Source: Orthodox World

Understanding icons may be difficult due to a special way of conveying space and the beings and objects inside it.

We look at pictures with the eyes of a European, and what we see in them seems to resemble what we see around. ‘Verisimilitude’ in European painting is achieved by using linear perspective. The teaching that deals with perspective was born in the XIII century and played an important role in European culture.

The first to create an illusion of the three-dimensional space on a plane was Giotto (1267-1332).

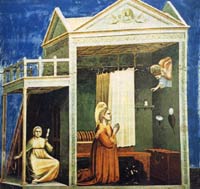

We may use his frescoes as an example ‘Annunciation to Anne’ and ‘The birth of Mary’ (1305-1313). Joachim and Anne, the righteous couple, did not have children. Once an angel appeared to Anne and announced to her that she would have a daughter, the future Mother of God. And Anne gave birth to Mary. Let us see how Giotto reproduces those events. The interior of Anne’s house is drawn correctly from the point of view of geometry. The action was meant to take place inside the building. Before Giotto there had been no interior in pictures, frescoes and icons. A building, or a hill with a cave, served as a background for the characters. To show the interior the wall closest to the spectator in Giotto’s fresco is removed. Showing the interior in such a manner was a great innovation introduced by Giotto. He dared to step aside from the tradition of conventional painting. Judging by the size of the objects (the bench, the chest) we can imagine the size of the room where the action takes place.

We may use his frescoes as an example ‘Annunciation to Anne’ and ‘The birth of Mary’ (1305-1313). Joachim and Anne, the righteous couple, did not have children. Once an angel appeared to Anne and announced to her that she would have a daughter, the future Mother of God. And Anne gave birth to Mary. Let us see how Giotto reproduces those events. The interior of Anne’s house is drawn correctly from the point of view of geometry. The action was meant to take place inside the building. Before Giotto there had been no interior in pictures, frescoes and icons. A building, or a hill with a cave, served as a background for the characters. To show the interior the wall closest to the spectator in Giotto’s fresco is removed. Showing the interior in such a manner was a great innovation introduced by Giotto. He dared to step aside from the tradition of conventional painting. Judging by the size of the objects (the bench, the chest) we can imagine the size of the room where the action takes place. Giotto seems to use transparent cubes to build the space in his frescoes. This is the first and most important step towards arithmetizing space. In the seventeenth century the French philosopher and mathematician Rene Decartes (1596-1650) laid the foundations of analytical geometry which, but for Giotto’s discovery, would have been born much later.

Giotto seems to use transparent cubes to build the space in his frescoes. This is the first and most important step towards arithmetizing space. In the seventeenth century the French philosopher and mathematician Rene Decartes (1596-1650) laid the foundations of analytical geometry which, but for Giotto’s discovery, would have been born much later.

Let us look at Giotto’s frescoes again. The angel is flying in through a small window. An angel, having no flesh, needs no window to get inside a room. But Giotto’s angel does not just fly in through the window but squeezes through it, acquiring almost physical materiality. In such a way Giotto brings the miracle ‘down to Earth’, trying to make it look trustworthy.

Translation of Christian Tradition into the language of earthly images and the discovery of linear perspective marked a new age in European art – the art of realism.

However, people who created icons had quite a different attitude toward space. The space ‘not of this world’ is usually conveyed in icons by golden background; objects and their location in relation to one another are given in the so called reverse perspective.

Let us try to explain the nature and properties of reverse perspective which is older than linear perspective. Icon-painters knew the fact that human eyesight is imperfect and cannot be trusted because it belongs to the flesh. Therefore they reproduced the world not as they saw it but as it really is. They did not use the experience of their earthly life but the dogmas of the faith. The authors of the first written works on linear perspective Ibn Al Khaisam and Z. Vitelo considered the decrease of the size of objects moving away from the spectator to be an optical illusion. But linear perspective geometry (reproducing this ‘optical illusion’) was convenient and was eventually mastered by European artists.

As for Orthodox icon-painters, they remained true to reverse perspective.

As for Orthodox icon-painters, they remained true to reverse perspective.

As has already been already mentioned, an icon is a window facing the holy, sacred world which opens to a person looking at the icon. Space in that world has properties different from those of the space on Earth; properties unseen by physical eyes and inexplicable through the logic of this world.

The picture shows how the expanding space is constructed. Here appears the reverse perspective: objects also expand moving away from the spectator.

However, artists could not stick to the scheme strictly, as the world in icons is just represented – by symbols of objects and people, – so one can often see ‘mistakes’ in icons.

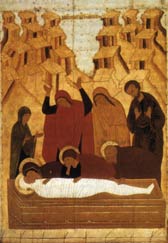

Reverse perspective and its properties are vividly expressed in the ‘Laying in the Tomb’ icon. In the foreground there is the tomb with Christ’s swaddled body in it. The Mother of God is bending over it, pressing her face to her Son’s face. Next to her the Teacher’s beloved disciple – st. John the Theologian is bending over the body. He looks into Jesus Christ’s face with sorrow, propping up his chin with his hand. Behind St. John there are Joseph of Arimathea and Nikodemos standing still in sadness. To their left there stand the myrrh-bearing women.

The sorrowful scene is laid against the background of ‘icon hills’, drawn using the technique of reverse perspective – they expand radially as they move away from the spectator.

Reverse perspective produces an extremely powerful effect here: the space ‘unfolds’ in all directions – up and down, to the sides and deep inwards so that everything that takes place in the icon acquires a cosmic scale. Mary Magdalene’s raised hands seem to connect the place where the Lord’s tomb is with the whole Universe.

The shroud shining with unearthly whiteness immediately draws the spectator’s attention to Christ’s body wrapped in it but the details of St. John’s and Mary Magdalene’s clothes look like dark flashes directed upwards against the background of Mary Magdalene’s bright-red garment. The flashes make the spectator’s eyes follow her tragically raised hands and look upwards towards the other world.

But the edges of the icon hills converge at the coffin, letting one’s eyes go back to the body of Christ – the center of the Universe.

This laconically expressive icon is a model of a still, lamenting prayer; its sad words have acquired shape and colour on an icon board…

Reverse perspective does not result from the artists’ inability to reproduce space. Old Russian icon-painters rejected linear perspective when they came to know it. Reverse perspective retained its spiritual meaning and represented a protest against the temptations of ‘physical eyesight’. Besides, using reverse perspective often had some technical advantages: for example it allowed to turn buildings in a way that opened to sight details and scenes ‘screened off’ by the buildings.