Have you ever wondered why the faces of saints on some icons are so stern and threatening that they are frightening to look at? Why was St Christopher portrayed with a dog’s head which made him look more like the Egyptian god Anubis than a Christian saint? Is it right to portray God the Father as a gray-haired old man? Can we consider Vrubel’s and Vasnetsov’s images of angels and saints to be icons?

Although icons and the Church are virtually as old as one another and icons have been painted for centuries according to strict rules, yet in this field too there are errors, disagreements and arguments. What should our attitude be? Ekaterina Dmitrievna Sheko, Head of the Department of Iconography at St Tikhon’s Orthodox University, explains.

Anubis or St Christopher?

St Christopher. Icon of the first half of the 17th century.

– The portrayal of St Christopher with a dog’s head was prohibited by Synodal order in 1722. But popularly he continued to be portrayed in this way even after the prohibition, in order to make him stand out him from all the other saints. However, in Serbia or in Western Europe, for example, St Christopher is portrayed in a different way, carrying a boy across a river on his shoulders. This is a tradition.

– What is the difference between a tradition of painting and a rule?

– Rules for Church services clearly define certain rules and acts, but it is difficult to do this in the field of icon painting, since – generally speaking – a rule here is above all a tradition. Nowhere does it say that you have to paint this way and no other way. But the tradition itself was formed by generations of believers, many of whom ascended to higher levels of the knowledge of God than we do today through their ascetic life and prayer. This is why when the artist and icon-painter studies traditional iconographic techniques, he draws closer to the knowledge of the truth.

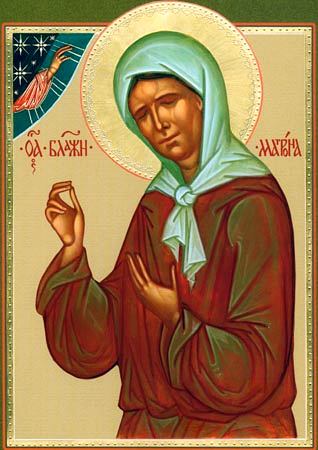

Is Blessed Matrona not blind then?

– So it turns out that every painter adds some details at his or her discretion. For example, we are used to seeing icons of Blessed Matrona with her eyes closed, and the most popular icon (the Sofrino one) depicts her blind. Yet there are some icons where she can see. After all, there will be no disabilities after the Resurrection…Where is the truth here?

– Opinions vary on this point. My spiritual father believes that it is incorrect to depict her blind on the icon and I agree with him. Since Blessed Matrona has been canonized, she cannot be blind, because in heaven there is nothing physical, including infirmities, disabilities or wounds.

– Then, please explain why it is normal to depict wounds on the hands and feet of the Savior?

– Then, please explain why it is normal to depict wounds on the hands and feet of the Savior?

– We know from the Gospel that Christ rose from the dead and bodily ascended into heaven and that there were nail marks on His hands and feet as well as the spear wound on the ribs. And after His Resurrection He showed them to Thomas the Apostle and let him touch them.

– Are there any canons on whether we should portray injuries to the bodies of the saints or not?

– No, there aren’t, that’s just the point. Anyway blindness was not depicted anywhere else. Matronushka’s icon is the exception, though of course there were blind saints in Church history. It is a great pity that there are no Synodal decisions about the iconography of St Matrona which would be binding for the whole Church…

But I think that in the case of this icon it is not even a question of open or closed eyes, but something else. In my opinion, the most popular icon of Blessed Matrona is not only controversial from the standpoint of iconography. The image is very ugly, poorly done, and the face does not have anything in common even with the photo of Matronushka which was taken when she was alive. The photo shows a rather well-rounded face of the saint, a large nose, soft, rounded cheeks and a pleasant look. And here everything is so dried up, she has the thinnest of noses, a huge, frightening mouth, a tense face, the eyes are shut tight and do not express calm. The work is clumsy and ugly. Of course, we can break away from the portrait resemblance, but the icon must express the spiritual aspect of the person and not distort it.

A saint’s face in an icon comes from their tormented face in life.

– Should the painter strive to obtain a perfect similarity between the face in the icon and that in life?

