After an incredible, almost unbelievable life, one man tells THEO PANAYIDES how his search for love was finally successful

Klaus Kenneth is God’s gift to newspapers. His life, as he tells it, has been so full of incident and adventure that the only problem for a journalist is how to fit it all in. He was a gang leader at 12, a terrorist at 22 and a junkie at 25. He’s been a Buddhist monk, a Hindu mystic and an occultist in Central America. He’s known Andreas Baader (of Baader-Meinhof fame) and Mother Teresa. The biography on his website (www.klauskenneth.com) offers more talking-points than could ever be encompassed in a single interview. Here, for instance, is the entry for the year 1980: “Fribourg, Switzerland; Professor in Gruyeres (private school); demon attacks; destruction of all relationships; isolation accentuated; refuge in alcohol; ecstasy through dance; first letters about Jesus from Ursula.” You don’t write a Profile about Klaus; the Profile writes itself.

Klaus Kenneth is also God’s gift to churches – especially the Orthodox Church, which is where he turned after decades of spiritual wandering, a meeting with Father Sophrony of Essex (a man whom he describes as “Love incarnate”) leading to a full Orthodox baptism in 1986. Klaus was in Cyprus for a few days, speaking – mainly in churches – about his turbulent life and recently-published autobiography Born to Hate, Reborn to Love (the better German title translates as ‘Two Million Kilometres of Searching’). We speak at the Church of Apostolos Andreas in Aglandjia, just before his lecture – and, just as I turn on my tape recorder and start to ask the first question, the church bells start to peal loudly, making him smile. Back in Mexico, muses Klaus, when he was summoning spirits, such a coincidence would be seen as “a sign from the spiritual world”.What kind of sign? A good sign?

Probably, he shrugs. After all, the bells are a way of summoning believers to the church, and “the church is life-giving. But the church is also death-giving sometimes, when the priests are not good.”

Has he had that kind of bad experience?

“Well,” he shrugs again, “I was violated by a homosexual priest for seven years every night, so…”

That’s the thing about talking with Klaus: he’s ventured down so many extreme paths in his life that one often struggles to keep up. What might be a shocking revelation for most people is, for him, just a throwaway. “Have you ever driven 1,500 kilometres, without any sleep, in the desert?” he asks at one point. (No, Klaus, I can’t say I ever have.) “I’ve been clinically dead for six hours,” he mentions later, almost in passing. What? Really? And he’s seen a brilliant light, and all the other things we hear about? “Life after death? Of course, I describe that in my book.” His life is so crowded that some things don’t even rate a mention. “I’ve survived so many times,” he says at one point. “The war in Israel, and I was going between the tanks, and…” he flaps a hand dismissively, not wishing to bore me with trifles: “These are other stories.”

That’s the thing about talking with Klaus: he’s ventured down so many extreme paths in his life that one often struggles to keep up. What might be a shocking revelation for most people is, for him, just a throwaway. “Have you ever driven 1,500 kilometres, without any sleep, in the desert?” he asks at one point. (No, Klaus, I can’t say I ever have.) “I’ve been clinically dead for six hours,” he mentions later, almost in passing. What? Really? And he’s seen a brilliant light, and all the other things we hear about? “Life after death? Of course, I describe that in my book.” His life is so crowded that some things don’t even rate a mention. “I’ve survived so many times,” he says at one point. “The war in Israel, and I was going between the tanks, and…” he flaps a hand dismissively, not wishing to bore me with trifles: “These are other stories.”

He was born in 1945, just after the fall of Berlin (his birthday is actually today, May 15), and grew up in Germany, though he’s currently based in French Switzerland. His mother “gave me away” to the evil priest when he was 15, by which time he’d become unmanageable. “I was revolting against her, because my mother didn’t have love,” he explains. “I had a gang – I mean a robber gang – and we were breaking shops and stuff like that, and made gang wars between each other. I was un-educatable”. His father left the family when Klaus was a baby, leaving Mum to take care of him and his two brothers – but his mother, he recalls, “just could not stand me, and I could not stand her… I never had a family. I don’t know what it is to have a family, even nowadays.”

