My question is about humility. What does it mean to “regard oneself as the worst of all”? Does that mean to regard oneself as the dullest, ugliest, and most miserable of all? Could you please explain? ~ Irina.

Archpriest Alexander Iliashenko replies:

Archpriest Alexander Iliashenko replies:

Dear Irina,

Regarding oneself as the “dullest, ugliest, and most miserable of all” does not mean being humble. If someone actually is smart and attractive, he will never sincerely be able to regard himself as dull and ugly.

One must understand and remember that intellect, beauty, and health are completely unearned gifts of God. Consequently, they are nothing to be proud of. If you are more attractive than your neighbor, that does not mean that you are better than him; you should not therefore regard your neighbor as worse than yourself. In other words, humility does not mean belittling and deriding your own merits; rather, it means remembering that your neighbor, even if he is not as attractive or smart as you, is still a beloved child of God – and that you should relate to him accordingly.

There are very few humble people. It can be stated that a humble person is a holy person, because being at peace with God means that we are overcoming our sins. Sin alone separates us from God; when we have peace within, that also means we have no sins.

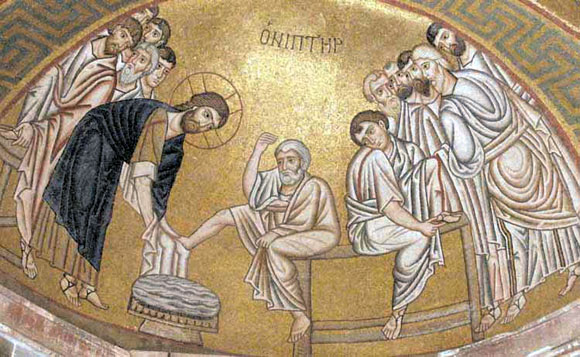

A humble person becomes like God. The Lord said: I am meek and lowly in heart [Matthew 11:29]. The saints transcended human nature, becoming like God. [1] Attaining this likeness without humility is impossible. Scripture says: God resisteth the proud, but giveth grace unto the humble [James 4:6; 1 Peter 5:5].

C. S. Lewis gives a very good description of the difference between real and sham humility in The Screwtape Letters. These are letters written by an experienced demon (Screwtape) to his young nephew (Wormwood) with advice on how to tempt people and lead them away from Christ.

There is a remarkable section in the fourteenth letter that explains the essence of humility in simple and comprehensible language. (I should point out that, inasmuch as this correspondence is between demons, the Lord here is called the Enemy and everything that is described as good is in reality harmful for man, and vice versa.)

My dear Wormwood,

The most alarming thing in your last account of the patient is that he is making none of those confident resolutions which marked his original conversion. No more lavish promises of perpetual virtue, I gather; not even the expectation of an endowment of “grace” for life, but only a hope for the daily and hourly pittance to meet the daily and hourly temptation! This is very bad.

I see only one thing to do at the moment. Your patient has become humble; have you drawn his attention to the fact? All virtues are less formidable to us once the man is aware that he has them, but this is specially true of humility. Catch him at the moment when he is really poor in spirit and smuggle into his mind the gratifying reflection, “By jove! I’m being humble,” and almost immediately pride – pride at his own humility – will appear. If he awakes to the danger and tries to smother this new form of pride, make him proud of his attempt – and so on, through as many stages as you please. But don’t try this too long, for fear you awake his sense of humour and proportion, in which case he will merely laugh at you and go to bed.

But there are other profitable ways of fixing his attention on the virtue of Humility. By this virtue, as by all the others, our Enemy wants to turn the man’s attention away from self to Him, and to the man’s neighbours. All the abjection and self-hatred are designed, in the long run, solely for this end; unless they attain this end they do us little harm; and they may even do us good if they keep the man concerned with himself, and, above all, if self-contempt can be made the starting point for contempt of other selves, and thus for gloom, cynicism, and cruelty.