– Some believe that the portrait resemblance is secondary, as it is an element of the fleshly nature of man. For example, Patriarch Tikhon had a very large nose and some icon painters think that there is no need to reflect this in the icon and that his face should be painted in a more generalized manner close to traditional iconography. Such matters are discussed behind the scenes, but the clergy have no common answer, there are no Synodal statements on such issues.

– Do you think it should be done?

– I do. Everything that happens in the Church, especially anything that is connected with prayer, should be discussed in all seriousness at Councils. After all an icon is designated to help us pray, since people turn to God and His saints through icons.

The style of the icons that were painted at the beginning of perestroika was discussed very carefully by both icon painters and clergy. For example, the process of creating icons of Patriarch Tikhon, Ambrose of Optina, Elizaveta Feodorovna was lengthy and thought through very carefully. I remember how it all happened and I think that at that time it was quite right. Firstly, we all prayed about it and secondly, we discussed the artistic aspect as well. Later, after the canonizations of huge numbers of saints, we lost the possibility to study the iconography of each one with such great care.

– Who are the saints whose iconography creates most problems?

– It is complicated to paint the New Martyrs. They are more or less our contemporaries and we know their faces and this forces us to refer to their portraits. But sometimes all we have is a concentration camp photo taken by the NKVD. Once I had to paint a priest from such a photo. He had been shaved, he had been starved, tortured, interrogated, driven to the extreme of physical exhaustion and sentenced to death – it was all written on his face. And it is extremely difficult to make an iconographical image, shot through with light, out of such a tormented face.

Pre-revolutionary photos are wonderful, they are already icons. For example, the faces of Patriarch Tikhon or John of Kronstadt who did so much for the good of the Church are already transfigured in themselves. Also the tradition of photography was still alive at that time – the photographer caught the mood, the state of mind. But of course the NKVD photos are awful…

Or, for instance, the iconography of Archbishop Luke Voino-Yasenetsky is very complicated. As a result of many terrible incidents in his life his face was slightly irregular, he saw poorly in one eye, so his face was somewhat indistinct. So you must have certain talents to create a new icon and not just copy a traditional one.

On ‘Corporate’ Caution.

– Are there many non-canonical icons in the Russian Church at present?

– The number has been growing more and more in recent years, precisely because our bishops are silent. There has been no decision on what must not be done. I believe that an official decision on this would be enough to stop artists falling into extremes.

We have some internal controls, a certain caution – people who are serious about iconography look at each other’s work, seek advice and discuss what each other does. For example, in the West there are no limits at all, everybody does whatever they want. We are more careful, but this is a sort of internal,’corporate’ principle. There are no strict rules.

– And what is the advantage of keeping to rules? Where does it help?

– I think the knowledge of certain iconographical rules and traditions gives you the opportunity within those boundaries to express spiritual truth though pictorial art. We have some common elements which have been worked out down the centuries and verified by many generations. We can use them to show spiritual things and it is unwise to ignore them. Apart from this, it is also a link between different periods, a link with many generations of believers, with righteous Orthodox and ascetics.

A Synodal decision?! So what?…

– We can also feel this link between different periods in the opposite sense. When you enter a 18th or 19th century church, you look up and see the image of ‘the New Testament Trinity’ beneath the dome. And yet the Local Council of Russian Orthodox Church in the 17th century forbade representations of God the Father as a gray-haired old man. Why are such images still in churches?

– This image is the result of Western influence. In the 17th and 18th centuries there was a huge muddle in Russia, the Church was beheaded – during the reign of Peter I the Synod came into being as the State body to govern the Church. The authority of the Orthodox Church was undermined by the authority of the State. Though the Council prohibition had been issued, it was still totally disregarded in the 19th century.

– But surely the decision of a Council was binding?

– It does not seem to have been. Although there was no official permission for such images, we do not have any to the present day either. I suppose that the Church hierarchy is for some reason afraid to limit artistic freedom. I don’t know why. Art experts are given complete control to discuss iconography and the clergy often take a back seat because they consider that they are not competent. Though sometimes we see the other extreme, when priests do as they think fit without any consideration. Unfortunately, no general opinion of the Church has been formulated.

And why Rublev? We can do better!

– Does the Church recognize the paintings of 19th and 20th century artists like Vasnetsov, Vrubel etc. as icons?

