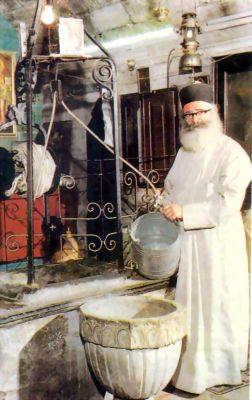

One cannot but recall that Jacob, upon awakening, called the place where he had seen his wondrous dream dreadful, seeing in it not just the place he had camped, but the house of God, which is what he named it by setting down a sacred stone. This very Jacob’s Well, which exists to this day, has become a holy place for Christians: there is an Orthodox church there now, inside of which is the well; in the illustrated guidebook Jerusalem and the Holy Land, released in Israel in 1997, we see a photograph of it with a Greek monk who was later to become the victim of assassins.

One cannot but recall that Jacob, upon awakening, called the place where he had seen his wondrous dream dreadful, seeing in it not just the place he had camped, but the house of God, which is what he named it by setting down a sacred stone. This very Jacob’s Well, which exists to this day, has become a holy place for Christians: there is an Orthodox church there now, inside of which is the well; in the illustrated guidebook Jerusalem and the Holy Land, released in Israel in 1997, we see a photograph of it with a Greek monk who was later to become the victim of assassins.

John creates a context rich in Old and New Testament associations; one that, when overlooked, creates the risk of leaving us with an entirely superficial understanding of what the Evangelist is trying to tell us. The scene at the well, as depicted in realistic paintings (or, more accurately, paintings with pretentions to realism) and in the illustrations in children’s Bibles, is devoid of the parallels important to John, ones that are normally bypassed by both readers and preachers.

By sliding over the surface, one notices neither the sixth hour – when, according to John, the Crucifixion took place – nor the behind-the-scenes story of Jacob, one that in turn connects more and more units of association. Here is the heavenly ladder, employed by Orthodox liturgical rubrics for feasts of the Theotokos; here is the well on the field, and the shepherds at the well with whom Jacob speaks; here is the girl with her father’s sheep; here Jacob went near, and rolled the stone from the well’s mouth, and watered the flock of Laban his mother’s brother. And Jacob kissed Rachel, and lifted up his voice, and wept. And Jacob told Rachel that he was her father’s brother, and that he was Rebekah’s son: and she ran and told her father.

Here is the stone that was rolled away from the well’s mouth, and there is the stone that was rolled away from the tomb, from which, instead of stench, gushes forth the invisible light of everlasting life and the very living water, that is, the Spirit; here is Jacob and there is Jesus; here is Rachel and there is she who speaks with Jesus and runs to her town to tell of Him, just as Rachel runs to her father Laban to tell of Jacob.

Let us return to Sychar. For the Samaritan woman, who asks if Jesus is really greater than Jacob, the answer is clear. It is clear to us, too, but in precisely the opposite way. Jesus answers: yes, He is greater; but He does not answer directly, instead appearing once again to speak about water: Whosoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again: But whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life.

The water given by Jacob, the water of the Old Testament, is not capable of quenching thirst once and for all, like the water in the well or any other water other than that which is given by Jesus. But the Samaritan woman understands water simply as the water that quenches physical thirst, and as no other – which would always be good to have on hand. If this strange pilgrim can in some miraculous way provide such water, then so be it. Sir! – she is most likely addressing Him playfully, not taking His words at face value – give me this water, that I thirst not, neither come hither to draw.

In the Gospel according to John, Jesus and those whom he addresses always speak different languages: He speaks about the heavenly, and they reply about the earthly. However, He never switches to their language; He only sometimes expresses surprise: Art thou a master of Israel, and knowest not these things? Or: Have I been so long with you, and yet hast thou not known Me, Philip? But an analogous question to the Samaritan woman could not have arisen: she, being who she is – neither having graduated from a theological institute nor, most likely, even knowing how to read – could not know or understand. He takes the conversation in another direction, as if recalling the point in the moral code in which the Jews do not differ from the Samaritans: Jesus saith unto her, Go, call thy husband, and come hither. The woman answered and said, I have no husband. Jesus said unto her, Thou hast well said, I have no husband: For thou hast had five husbands; and he whom thou now hast is not thy husband: in that saidst thou truly.

In our times, having five lovers, one replacing the other, is nothing unusual; but having five husbands – that is already a bit stranger. But in the times of Jesus, with their patriarchal and familial structure and strictly regulated life, fairly rigid rules were prescribed; in those times, when there could be no question of independence for women, the situation in which the Samaritan woman found herself was appalling, making her a social outcast.

It is unclear why she had not yet been stoned to death. Perhaps she had been stoned, but not fatally? We know nothing about her life, except that she had had five husbands (or lovers?) and that now she was living with someone to whom she was not a wife, and most likely never would be – which says a lot.

She was an outcast and a pariah, followed by the hateful gaze of women and the lustful gaze of men. This state of affairs will never change within her backwater home. She is like a leper or an accursed woman; the whole town knows that she is a wanton woman, and treats her accordingly. This is the last thing she wants to talk about; having paid tribute to her clairvoyant Interlocutor, she returns to the beginning of their conversation: to inter-confessional relations, as we would call it today. The woman says to Him: Sir, I perceive that Thou art a prophet. Our fathers worshipped in this mountain; and ye say, that in Jerusalem is the place where men ought to worship.

With a prophet, one is supposed to talk about the spiritual. She, however, understands little about this, this is beyond her; she is a woman, and women were supposed to remain silent or ask their husbands, but she neither has, nor will have, a husband. Mount Sion or Mount Gerizim: some say one, others say another. Who is right and who is wrong? Is anybody right? Her manner of living placed her both outside society and outside religion: she is a sinner and will remain such until the end of her days; that is, she is the sort that is abhorred not only by people, but also by God, Whose commandments she does not follow – alas! But what if in fact no one knows the truth, and therefore no one has the right to judge her? She cannot imagine how close she is to the correct answers to all these bewildering questions. In fact, neither Sion nor Gerizim; in fact, no one knows; and, in fact, no one has the right to judge, for that right belongs only to God; and God, writes John, hath committed all judgment unto the Son… and this is the judgment, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil.

Jesus, answering her, begins by clarifying her confused ideas. First, your fathers themselves did not know what they were saying; second, Jerusalem and its Temple are by no means the only place for worship; such a place is not in any way connected to sacred geography – it is in the heart. Believe Me, Jesus says, the hour cometh, when ye shall neither in this mountain, nor yet in Jerusalem, worship the Father. Ye worship ye know not what: we know what we worship: for salvation is of the Jews. The woman is not going to engage in a theological debate: if it is of the Jews, then so be it. For her, however, this is not yet a fact; no one will know anything until the coming of the Messiah, which both the Jews and the Samaritans await. She will believe only the Messiah – if, of course, she lives to see Him; He is her only hope. I know, she says, that the Messiah cometh, Which is called Christ: when He is come, He will tell us all things.

When someone says something like this, he does not normally look at his interlocutor, but at some point located beyond space and time. The Samaritan woman is looking somewhere beyond the verdant fields and vineyards when she hears: I that speak unto thee am He.

So concludes the conversation at Jacob’s Well; and with it, too, concludes my account.

Translated from the Russian.