For a long time all the churches of Christendom, all the communities which singly proclaim their faith in the one God, have been separated from one another. For a long time they moved away from each other, and then they stopped and shyly, from a distance, looked towards each other. By then we were too far from one another to see the light in the eyes and the beauty on the face, the Image of the church that had ceased to be ours. Shyly again, moved partly by human sympathy, partly driven towards each other by God’s power, we have become closer. In coming nearer we have discovered human faces where we expected none any more, and in these faces we have begun to read, to rediscover the image of God. This is where we are now; we have come close and we can look into each other’s eyes, listen to one another’s words, draw nearer to one another’s hearts, measure the width, the depth and the breadth of each others intellectual achievements and minds. But this is not enough; we must learn to do more, and I wish to say a few words about the way in which we can do more.

People who wish to understand one another, to meet one another not only outwardly but in depth, must learn first of all to accept the existence of the other in his otherness. As long as the other is looked at and thought of as someone who happens to be there but should not be there at all, there is no meeting. And yet that is so often our attitude, not only among Christians but among people in general. The other one becomes acceptable to us when he becomes a replica of ourselves, an image of ourselves, when we begin to recognise ourselves in him. This is not a fair way of treating the other, neither is it a constructive or creative way of starting an encounter. We must each, as individual members of the churches and as the people of God broken up into separate bodies, learn to accept the other with all his otherness, not only in what makes him akin to us, but with what makes him profoundly different to us, indeed alien to us. Indeed inimical to us.

This acceptance of the other in our times, under the circumstances of our life, requires only integrity of mind and openness of heart, but there are circumstances and there were and still are times when accepting the other in his otherness implies danger for us: physical danger, intellectual danger, emotional danger; and we must face the fact and accept the danger. The other may hate us and wish for our destruction, the other may refuse the meeting and wish to wipe us off the map. Only if we are prepared not to change our attitude towards him, whatever he may do, will we treat him as Christians should treat the other. The Apostles give us a clear commandment: “Receive one another as Christ has received you.” Each of us is alienated from God, an enemy of his Cross estranged from the mysteries of love, and yet he receives us and is prepared to pay the cost of his love for us by his life and by his death. This is the first condition: to accept the existence of the other whatever the consequences for my physical or my inner security.

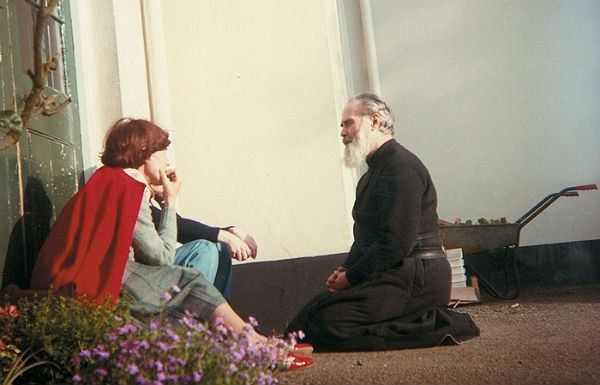

And when we have accepted the other as he is, we must learn to look at him and listen to him. We live in a world of men, we need one another continually, and we never see each other properly. If you think of one single day, how many people have crossed your path, how few have we looked at and seen? We run into each other, we cross one another path – we do not see each other. We must learn – and this is a training in inner discipline, in human attention, in concern – we must learn to look at every person who crosses our path, to look and see the features, the expression in their eyes, take in the whole person. And then how often it will happen that a perfect stranger will move us deeply by the anguish there is in his face, the fear, the insecurity, or on the contrary the joyous fragrance that emanates from him.

We must learn to see; we must also learn to hear. How often do people speak to us and we do not hear? Indeed, not only do we turn a deaf ear to what they are saying when we find it more convenient not to have heard, but how often all we hear are words and we do not even try to perceive – behind or beyond the words that may be clumsy, awkward, inadequate – a thought that may be alive and intense, worthy of man and of God» And beyond the thought, how seldom we pay attention to what the voice itself has got to say. How often does somebody say: “I’m all right,” and we accept what he ^as said because it is so convenient for us that he should be all right, for then we do not have to care, and we do not perceive that in those few words there was a shy appeal for compassion, for mercy – I am not speaking of love, it is too great a word – for sheer humanity.

We must learn to listen and to hear, to look and to see. To do that we must the same time learn to be close enough to the people concerned, and far enough. When you want to see a statue properly, or a painting, you do not come as close as possible. According to your eyesight, you come closer or stand farther away, and there is a point from which you can see all there is to see without your vision being blurred by details which are irrelevant and would make it impossible for you to receive the message. If you stand too far from a statue, you see a vague block of stone; if you come too near, you begin to see the details of the stone. In neither case will you see the statue nor perceive what the artist wanted to convey. We must learn in every single case, not in general but always, at every moment, with regard to every person, to find that distance which links us and makes it possible for us to perceive all there is to perceive and not to be blinded either by the blurring distance or the blurring details. And we must also learn to hear, not only by paying attention to the concrete words and to the mind behind and to the feeling that brings these words to life, but even more by an open-heartedness and open-mindedness that will allow us first to receive; to analyse, examine, think out and submit to scrutiny and criticism only later. Notice how often, when someone speaks to you, your mind keeps up a continual commentary, and while he is still speaking you have already formulated your answer. You have picked out, on the way, all the points against which you could speak or which you kindly, generously could approve of. What he meant to say may be irrelevant; you have found what to say.