– Again, there is no one opinion in the Church. Some recognize these paintings as icons, others do not. No bishop has said anything regarding the images of Vasnetsov, Nesterov or Vrubel, no one has said anything at a conference or at a Council on what is right and what is wrong, on where the limit of what can be permitted is.

– Is it possible in principle to consider that a secular style drawing is an icon?

– Yes, sometimes. But that does not mean that we must aim to have a secular style.

I remember one example, when I was working on the fresco restoration project in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and there was an argument. Many said that there was no need to restore the original secular style of painting, instead something brand new had to be done as a matter of principle – for example, a modern mosaic. At that moment some artist came forward and said: “Of course, it won’t do, we need to do a real fresco …” He was asked: “And what examples do you suggest we take?” And he answered: “Well, for example, Rublev…And why Rublev? It’s possible to do better!” And when he said this, everybody understood that there was no need for better! Since when someone says that he can do better than Rublev, that raises all sorts of doubts.

– But probably no-one will ever paint like Rublev. The icons of the 14-15th centuries are of one style, Renaissance icons are another and modern icons are another again. And you can’t confuse them. Why is that?

– Iconography reflects our surroundings in life, all human events, images and thoughts. In Rublev’s time, when there was no television, no film industry and not such a huge amount of printed images as nowadays, iconography rose to great heights.

There were still fine examples in the 17th century since certain standards were maintained, but you could already find some confusion in iconography, an over-indulgence in the decorative. The depth of content of the icon was lost. And the 18th century is decline because what was done to the Church at that time could not help being reflected in iconography. Many bishops were killed and tortured, any Orthodox tradition and legacy was considered to be retrograde and brutally uprooted. There was fear of doing something which would displease the authorities. This had an impact on everything, it was always at the back of people’s minds.

– And how do you explain the fact that medieval dissymmetry, disproportionately large heads, for example, have disappeared in icons?

– They disappeared because painters know how to give the right proportions to the human body. Disproportion and deformity are not the goal of icon painting.

– But some Cypriot icons still have such disproportion, for example… Have they not learnt anything at all then?

– It depends on the school. The Greeks also strive to keep the old traditions; they do not go in for a secular style. Rublev and Dionysius did not change the proportions because they could not draw in a secular style but because they were men of great gifts and free of blinkered convention. And now it is considered that if a painter has mastered the secular style, it means that he will be good at icon painting. In fact, he will be painting the way the later 16th and 17th century painters did – with correct proportions, correct perspective and a correct reproduction of dimensions. These are two extremes: either an iconographer can do nothing and just “daubs” or else he studies secular painting seriously, at the Surikov Art School in Moscow, for example, and then he tries to break himself into the techniques of icon painting. But that is very difficult.

Why pray in front of the icon, if it does not speak to us?

– Has modern icon painting not become more realistic?

– No, not at all. It depends on the extent to which the practices of the painter who has been trained in secular art influence his icon painting, often unconsciously.

– Is it a mistake when a face on the icon looks too stern and strict? Or should we see something through this sternness?

– That is just a lack of skill.

– Why should we use models? Classic iconography shows that a face in an icon can be beautiful.

– They set us an example and if we manage to get close to it, that would be very good. But if we work in own individualistic way, the chances are that nothing good will come out of it because nowadays we have a very distorted way of life.

– What is happening in icon painting today?

– Nowadays there are a lot of people who are completely ignorant of the classics and simply do not know how to paint. Icon painting has become a very profitable business, so now icons are painted by anyone who feels like it. Even people who have painted two or three icons have already started calling themselves icon painters. Today it is much easier, quicker and more profitable to sell an icon than a landscape. So now any icon sells like hot cakes. You look in the small shops and you can find dreadful-looking icons and they all find a buyer. The market is like a sponge, it is not saturated yet. There are a huge number if errors.

– What, in your view, is the criterion of a good or a bad icon?

– I think the main content of any image – even it is a secular painting – is the state of mind of the person depicted. There are secular style icons which are very spiritual – these are the icons of St Dimitry of Rostov, St Joasaph of Belgorod, the Valaam Icon of the Mother of God. They convey the state of divinisation: dispassion and firmness as well as benevolence and peace. And why pray in front of an icon that does not speak to us? For example, as in Vrubel – there are some frightening, insane looks. The form might be very good, but the main thing is the content.

Translated from Russian by Elena Demidova

Edited by Fr. Andrew Phillips

You might also like: