Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov, the art collector and founder of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, was born 180 years ago today. Together with his brother Sergei Mikhailovich, he collected paintings by Russian artists for over a quarter century, creating the most extensive private art gallery in Russia, which he then offered as a gift, along with the building housing it, to the city of Moscow. To mark his birthday, we offer a brief biographical sketch of Pavel Tretyakov followed by excerpts from an interview with Archpriest Nikolai Sokolov, rector of the Church of St. Nicholas at Tolmachy, which is part of the Tretyakov Gallery and home to the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God.

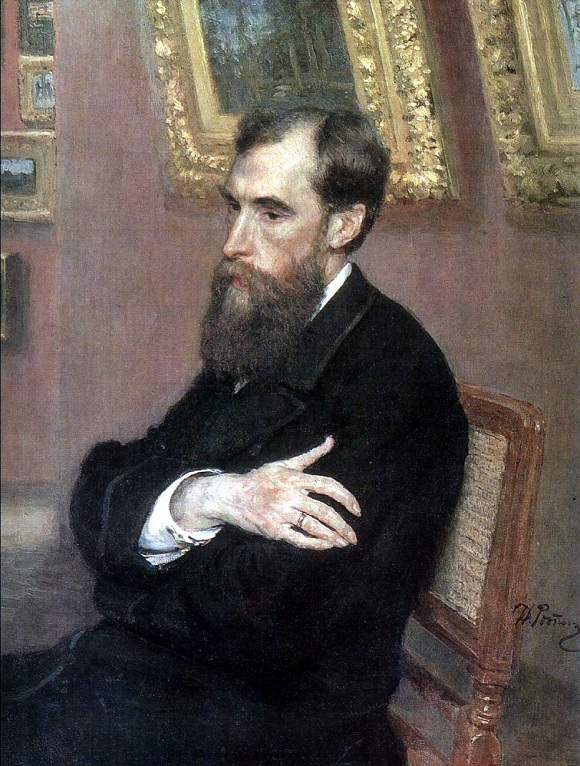

Portrait of Pavel Tretyakov by Ilya Repin (1883)

Pavel Tretyakov was the son of a merchant of the second guild. He received a good education at home and worked with his father, showing a great capacity for work and quick-wittedness. Expanding his father’s work, Tretyakov and his brother Sergei constructed a cotton mill that employed about 5,000 workers. Tretyakov’s character combined kind-heartedness and kindness with exactingness, frankness, and business acumen.

Pavel Tretyakov began to collect Russian art in the 1850s with the intention of donating it to the city. It is believed that he acquired his first paintings in 1856: N. G. Shilder’s “The Temptation” (1853) and G. V. Khudyakov’s “Skirmish with Finnish Smugglers” (1853). Later he added paintings by A. K. Savrasov, K. A. Trutovsky, F. A. Bruni, and other masters to the collection. This patron of the arts made a will in 1860 that stated: “For me, as one who truly and fervently loves painting, there can be no greater desire than to lay the foundation of a publically accessible repository of fine arts that would bring benefit and pleasure to many.”

Tretyakov built a wonderful gallery for his collection in 1874, which was opened to the public in 1881; one year later both the collection and the building were transferred to the ownership of the Moscow City Duma. This institution received the name “The Municipal Art Gallery of Pavel and Sergei Mikhailovich Tretyakov,” while Pavel Tretyakov was named lifetime trustee of the gallery and given the title of Honored Citizen of Moscow. He also patronized a school for the deaf and organized a facility for widows and orphans of impoverished artists. When purchasing paintings, Tretyakov offered very reasonable prices, negotiated patiently with artists, and sometimes turned down works he very much wanted to acquire because he judged them to be too expensive. He minded his expenses so that he could collect as many works as possible in order to represent the Russian school of art not only at its best, but also in all its fullness.

Entrance to the State Tretyakov Gallery today

Pavel Tretyakov continued to expand the gallery for the rest of his life, also bequeathing a percentage of his capital for its future growth, laying the foundation for a museum of international importance. In a letter to his daughter he wrote: “My idea from my earliest youth had been to acquire, so that what has been acquired could be returned to society (to the people) in the form of useful institutions of some kind; this thought has stayed with me my entire life.”