One brother left to join his father; the other stuck it out till adulthood, then fled to America and started a new life. Klaus lost touch with both of them, though he tracked down his dad in Stuttgart years later and was reunited with his brothers. “I forgave them later,” he asserts. “In the name of Christ it’s possible – otherwise I would kill them”. And what about his mother? Did he forgive her too? “I forgave her, but she was so possessed with demons. She was all the time full of demons.”

Real demons, or metaphorical?

“No, no, real demons. She called them, and she was influenced by them. And she was like crazy sometimes, it was terrible living with her.” Violent too? He nods: “She could beat me half to death sometimes. With a metal stick.”

All this rage came out in his gang of teenage hoodlums: they threw rocks, robbed people, even burned a man’s house down. “I was suffering,” he says now. “I just knew ‘do them bad’, because they did bad to me”. This was also when Klaus first realised he had power over people. “I found very quickly that I’m a leader… I just knew when I spoke to people, I was somehow convincing, and they followed me. So [I’d say] ‘Beat this guy up’ and they beat the guy up, you know?” In his early 20s, having finally escaped the clutches of the priest, he was studying Languages at the University of Tubingen – but was soon seduced by Andreas Baader, who was recruiting students for his “violent movement” aimed at the wholesale destruction of German society. Klaus, full of hatred, was ripe for the picking: “Police was enemy. Teachers were enemy. Priests were enemy. My mother was enemy. Everybody was enemy”. He pauses: “Because there was no love”.

It wasn’t just violence, he points out; there was idealism there too. “We really believed that we could change the world” – forgetting, he adds, that you first have to change yourself. “We thought we could do it by drugs and making love, free sex. [But] we ended up in passion instead of in freedom.” In any case, he soon discovered that “violence is not my way” – and also discovered that drugs only made things worse, amplifying his feelings of alienation instead of resolving them. At one point, he recalls, when he looked around at people “all their faces became skulls… I projected Death in everybody”. In any case, by the early 70s he’d “found a better drug: it was Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Transcendental meditation.”

Thus began his years of spiritual wandering. “I was an earnest seeker,” he tells me, though he must’ve seemed like a spiritual tourist, this half-crazy German plunging into one Eastern religion after another. Islam never appealed to him: “This is law, law and law. It didn’t give me love” – but he spent seven years exploring Hinduism, visiting all the great gurus in India (“I found very quickly they were often fakes,” he scoffs, “full of pride”), then three more years in Tibet as a Buddhist.

This is also where Klaus’ account of his life veers into claims that some will find incredible, like his description of the powers he wielded during those years – an extension of his old power as a gang leader, honed and perfected by years of meditation. “I could see people’s thoughts, what people think about” – not the precise thoughts but the “direction”, which he then manipulated. “I could make myself invisible. I started to hear voices from the beyond. I was a medium”. He had frequent out-of-body experiences. Dead gurus spoke to him, giving audible messages in English. “I had power. I was in New York and six gangsters wanted to kill me. And when I looked in their eyes, I could bind them. I had the power. When I had eye contact, I could just paralyse them”. Like hypnosis? It wasn’t hypnosis, he demurs, it was the power of the spirits. “I looked at people in the eyes, and when they were somehow not sure of themselves, I just got them somehow, I had power over them. Especially, in my case, for girls, of course – because you want to make sex. It’s not love, but it’s a substitute. Better to have substitute than to kill yourself.”

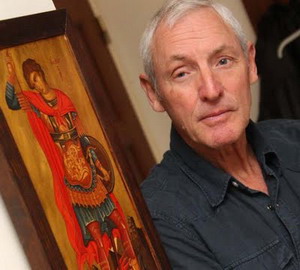

It’s not entirely implausible. Even now, at 66, Klaus cuts a striking figure: thin-faced, dressed in black, with close-cropped silver hair and narrow, unblinking eyes. There’s something compelling in those eyes, even if it’s just a hardness and lack of humour. Didn’t he ever have fun in those decades of wandering? Didn’t he ever just relax, maybe crack a joke? But he shakes his head: “No, it was lonely, it was very lonely. I was lonely all the time.”