You must therefore conceal from the patient the true end of Humility. Let him think of it, not as self-forgetfulness, but as a certain kind of opinion (namely, a low opinion) of his own talents and character. Some talents, I gather, he really has. Fix in his mind the idea that humility consists in trying to believe those talents to be less valuable than he believes them to be. No doubt they are in fact less valuable than he believes, but that is not the point. The great thing is to make him value an opinion for some quality other than truth, thus introducing an element of dishonesty and make-believe into the heart of what otherwise threatens to become a virtue. By this method thousands of humans have been brought to think that humility means pretty women trying to believe they are ugly and clever men trying to believe they are fools. And since what they are trying to believe may, in some cases, be manifest nonsense, they cannot succeed in believing it, and we have the chance of keeping their minds endlessly revolving on themselves in an effort to achieve the impossible. To anticipate the Enemy’s strategy, we must consider His aims. The Enemy wants to bring the man to a state of mind in which he could design the best cathedral in the world, and know it to be the best, and rejoice in the fact, without being any more (or less) or otherwise glad at having done it than he would be if it had been done by another. The Enemy wants him, in the end, to be so free from any bias in his own favour that he can rejoice in his own talents as frankly and gratefully as in his neighbour’s talents – or in a sunrise, an elephant, or a waterfall. He wants each man, in the long run, to be able to recognise all creatures (even himself) as glorious and excellent things. He wants to kill their animal self-love as soon as possible; but it is His long-term policy, I fear, to restore to them a new kind of self-love – a charity and gratitude for all selves, including their own; when they have really learned to love their neighbours as themselves, they will be allowed to love themselves as their neighbours. For we must never forget what is the most repellent and inexplicable trait in our Enemy; he really loves the hairless bipeds He has created, and always gives back to them with His right hand what He has taken away with His left.

His whole effort, therefore, will be to get the man’s mind off the subject of his own value altogether. He would rather the man thought himself a great architect or a great poet and then forget about it, than that he should spend much time and pains trying to think himself a bad one. Your efforts to instil either vainglory or false modesty into the patient will therefore be met from the Enemy’s side with the obvious reminder that a man is not usually called upon to have an opinion of his own talents at all, since he can very well go on improving them to the best of his ability without deciding on his own precise niche in the temple of Fame. You must try to exclude this reminder from the patient’s consciousness at all costs. The Enemy will also try to render real in the patient’s mind a doctrine which they all profess but find it difficult to bring home to their feelings – the doctrine that they did not create themselves, that their talents were given them, and that they might as well be proud of the colour of their hair. But always and by all methods the Enemy’s aim will be to get the patient’s mind off such questions, and yours will be to fix it on them. Even of his sins the Enemy does not want him to think too much: once they are repented, the sooner the man turns his attention outward, the better the Enemy is pleased.

Your affectionate uncle

SCREWTAPE

Here is another wonderful example, from Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh:

I remember a pretty young woman in her early twenties came to me, sat down, and said with a dreadful expression on her face:

“I cannot be saved. I’m perishing of vanity!”

“And what are you doing to overcome it?”

“I don’t know what to do with it. I’m fighting against it, but the vanity is stronger than I am.”

“What causes you to be vain?”

“Every time I see myself in the mirror or see my reflection on the windowpane I think: ‘How pretty I am!’”

I smiled and said: “You know what? It’s true!”

She looked at me in horror and cried out: “Then what should I do? I’m ruined!”

“No, you’re not ruined. You need to learn to change your vanity into gratitude. Neither you nor I are yet on the path to humility. We don’t know what humility is – it is an attribute of the saints. But gratitude is something that we – each one of us – can acquire at any moment.”

“But how is it acquired?” she asked.

“Here is what you should do: Stand before the mirror three times a day and list all your facial features that you like: forehead, eyebrows, lips, nose, cheeks – in short, everything good that you can see in yourself. When you’ve finished, say: ‘Lord, I thank Thee for giving me all this, because I did not create this in myself.’ Then add: ‘And forgive me, Lord, that onto this beauty that Thou hast given me I am putting on this revolting expression that I now have on my face.’”

I think this can also be applied to spiritual attributes. The “poor in spirit” are those who recognize that everything they have comes from God. And instead of renouncing and denying it for the sake of acquiring false humility, they accept it, turning to God with gratitude for having given it to them.

Humility is a gift from God to those who sincerely desire to receive it and who pray for it to the Lord from the depth of their soul.

Humility means being at peace with God in any circumstances, even the most extreme; a humble person is one who always overcomes evil, but only with good, as the Apostle Paul writes: overcome evil with good [Romans 12:21].

Translator’s note:

[1] The word here translated as “saints” is prepodobnye, the title conventionally given to monastic saints, which literally means “most like”; the implication being that they have attained great likeness to God.

Translated from the Russian.