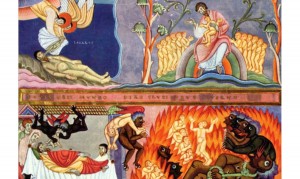

The Lord said, “There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day: and there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores, and desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores. And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the Angels into Abraham’s bosom: the rich man also died, and was buried; and in Hell he lift up his eyes, being in torments, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom. And he cried and said, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame.’ But Abraham said, ‘Son, remember that thou in thy lifetime receivedst thy good things, and likewise Lazarus evil things: but now he is comforted, and thou art tormented. And beside all this, between us and you there is a great gulf fixed: so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence.’ Then he said, ‘I pray thee therefore, Father, that thou wouldest send him to my father’s house: for I have five brethren; that he may testify unto them, lest they also come into this place of torment.’ Abraham saith unto him, ‘They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.’ And he said, ‘Nay, Father Abraham: but if one went unto them from the dead, they will repent.’ And he said unto him, ‘If they hear not Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead’” (Luke 16:19-31).

This parable is one of the most paradoxical. There lived a man who didn’t do anything wrong. He was rich. Is that really a bad thing? As they say, it’s better to be rich and healthy than poor and sick. And then there was Lazarus. He certainly was poor. But what was virtuous about that? Is it a virtue to be sick, starving, and generally to suffer? Hardly.

This parable is one of the most paradoxical. There lived a man who didn’t do anything wrong. He was rich. Is that really a bad thing? As they say, it’s better to be rich and healthy than poor and sick. And then there was Lazarus. He certainly was poor. But what was virtuous about that? Is it a virtue to be sick, starving, and generally to suffer? Hardly.

What’s the deal here? Why after death does the rich man suffer in hellfire, while Lazarus rests in the bosom of the Forefather Abraham? Can it really be simply because everything has to be counterbalanced and compensated, so that after a sumptuous life on earth there comes suffering, but after suffering comes joy? That’d be strange.

But the whole point of a parable is to make us think. So let’s stop for a moment and think about it.

The parable doesn’t simply talk about two people with different fates and unequal shares in the afterlife. Lazarus (and this is important) lay at the rich man’s gates. Consequently, the rich man saw him every day and was well aware of what his needs were – but apparently he wasn’t in any hurry to get involved. (And in fact Lazarus wasn’t some kind of pagan: he was the rich man’s fellow tribesman, an equally right-believing Jew.)

None of this means that the rich man (that’s what we have to call him, since the Gospel doesn’t tell us his name) was wicked and cruel. Perhaps he simply didn’t want to spoil his happy, comfortable life by coming into contact with disease, poverty, and death.

Let’s recall the Russian classic [Tolstoy’s War and Peace]: “Natasha too, with her quick instinct, had instantly noticed her brother’s condition. But, though she noticed it, she was herself in such high spirits at that moment, so far from sorrow, sadness, or self-reproach, that she purposely deceived herself as young people often do. ‘No, I am too happy now to spoil my enjoyment by sympathy with anyone’s sorrows,’ she felt, and she said to herself: ‘No, I must be mistaken, he must be feeling happy, just as I am.’”

Humanly speaking, this is quite understandable. But God’s judgment is something else entirely.

And what about Lazarus? He lay there, poor, sick, festering with wounds, surrounded by dogs and, as the Gospel says, wanting to be fed with the crumbs that fell from the rich man’s table. Who knows, maybe this happened sometimes.

But is suffering of value in and of itself in God’s eyes? Hardly. Does it really please God to regard our suffering? And can suffering in and of itself really redeem sins?

No, something else is needed here. Namely, the readiness to accept God’s will without murmuring, complaints, or curses. If we patiently endure – even if not torment or suffering, but just some kind of inconvenience – with the faith that the Lord is sending us a test; and if we accept what has been sent with gratitude – then we can hope that our patience will be imputed unto us for righteousness.

This was obviously the case with Lazarus. He lay at the rich man’s gates, possibly for many years. And when he died, angels came for him. They probably came for a reason. But about the rich man it just says that he “was buried.”

Let’s repeat it one more time: the rich man was not wicked and cruel. After all, even in Hades, when it would seem that his own suffering would’ve overshadowed everything else, he remembers his brothers, and worries about them. But, as they say, being a good person isn’t a profession.

Christ expects from us not abstract beauty of soul, but specific deeds that would show our faith and our love. He Himself didn’t distain joining with matter, being born in a stable, and dining with harlots. He expects the same thing of us: not closing ourselves off, not cordoning ourselves off from “other people’s problems,” but rather actively participating in the lives of those who stand in need of us.

So why did the Lord condemn the rich man? Because he had done something bad? No, because he didn’t do good.

This parable is extremely important for us. We Christians who go to church and regularly have Confession and Communion are, on the whole, good people: we don’t kill, we steal almost nothing, and we don’t get in each other’s way.

But the Lord didn’t say: “Don’t get in each other’s way.” He said: “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” And our love needs to be active and effective.

So, if one fine day (and may God grant that it be in this life), we realize that the Lord is displeased with us, let’s not ask ourselves: “But what did I do?!” Let’s ask ourselves: “What have I not done, from what I could and should have done?” Let us ask, and then answer with deeds.

Translated from the Russian.