I was speaking to an eighteen year old recently who told me about her bucket list: things she wanted to do before she dies. At the time, I didn’t think much about it. In fact, it seemed rather mature of her to have such specific goals. However, as I have thought about it, I’ve begun to suspect that having a bucket list is a symptom of a particular disease in our culture.

I have often heard people say things like, “God has something for me to do before I die.” It is as if the supreme cause to go on living is to accomplish “what God has for me to do.” It’s as if doing justified being, as if being were not enough, as if the Kingdom of Heaven were a matter of accomplishment. I suspect that such thinking is merely a religious reflection of a psychological need to justify our existence to ourselves.

This need to justify our existence manifests itself in several ways. For example, the bucket list assumes that one must “bag” experiences while one can. Each experience becomes a kind of possession, something no one can take away, something we have to show for our existence. It is as if your life consists in the abundance of the things you possess. The more experiences you bag, the more abundant your life, right? I don’t think so. At least that’s not the Gospel. Jesus said life does not consist in the abundance of things one possesses. What I do does not determine who I am; rather, who I am determines what I do. What that means is that no matter where I am or what my circumstances are right now, I can be myself, I can be my best self, and who I am will be reflected in what I do—regardless of how limited my options are. On the other hand, striving for a dream, I often create a nightmare. And even when circumstances work out just right for me to accomplish a long sought after goal, I wake up the next morning still myself. I wake up the next morning still me.

Once at a conference (and within two hours) I spoke with two women, both in their early 30s, and both frustrated because they were not able to bag the experience that they thought God was calling them to. The first was a single woman whose frustration lay in the fact that she loved children and wanted to be a mother—she was sure God wanted her to be a mother, but she couldn’t find a suitable husband. The other was a married mother of three, frustrated because she couldn’t “get out there” and serve the poor and needy as she was sure God was calling her. Both women were frustrated, both women were in a spiritual crisis, both felt as if God’s will in their lives was on hold, that they were treading water until their circumstances changed and they could finally do what they felt they were called to do, until they could bag the experience that had eluded them. And the experience of these two women is not very different from that commonly experienced by men who realize that they are never going to achieve their career goals, that for whatever reasons their options have closed in on them, that their identity can no longer be tied up in what they will do some day.

Back in my running days, I was a friend of Jim Ryun, the man who held the world record in the mile for about ten years. Jim used to talk about waking up the day after a big win frightened. Having bagged the big win or the great record, he had to do it again. That’s the problem with winning, with bagging experiences: once you climb Everest, there is always K-2. Possessions, even when those possessions are experiences, cannot define our life. Our life does not consist in what we posses. Our life consists in who we are and how we love God and how we love the people in our life right now. Our life consists in being, and in the doing that comes out of being.

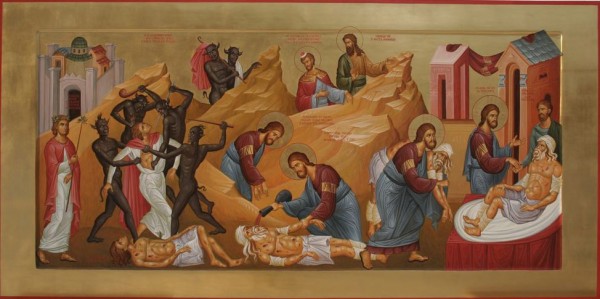

Isn’t that at least part of the meaning of the parable of the Good Samaritan—the one who shows mercy to the wounded man is the neighbour. Neighbour is who the Samaritan is, so mercy is what he shows. His deed manifests who he is; his deed does not make him who he is. The priest and Levite do not show mercy because mercy is not already in them. They were not neighbours so they could not be neighbours. The Samaritan did not become good because he showed mercy; he showed mercy because he was good.

This is a mystery. Both the Levite and the Samaritan knew what the right thing to do was. Both had other things to do—it is almost never convenient to show mercy. And yet one reveals himself to be good, not because he felt good or thought himself to be good (I’m sure both the priest and Levite thought themselves to be good, or at least good enough). The Samaritan reveals himself to be good not because he met his goal for the day or bagged an experience he had sought. The Samaritan manifests himself to be good because good is already in his heart and it is manifest in the circumstance he finds himself in.

The same mystery works in our lives, whatever circumstances we find ourselves in. What we do does not define who we are, it manifests who we are. Nothing hinders us for showing mercy and kindness. Nothing limits our ability to be patient, wise, humble or helpful. Married, single, parent, or prisoner, no circumstance is more or less suited for manifesting who we are, who we are becoming in Christ. Life does not consist in the abundance of possessions, experiences or even good deeds. Life consists in transformation, in loving God and neighbour, whoever that neighbour may be.