For me the role of philosophy in Christian faith has always been something like Anselm’s famous motto: “faith seeking understanding.” When applied to the faith, Philosophy is just faith seeking understanding, useful for synthesizing with reason those things initially accepted by faith. Philosophy offers the chance to know those things which the faith preaches.

Didn’t St. Paul say to always be ready to “give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope you have” (1 Pet 3.15)? Give a reason! the apostle says. What better way to give a reason than to prove the faith through philosophy? Knowing the truth “will set you free” (Jn 8.32). These and other scriptures convinced me that Christianity needed as much input from philosophy and science as possible to shore up the faith (if not for believers, then certainly for nonbelievers).

Until recently I didn’t realize the troubles I was unwittingly stepping into with this. The troubles are serious and easily result in a complete undoing of faith. The above is nothing short of the difference between “I believe in one God” (the Nicene Creed) and “I know there is one God.” The difference in these two statements is immense, and there is good reason why the Church Fathers thought in terms of the former and not the latter.

Lev Shestov had this to say in his profound book, “Athens and Jerusalem”:

The apostle contented himself with faith, but the philosopher wished more—he could not be content with what preaching brings him (‘the foolishness of preaching,’ as St. Paul himself puts it). The philosopher seeks and finds ‘proofs,’ convinced in advance that the proven truth has much more value than the truth that is not proven… Faith is then only a ‘substitute’ for knowledge, an imperfect knowledge, a knowledge—in a way—on credit and which must sooner or later present the promised proofs if it wishes to justify the credit that has been accorded to it.

A common thought-approach to faith goes something like this: Faith is for children, knowledge for the mature. As God commands the ignorant to obey by faith, parents command their children to likewise obey. But the expectation is that eventually knowledge replaces child-like faith as we mature into adults, into gods. Knowledge saves.

Few Christians would actually admit this, the belief that faith is a “substitute” for knowledge “on credit” waiting for real knowledge to fill in the gaps. They recognize its gnostic vibe immediately and reject it. But the rejection is not full—it’s just intellectual—as evidenced by the way we actually live. To admit that knowledge saves is the same as admitting that the tree of knowledge grants life, not death. That is, that God, and not the serpent, was the great deceiver in the Garden.

Are we still deceived by the ancient lie? I’ve thought it in my heart a thousand times, “Dammit Adam, why were you such a fool to believe the lie and condemn mankind to death and suffering?” But what did Adam believe but that knowledge grants beauty, wisdom, and theosis. Every last one of us have repeated his fall. We all believe that knowledge saves regardless of the fact that we have no evidence of progress but only of the fall (G.K. Chesterton).

Shestov asks, “Is it not clear that we are in the power of that terrible, hostile force of which the Book of Genesis speaks to us?” Attempting to resolve faith with knowledge, as our first parents did, has not led to enlightenment, paradise, or godhood, but their opposites.

And this isn’t to disparage knowledge in general, but rather to disparage that sly, psychological faith in knowledge that creeps into the Christian psyche, promising deliverance from the struggles inherent in faith—struggles necessary for salvation.

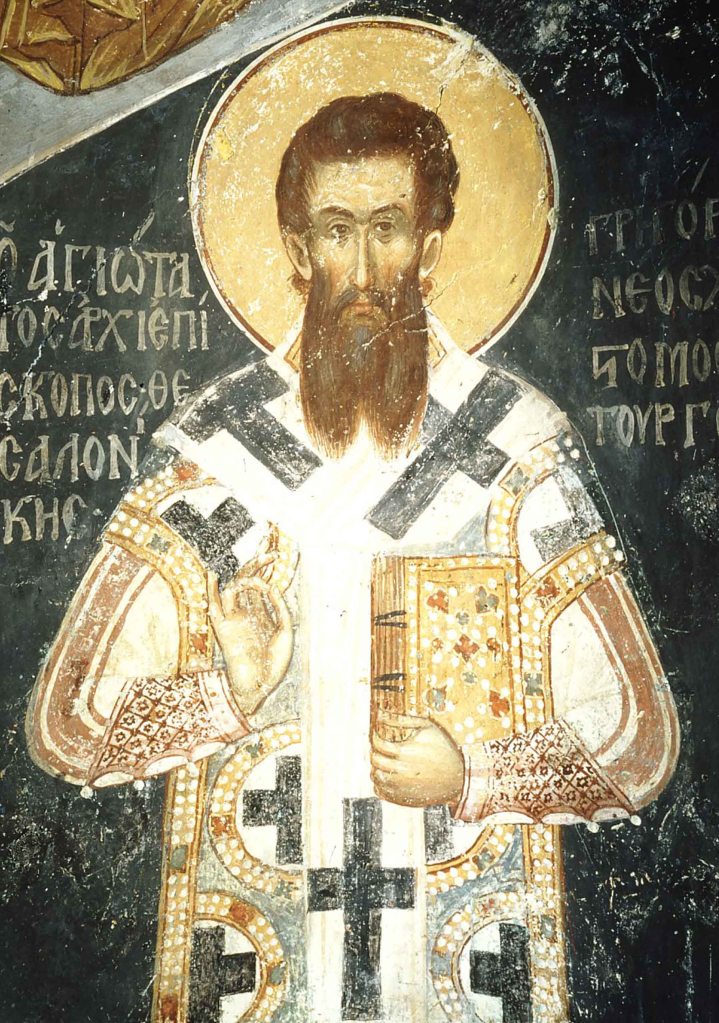

A disciple of St. Gregory Palamas once approached him saying, “I have heard it stated by certain people that monks also should pursue secular wisdom, and that if they do not possess this wisdom, it is impossible for them to avoid ignorance and false opinions… and that one cannot acquire perfection and sanctity without seeking knowledge from all quarters, above all from Greek culture.” The disciple grieved that he had no answer to these people and desperately sought one.

St. Palamas responded first by acknowledging that people have indeed always arrived at concepts of God using these means, but their best attempts could only produce worship of demons and inanimate objects, and systems of polytheism. They in no way could arrive at the “truth” no matter their genius. But “just as there is much therapeutic value even in substances obtained from the flesh of serpents… so there is something of benefit to be had even from the profane philosophers—but it is somewhat as in the mixture of honey and hemlock.” Good luck at separating the two. Dividing correctly is a true gift: “but to divide well is the property of very few men.” He even notes an example of the then “iconognosts” who “pretend that man receives the image of God by knowledge, and that this knowledge confirms the soul to God.” This is a very ancient yet very modern idea, and it is thoroughly refuted by scripture and the Church. Knowledge does not save.

St. Palamas continues his response explaining that even Adam who possessed natural wisdom in abundance more than all his descendants failed through knowledge to safeguard conformity to the image of God. “Profane philosophy existed as an aid to this natural wisdom before the advent of Christ…Why then were we not renewed by this philosophy before His coming? Why did we need, not someone to teach us philosophy… but One ‘who takes away the sin of the world’?”

After these and several other demonstrations of the failures of knowledge to deliver the goods it promises, St Palamas finishes with this:

If a man who seeks to be purified by fulfilling the prescriptions of the Law gains no benefit from Christ—even though the Law had been manifestly promulgated by God—then neither will the acquisition of the profane sciences avail. For how much more will Christ be of no benefit to one who turns to the discredited alien philosophy to gain purification for his soul?

Though this is a fitting place to end, I cannot resist one more example from the Gospel of John. All things considered, one needs proceed no further than Pontius Pilate. That famed pagan—representative of the combined wisdom of secular thought—stood before the Truth (Christ) and asked, “What is truth?” And immediately turned and crucified it.

There’s a lesson in there.