Oddly enough, the person who impressed him most in India was a Christian – a religion he’d definitively abandoned after his years of abuse. That was Mother Teresa, whom he met in Calcutta: “She was my first mother,” he says poignantly. “The first person who had love for me, unlimited love. I thought such a person can not be a Christian – I even tried to convert her to Hinduism!”

Mother Teresa was the first step on the second part of Klaus’ journey – the journey back to Christianity, which of course is why churches invite him to share his experiences. It’s a journey that’s impossible to describe in detail without writing a book about it (as Klaus did), but it does include two crucial events which demand to be mentioned. The first was a miraculous escape in South America, when Klaus was abducted by Colombian rebels – who, realising they could get no ransom for him, decided to shoot him. Lying naked in a muddy ditch with seven rifles pointed at him, Klaus cried: “God, if You exist, save me now!” – and, right on cue, another rebel group emerged from the jungle, prompting a shoot-out with the first group and allowing him to flee in the confusion.

That was in 1981, just a few months before the second great miracle – when Jesus actually spoke to him, in a church in Lausanne. “Jesus,” asked despondent Klaus out loud, “do you want me to come to you or not?” – and Jesus, “as clear as you hear me now,” speaking French “in a sweet, indescribable voice”, replied: “Yes, come. I have forgiven you everything”. “And I was never touched so deeply,” he says quietly, “in my heart, in my being, as in that moment.”

There’s more, of course – much more. That communion with Our Lord was preceded by not one but two exorcisms (the priest in Lausanne insisted) and followed by what he calls a “counter-attack of Satan”. And I haven’t even mentioned all the other things, the miracle in the Syrian desert circa 1971, the George McGovern story, the levitation… I look at Klaus, unsure what to say. You do realise, I ask finally, that when I write this stuff in the paper, people will read it and say –

“Crazy man,” he agrees.

They won’t believe you.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

So what do you say to those people?

“Well, you are right not to believe it,” he replies, “because it sounds incredible. But I can not lie in the name of Christ – because I would condemn myself to Hell. And I lived in Hell. I don’t want to go back there.”

Maybe that’s the crux of it, when it comes to Klaus Kenneth. Mystics will say he found God, psychologists will say he found closure, but the story’s much the same whichever way you want to tell it: the story of a man who was raised without love, coldly and abusively – who “lived in Hell,” as he puts it – wandered for years trying to find inner peace, and finally found it.

After an incredible, almost unbelievable life, one man tells THEO PANAYIDES how his search for love was finally successful

Klaus Kenneth is God’s gift to newspapers. His life, as he tells it, has been so full of incident and adventure that the only problem for a journalist is how to fit it all in. He was a gang leader at 12, a terrorist at 22 and a junkie at 25. He’s been a Buddhist monk, a Hindu mystic and an occultist in Central America. He’s known Andreas Baader (of Baader-Meinhof fame) and Mother Teresa. The biography on his website (www.klauskenneth.com) offers more talking-points than could ever be encompassed in a single interview. Here, for instance, is the entry for the year 1980: “Fribourg, Switzerland; Professor in Gruyeres (private school); demon attacks; destruction of all relationships; isolation accentuated; refuge in alcohol; ecstasy through dance; first letters about Jesus from Ursula.” You don’t write a Profile about Klaus; the Profile writes itself.

Klaus Kenneth is also God’s gift to churches – especially the Orthodox Church, which is where he turned after decades of spiritual wandering, a meeting with Father Sophrony of Essex (a man whom he describes as “Love incarnate”) leading to a full Orthodox baptism in 1986. Klaus was in Cyprus for a few days, speaking – mainly in churches – about his turbulent life and recently-published autobiography Born to Hate, Reborn to Love (the better German title translates as ‘Two Million Kilometres of Searching’). We speak at the Church of Apostolos Andreas in Aglandjia, just before his lecture – and, just as I turn on my tape recorder and start to ask the first question, the church bells start to peal loudly, making him smile. Back in Mexico, muses Klaus, when he was summoning spirits, such a coincidence would be seen as “a sign from the spiritual world”.What kind of sign? A good sign?

Probably, he shrugs. After all, the bells are a way of summoning believers to the church, and “the church is life-giving. But the church is also death-giving sometimes, when the priests are not good.”

