I pray for success and happiness…

Several faithful entered the gates of the Donskoi Monastery. They got to Patriarch Tikhon’s waiting room, then waited for several hours – there were many people and His Holiness was well loved. Then they entered a small office and, taking his blessing, they asked St. Tikhon their single question: “Bless us to die for Christ and the Church.” Patriarch Tikhon remained silent, and then pronounced the following words with a sad smile: “Dying is easy, very easy. It’s much harder to live for Christ and the Church.”

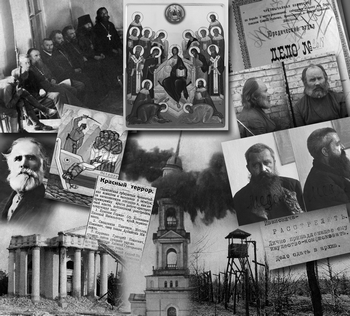

I often think of St. Tikhon’s phrase when it comes to talking about the New Martyrs. This Sunday we will be remembering the Synaxis of the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church, and this is perhaps the only form of commemoration in church that I can understand.

I can’t imagine a moleben with akathist, for instance, to the Martyr Tatiana Grimblit. I have nothing to ask of her: in the years of persecution she sent parcels and letters to the confessors, and visited them. For which she was arrested five times and finally shot on September 23, 1937 at Butovo. The only thing that I could theoretically ask the New Martyrs for is my well-being, that the Church not be persecuted, and that I could die a happy old man in my own bed, surrounded by children and grandchildren.

I hesitate to appeal to the Martyr Tatiana with such a request, and therefore I pray to other saints: holy hierarchs and monks. From them I might ask for a successful trip, help in writing articles, the health of my neighbors, and the strength to do my job well.

I pray for success and happiness, and therefore I do not need the New Martyrs. When I read their lives I experience something, but at any moment I can close the book or turn off the film.

As a teenager, it’s nice to watch the cartoon “Superbook,” in which a boy and girl are always wanting to save Christ from the Passion, but too late. In each series they don’t manage, and the evangelical story goes on.

Such logic is clear and close to home for me. The teenager and neophyte wants to perform a miracle: to fly into Jerusalem with a gun and endless life, shoot down the crowd and the Roman soldiers, save Christ, and… ruin His entire mission.

I am not alone in this desire: the Apostle Peter in Gethsemane would have solved all the problems with the help of a knife. It’s normal to fear suffering and death, and to save the good guy from them.

I understand the Christians who visited the ancient martyrs in prison, but can’t judge those who bribed the Roman officials to put their names on the list of those who’d offered sacrifices for the Emperor’s health.

From my small experience, I know how to soften the angles, to negotiate, to compromise, not to look for trouble.

I can easily answer the question: “Why did a saint enter a monastery, give beautiful sermons, or build churches?” They were making the world a better place, leaving a good memory of themselves behind, moderating morals. They could have disciples.

In contrast to them, the martyr is always alone: he doesn’t pass on his experience to his disciples, nor gather a group of the like-minded. The Church is well aware of this and never advises Christians to seek martyrdom.

As a believer, I rarely think about the New Martyrs.

But I am also a researcher: I have for many years been studying the lives of saints and the history of the Church: I read monographs and lives, I study documents, and I see how dangerous it is to regard the struggle of the New Martyrs as a battle against the Soviet power or, on the contrary, to regard them as apologists for the regime. They gave their lives for Christ, not for some form of ecclesial or state structure.

Witnessing to Christ was the main theme of any martyrdom. Otherwise, the Church can turn into a kind of party and begin to divide Christians into their own or not their own depending on secondary characteristics. This is very evident from Old Believer hagiography. A few years ago I read a patericon written by a contemporary author. It respected all the formal elements of the hagiographical genre: the strugglers prayed and fasted, suffered and healed – but all this was cold and dead, in contrast to the “Life of Avvakum.”

With every page of the narrative, the saints seemed less and less like Christians. Closing the book, I understood the reason: the entire lives of these strugglers weren’t dedicated to the imitation of Christ, but to a battle with the “Nikonians.” Their struggles were so tightly bound up with this battle and the desire to prove the correctness of their own Church that they ceased to be Christians, finally becoming only preachers of their own ritual.

I become a believer anew and recall the fate of Metropolitan Nicholas (Yarushevich), who was a very complex man and who will unlikely be canonized in my lifetime, but in 1943, after a meeting of Stalin with the Orthodox hierarchy, he in fact became a martyr in life. “They said God knows what about him,” related Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, “but he told me that Vladyka Sergius asked him to become the intermediary between him and Stalin. He refused: ‘I can’t…’ ‘But you’re the only one who can do this, you must.’ He told me: ‘I lay before the icon for three days and cried out: Save me, Lord! Deliver me!…’ After three days, he got up and gave his consent. After this, not a single person crossed his threshold, because the faithful stopped believing that he was one of their own, while the Communists also knew that he was not one of theirs. He was only encountered at services. Not one person offered him his hand, in the broad sense of the word. What a life! This is just as much a martyrdom as getting shot.”

Translated from the Russian.