Towards the end of his life, Tretyakov was given the title of commerce adviser, became a member of the Moscow branch of the Council of Trade and Manufactures, and also (from 1893) became a full member of the Petersburg Academy of Arts. He died in Moscow on December 4, 1898. The Tretyakov Gallery became the first publically accessible museum in Russia in which Russian painting was presented not as disparate works of art, but as a unified whole. Through his nearly half century of art collecting and support of the most talented and brilliant artists, Tretyakov had a tremendous influence on the formation and flourishing of Russian artistic culture in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Translated from the Russian

Interview with Archpriest Nikolai Sokolov

Fr. Nikolai, in discussions about church-state relations, which have become especially strained in the past year, I unfailingly cite the example of the recent history of the church at Tolmachy. Many crucial decisions in these regards were made twenty years already, although the controversies and sometimes even accusations do not cease.

I will begin with what is most important. Our church is indeed unique. Today it is a functioning, publically accessible church-museum. Twenty years ago I became the first priest in Russia to receive a salary from the state budget for his service – although not as a priest, of course, but as a departmental head of the Tretyakov Gallery.

Church of St. Nicholas at Tolmachy (Moscow)

Our church has a fairly subordinate status: as a state museum, it is subject in religious terms to the Patriarch of Moscow, but in secular terms to the Ministry of Culture. It does not belong to the Church, but is a museum space, a museum hall. Therefore we coordinate every service with museum management, but they never interfere with us.

Following the museum schedule, the church opens at eight in the morning and, since there are few visitors, divine services are conducted which can be attended by anyone who so desires. Although it should be borne in mind that our entrance is through a police post, a metal detector, and an underground passage, so one needs to leave one’s outer clothing in the cloakroom. Exhibit hours begin at noon. The church is still open to all, but one can only enter through the museum with the purchase of a ticket. Candles may not be lit during exhibit hours. In addition, we have special air conditioning and sensors that constantly monitor the microclimate inside the church. There is video surveillance. We are given to days a year for nocturnal vigils: Pascha and Nativity. The parish warden (a museum staff member) agrees on a schedule with the administration. I should note that all church workers are also museum staff.

At the time the decision was made to restore the church it was being used by the Tretyakov Gallery as a depository. Today I would like us to remember those who took part in its revival and how it all began.

A fate typical of the Soviet era befell our church. The Bolsheviks robbed our church on April 6, 1922, when they seized 157 kilograms of gold and silver articles. On June 24, 1929, the church was transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery as storage for paintings. In the 1930 the bell-tower was ruined: a part of the bells was destroyed and other parts were sold abroad to the USA. Once I was blessing someone’s dacha and its owner boasted that the steps leading to the house were made of fragments of the exterior of a Moscow church located in the immediate vicinity of the Tretyakov Gallery. Only several years later, when I was assigned to the church at Tolmachy, did I understand which church he was talking about. The church’s last rector, Archpriest Ilya Chetverukhin, died in the Gulag in the village of Krasnaya Vishera near Perm.

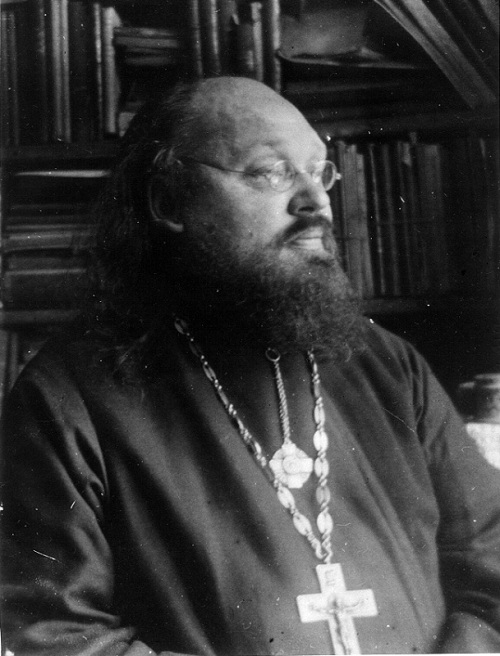

Hieromartyr Ilya Chetverukhin (+December 5/18, 1932)

I am guessing that this will surprise you, but the decision to restore the St. Nicholas Church was made in 1983. Of course, no one was talking about handing it over to the Church; they were planning to restore the church building as an architectural monument (it is over 300 years old) and making it into a concert hall, as was customary in those days. One of the first people who understood the necessity of returning the church to its original use was Yuri Konstantinovich Korolev [1929-1992], who was then the museum director. He felt that the church should become an integral part of the gallery, not as a storeroom or concert hall, but as a place where works of ancient Russian art could be kept – namely icons.