Has he had that kind of bad experience?

“Well,” he shrugs again, “I was violated by a homosexual priest for seven years every night, so…”

That’s the thing about talking with Klaus: he’s ventured down so many extreme paths in his life that one often struggles to keep up. What might be a shocking revelation for most people is, for him, just a throwaway. “Have you ever driven 1,500 kilometres, without any sleep, in the desert?” he asks at one point. (No, Klaus, I can’t say I ever have.) “I’ve been clinically dead for six hours,” he mentions later, almost in passing. What? Really? And he’s seen a brilliant light, and all the other things we hear about? “Life after death? Of course, I describe that in my book.” His life is so crowded that some things don’t even rate a mention. “I’ve survived so many times,” he says at one point. “The war in Israel, and I was going between the tanks, and…” he flaps a hand dismissively, not wishing to bore me with trifles: “These are other stories.”

He was born in 1945, just after the fall of Berlin (his birthday is actually today, May 15), and grew up in Germany, though he’s currently based in French Switzerland. His mother “gave me away” to the evil priest when he was 15, by which time he’d become unmanageable. “I was revolting against her, because my mother didn’t have love,” he explains. “I had a gang – I mean a robber gang – and we were breaking shops and stuff like that, and made gang wars between each other. I was un-educatable”. His father left the family when Klaus was a baby, leaving Mum to take care of him and his two brothers – but his mother, he recalls, “just could not stand me, and I could not stand her… I never had a family. I don’t know what it is to have a family, even nowadays.”

One brother left to join his father; the other stuck it out till adulthood, then fled to America and started a new life. Klaus lost touch with both of them, though he tracked down his dad in Stuttgart years later and was reunited with his brothers. “I forgave them later,” he asserts. “In the name of Christ it’s possible – otherwise I would kill them”. And what about his mother? Did he forgive her too? “I forgave her, but she was so possessed with demons. She was all the time full of demons.”

Real demons, or metaphorical?

“No, no, real demons. She called them, and she was influenced by them. And she was like crazy sometimes, it was terrible living with her.” Violent too? He nods: “She could beat me half to death sometimes. With a metal stick.”

All this rage came out in his gang of teenage hoodlums: they threw rocks, robbed people, even burned a man’s house down. “I was suffering,” he says now. “I just knew ‘do them bad’, because they did bad to me”. This was also when Klaus first realised he had power over people. “I found very quickly that I’m a leader… I just knew when I spoke to people, I was somehow convincing, and they followed me. So [I’d say] ‘Beat this guy up’ and they beat the guy up, you know?” In his early 20s, having finally escaped the clutches of the priest, he was studying Languages at the University of Tubingen – but was soon seduced by Andreas Baader, who was recruiting students for his “violent movement” aimed at the wholesale destruction of German society. Klaus, full of hatred, was ripe for the picking: “Police was enemy. Teachers were enemy. Priests were enemy. My mother was enemy. Everybody was enemy”. He pauses: “Because there was no love”.

It wasn’t just violence, he points out; there was idealism there too. “We really believed that we could change the world” – forgetting, he adds, that you first have to change yourself. “We thought we could do it by drugs and making love, free sex. [But] we ended up in passion instead of in freedom.” In any case, he soon discovered that “violence is not my way” – and also discovered that drugs only made things worse, amplifying his feelings of alienation instead of resolving them. At one point, he recalls, when he looked around at people “all their faces became skulls… I projected Death in everybody”. In any case, by the early 70s he’d “found a better drug: it was Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Transcendental meditation.”

Thus began his years of spiritual wandering. “I was an earnest seeker,” he tells me, though he must’ve seemed like a spiritual tourist, this half-crazy German plunging into one Eastern religion after another. Islam never appealed to him: “This is law, law and law. It didn’t give me love” – but he spent seven years exploring Hinduism, visiting all the great gurus in India (“I found very quickly they were often fakes,” he scoffs, “full of pride”), then three more years in Tibet as a Buddhist.

