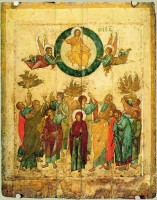

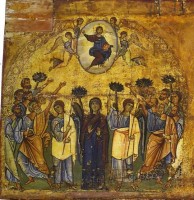

If one read the four Gospels as if they were four separate biographies of Jesus, one might be forgiven for thinking that the Ascension narrated the end of the story. We have read narratives of Christ’s birth, His baptism, His temptation in the wilderness, His ministry, His crucifixion, His resurrection, and now at the last we come the narrative of His ascension, concluding the story of His life with a heavenly happy ending. Everyone loves a happy ending, and this one rounds out the story of Jesus by saying in effect, “And He lived happily ever after at the right hand of God.” In this way of thinking, the story is not finished without the Ascension.

It might therefore come as a surprise to learn that three out of the four canonical Gospels do not end with the Ascension or even narrate it at all. Matthew’s Gospel ends not with Christ ascending from us, but with His remaining with us, uttering the words,

“Behold, I am with you always, even to the close of the age” [Matthew 28:20].

The authentic ending of Mark’s Gospel ends with the discovery of the empty tomb (the last part of Christ’s public ministry, just as His baptism was the first part), and with the words that the women “fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” [Mark 16:8]. John’s Gospel ends with a third appearance of the risen Christ to His disciples by the Sea of Tiberias (scholars debate about whether or not it first ended with the earlier appearance to Thomas) and with John’s observation that if everything Jesus had done were to be written up, the world itself could not contain those books. John clearly knew about the ascension, for he records Christ’s words to Mary Magdalene, “Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to My Father” [John 20:17], but he does not narrate that ascension any more than Matthew does or Mark does. Only Luke narrates the ascension, adding almost as an afterthought that “while He was blessing them, He went away from them and was carried up into heaven” [Luke 24:51], the ascension event itself expressed in a mere five words in the Greek. Luke narrates it at somewhat greater length in his second volume, the Acts of the Apostles, saying with a similar economy of words, “while they were looking, He was taken up and a cloud received Him from their eyes” [Acts 1:9] — the event expressed in nine Greek words. What does all this mean?

For one thing it means that the Gospels are not biographies as we understand the term. But more importantly it reveals that the ascension was not the ending of a story, but the beginning of one, not the conclusion of Christ’s life so much as the beginning of the life of the Church. It is no coincidence that the Evangelist who narrated the ascension also narrated at great length and repeatedly the coming of the Holy Spirit on the Day of Pentecost, so that Luke is the Evangelist of the Holy Spirit as well as the Evangelist of the Ascension. The two events are connected, for one is the cause of the other. Christ foretold it during His last night with His disciples prior to His arrest: “It is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Comforter will not come to you; but if I go, I will send Him to you” [John 16:7]. Luke narrated the fulfillment in the words of Peter’s Pentecostal sermon: “Being exalted to the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, He has poured out this which you both see and hear” [Acts 2:33].

The temptation is to regard the Holy Ascension as if it were the Holy Absence, as if Christ has gone away and we now have less of His presence than was available when He walked the earth. It is not so. While He walked the earth, the apostles could be with Him, but this nearness was conditioned by time and space, and there were times when they were not with Him. When He was not physically in Judea, for example, Mary and Martha could not be with Him. Now that He has been exalted to the Father’s right hand and has sent His Spirit, we can be near Him always, for His presence is no longer conditioned by time and space. Everyone can now be close to Jesus and by the power of the Spirit can be with Him every waking hour and even every sleeping hour. The ascension and the sending of the Spirit means that we now have more of Jesus, not less of Him. That is why the Lord said at the end of Matthew’s Gospel that He would be with us until the close of age. These words were not a denial of a future ascension, but a promise of it. The challenge for us now is to live as children of the ascension, and as children of the Spirit. Our Lord’s presence and power are always available to us. The question is: how often do we avail ourselves of them?