In 1990 Orthodox staff members of the gallery decided to revive the Tolmachy church by forming a church community. His Holiness, Patriarch Alexy II, blessed this undertaking. In 1992 the church’s charter [ustav] was approved, defining its status as a house church of the Tretyakov Gallery.

The charter prescribes that the members of the “twenty,” the parish’s initiative group, could be made up only of staff members of the gallery, along with several parishioners who remembered the church from before its closure. Also included were the children and grandchildren of Fr. Ilya Chetverukhin. I was named rector of the returned church in November 1992. On December 25, 1992, a separate agreement between the museum and the Moscow Patriarchate was signed as a supplement to the charter. On April 23, 1993, the Russian President’s directive “On the transfer to religious organizations of places of worship and other property” came out.

At first, serving was impossible: the church was ruined, there were gaping holes, and there were no windows, doors, or anything else. Seven years had passed from the time the gallery had left the church until it was handed over to us, and it had been left unclaimed and abandoned. Serious repair work began a year after my appointment, lines of communication were laid, and staying in the church became impossible. I had a small room in the gallery.

Reviving this church was difficult; its period of revival lasted for ten years. Relations with the museum staff were not so easy, although sharp conflicts were avoided, by God’s mercy. Of course, problems arise – but it seems that we are able to resolve them all positively, without nervous strain or the involvement of outside forces. Everybody understands that this does not belong to us, that it is not we who are in charge, but rather the Lord Himself.

The Church of St. Nicholas at Tolmachy is once again gradually turning from a museum space into a church. On December 18, 1992, (this day has become our anniversary), on the eve of the feast of St. Nicholas, the first moleben [supplicatory service] and panikhida [memorial service] following the return of the church were served on the commemoration day of its last rector, Hieromartyr Ilya Chetverukhin. As I recall, there were nineteen degrees of frost; everyone was wearing winter hats.

The first Divine Liturgy was served in 1994. On September 8, 1996, after the completion of all construction and restoration work on the five domes and the bell-tower, the church’s main alter was consecrated by Patriarch Alexy II. The divine service was celebrated in the presence of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God.

Speaking of icons, we must mention one of the greatest of Orthodox sacred objects: the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God. It was for the sake of this icon – to give the faithful the opportunity to pray before it – that our church was returned. But, as is well known, this was no simple matter. Were the concerns of the opponents of transferring the icon to the church, even as part of the museum, not justified?

On September 7, 1996, the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God was first placed in the church in a special icon case [kiot]. On September 8, on the feast day of the icon, Patriarch Alexy II performed the consecration of the church. Henceforth, September 8, the feast day of the Vladimir Icon, has been our main parish feast day. Before this time, for several years I served molebens before the icon right in the hall of ancient Russian art. The gallery was not closed; tours passed by.

Archpriest Nikolai Sokolov praying before the Vladimir Icon

It is understandable that housing such an icon required a special technical solution in order to ensure its complete safety. Specialists from a Moscow base metal factory offered to make a special capsule that would not only ensure its safety, but also maintain the temperature from 18 to 20 degrees Celsius, with 55% humidity. This is a unique engineering solution that had not previously existed in Russia, and also required money. The armored glass alone cost about 10,000 marks, which in the mid-1990s was no easy matter. Moreover, technical solutions from the experience of mausoleums and combat aircrafts were used. As a result, the capsule ensures the icon’s safety in any situation, whether in water or fire; it can sustain a grenade blast and a round from a Kalashnikov; it even cuts off ultraviolet and infrared radiation.

The process of manufacturing and debugging the whole system took several years. At first the icon was brought in, put in place, and checked for its climatic condition. Then it was removed and checked for safety. Even now, staff members regularly open the glass and check the icon’s condition. Today the faithful can venerate the Vladimir Icon through the glass; the icon case is opened only for His Holiness the Patriarch.

After a series of experiments and several variants of capsules, a final decision was made in 1999, and on December 15, the director of the Tretyakov Gallery issued order No. 958, prescribing that the sacred object be placed in the icon case. Russia’s foremost sacred object has been kept in the St. Nicholas Church since January 2000. This has been done in large part thanks to the labors of the gallery’s director, Valentin Alekseevich Rodionov. He was able to establish the best possible relationship with the Church, which today allows for the gallery’s thousands of visitors to see and do justice to these great sacred objects, and for the faithful to pray before them.

Interview conducted by Evgeny Strelchik

Translated from the Russian

You might also like:

Rublev’s Trinity Transferred to Church for Pentecost

The Vladimir Icon and God’s Role in History

The Intercession of St. Nicholas in Our Days