This is also where Klaus’ account of his life veers into claims that some will find incredible, like his description of the powers he wielded during those years – an extension of his old power as a gang leader, honed and perfected by years of meditation. “I could see people’s thoughts, what people think about” – not the precise thoughts but the “direction”, which he then manipulated. “I could make myself invisible. I started to hear voices from the beyond. I was a medium”. He had frequent out-of-body experiences. Dead gurus spoke to him, giving audible messages in English. “I had power. I was in New York and six gangsters wanted to kill me. And when I looked in their eyes, I could bind them. I had the power. When I had eye contact, I could just paralyse them”. Like hypnosis? It wasn’t hypnosis, he demurs, it was the power of the spirits. “I looked at people in the eyes, and when they were somehow not sure of themselves, I just got them somehow, I had power over them. Especially, in my case, for girls, of course – because you want to make sex. It’s not love, but it’s a substitute. Better to have substitute than to kill yourself.”

It’s not entirely implausible. Even now, at 66, Klaus cuts a striking figure: thin-faced, dressed in black, with close-cropped silver hair and narrow, unblinking eyes. There’s something compelling in those eyes, even if it’s just a hardness and lack of humour. Didn’t he ever have fun in those decades of wandering? Didn’t he ever just relax, maybe crack a joke? But he shakes his head: “No, it was lonely, it was very lonely. I was lonely all the time.”

Oddly enough, the person who impressed him most in India was a Christian – a religion he’d definitively abandoned after his years of abuse. That was Mother Teresa, whom he met in Calcutta: “She was my first mother,” he says poignantly. “The first person who had love for me, unlimited love. I thought such a person can not be a Christian – I even tried to convert her to Hinduism!”

Mother Teresa was the first step on the second part of Klaus’ journey – the journey back to Christianity, which of course is why churches invite him to share his experiences. It’s a journey that’s impossible to describe in detail without writing a book about it (as Klaus did), but it does include two crucial events which demand to be mentioned. The first was a miraculous escape in South America, when Klaus was abducted by Colombian rebels – who, realising they could get no ransom for him, decided to shoot him. Lying naked in a muddy ditch with seven rifles pointed at him, Klaus cried: “God, if You exist, save me now!” – and, right on cue, another rebel group emerged from the jungle, prompting a shoot-out with the first group and allowing him to flee in the confusion.

That was in 1981, just a few months before the second great miracle – when Jesus actually spoke to him, in a church in Lausanne. “Jesus,” asked despondent Klaus out loud, “do you want me to come to you or not?” – and Jesus, “as clear as you hear me now,” speaking French “in a sweet, indescribable voice”, replied: “Yes, come. I have forgiven you everything”. “And I was never touched so deeply,” he says quietly, “in my heart, in my being, as in that moment.”

There’s more, of course – much more. That communion with Our Lord was preceded by not one but two exorcisms (the priest in Lausanne insisted) and followed by what he calls a “counter-attack of Satan”. And I haven’t even mentioned all the other things, the miracle in the Syrian desert circa 1971, the George McGovern story, the levitation… I look at Klaus, unsure what to say. You do realise, I ask finally, that when I write this stuff in the paper, people will read it and say –

“Crazy man,” he agrees.

They won’t believe you.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

So what do you say to those people?

“Well, you are right not to believe it,” he replies, “because it sounds incredible. But I can not lie in the name of Christ – because I would condemn myself to Hell. And I lived in Hell. I don’t want to go back there.”

Maybe that’s the crux of it, when it comes to Klaus Kenneth. Mystics will say he found God, psychologists will say he found closure, but the story’s much the same whichever way you want to tell it: the story of a man who was raised without love, coldly and abusively – who “lived in Hell,” as he puts it – wandered for years trying to find inner peace, and finally found it.

It’s a quest for love, as he says again and again. It’s a quest for comradeship, which is doubtless what he found with Father Sophrony. ‘Why not just accept your life?’ I ask. Why even bring religion into it? Why not just accept human nature and say ‘This is life’?

“Because you feel that is not life,” he replies. “It’s a wrong life. That is what society calls life. But inside my heart, when I went to bed after my stories with alcohol, sex and whatever – I felt alone. And that is not life.”

Originally published in Cyprus Mail. Used by permission. Any reproduction of this publication online or in print requires written permission from the publisher, Cyprus Mail.