Now in order to learn listening one must learn something about humility: not the kind of humility which we exhibit all the time, trying in a silly way to persuade everyone that we are of no account, trying to tell everyone whenever we chance to do something right, that of course it has no meaning, it is nothing, – only contradicting what common sense says and exhibiting not humility but sheer hypocrisy or stupidity. Humility is something else. The Latin word from which it stems speaks of the fertile soil. Humility is the state of the soil, of the earth. It is always there, always silent, always taken for granted. It never fails anyone. It is walked upon and trodden under everyone’s feet. All the refuse of the earth is poured out on it: whatever we do not need we cast out and throw onto the earth. It receives everything without a word, receives it, assimilates it and becomes rich from what we have cast away. But it also receives what God gives: the sunshine and the rain and the seed and the power to bring forth life. This is what we should be, so open in the face of the sky, so open in the face of God, so open before the face of men and, under their feet, always reliable, never letting anyone down, always silent and respectful, always capable of receiving what comes our way, receiving it and absorbing it and bringing forth fruit.

To do this we must learn something else again. We must learn to be free from this fierce concern about ourselves which gnaws at us, makes us the centre of all things. I would like to give you an example or an image taken from Charles Williams’ novel “All Hallows’ Eye.” He speaks to us of a girl who has died in an accident. At a certain moment of her life, between the earth which she has lost and eternity which she has not yet gained, she finds herself on the banks of the Thames. For the first time she sees the Thames with the eyes of a spirit; her body is already dead. When she had a body and saw the Thames, she had a revulsion against it. She saw the heavy, greasy, polluted waters carrying all the refuse of the great city of London. She had a revulsion because all her body responded to these waters with the feeling: “I could not wash in these waters, I could not drink from them.” All that reaction was centred on herself. Now she has no body which could respond with disgust and rejection to what she sees, and therefore she sees dispassionately, she sees these waters for a fact, and seeing them for a fact, she discovers that this fact is perfectly adequate. These waters are all they should be in order to be the great river that runs through the great city. And the moment she has accepted these waters for a fact in perfect harmony with the nature of the situation, she begins to see deeper and deeper layers of purer and purer water. Then she begins to perceive a light streaming from the depth, translucent first, transparent next, and then suddenly the miracle of a clear stream of water in which she, the dead girl, recognises the primeval waters which God created, and at the heart of this primeval water a fragrant, scintillating stream of living water, that water which Christ promised to the Samaritan woman. We see through layers of fragrance, decreasing light, decreasing translucence, heavier and increasing opacity. She saw things as we should see them, in depth, with eyes free from self. This is why she could see these things. And we must learn it, and we can learn it if we accomplish the first thing which I Indicated: if we accept the other as it is for a fact; if we realise that events and people have a right to be what we are not, that they have a right to be contrary to us, they have a right to be a scandal to us, they have a right to be a danger for us. They do not exist for us; they exist before the face of God, not before our face and our judgement, but for Him and for themselves, not for us only. If we do this, then we can begin to accept the other, listen to him with an open mind, see him with an open heart, discover him in depth as God sees him, with the image of the living God in him. And if we see this image disfigured, we will not then judge, condemn, reject; we will turn to this image with the veneration we pay to a sacred object which has been disfigured. Do we throw into a dustbin an icon of the Mother of God or the Saviour because it has suffered, or even the damaged photograph of someone dear to us? We should treat one another as an image of God disfigured. It is given to us to reverence it, to recognise it, to call out of the depth what is buried deep under the dust and the pollution. That we can do if we learn something about loving, because this kind of clairvoyance, of vision, we can have only out of love. Indifference sees nothing, hatred sees caricatures; only love can see the beauty of an ugly face, the image of God shining through the ugliness and the pollution.

If we begin here, with these few points, we will have begun something very important. We will then be able to meet one another. We will be able to hear unpalatable things, things which we dislike hearing, things which hurt. Then we will become able also not only to hear them but to speak them out because they are true, at least to ourselves, and we have no right to jeopardize our integrity in order to spare hurt feelings where it is God’s own truth which is at stake. But to do this we must begin very, very low in the simplicity of our ordinary life, because if we want to become workers of unity it is in the simple and humble things of life that we must learn it. A Russian priest said recently: “Only the Holy Spirit is great enough to appreciate the grandeur of things which are too small for men.” Yes, God does not discriminate between the great achievements and the smaller things. This is why he says to the faithful servant: “You have been faithful in little things; I will put you in command of the great ones.”

If we want now, from this very moment, to begin to become workers of unity, let us each, before the face of God and before the judgement of our own conscience, begin to become Christians. The unity of the Church will not be the unity obtained by diplomatic conversations and maneuvers of superficial or half-hearted Christians. The unity of the Church will be revealed in the verity of our lives and of our experience of God, of our life in God, of the life of God in us. It is in vain that we will toll to make ourselves one with each other if somewhere deep down we are men of division. Who can claim to be a worker of unity at large on the scale of the Church if he is divisive in the small unit which is the family, the workshop, the small society to which he belongs? Who can be a builder of unity who is a disloyal friend, an unfaithful spouse, a cruel, heartless and unfair employer, a disloyal and careless worker? Who can serve the Spirit of Truth who lies, the Spirit of Oneness when he divides by gossip, by slander, by calumny and so forth? We must learn in our personal and private lives to re-acquire integrity, to grow into oneness with one another, with the nearest, and in oneness with God who is nearer than the nearest, and gradually spread this miracle around us. Then we shall be able to become one, not as an achievement of human sagacity and cleverness, but because oneness will be restored within us.