In a part of America that is rich with historic Orthodox churches, a new one, faithful to the local architectural tradition, is now under construction.

In the spring of 2018 I travelled to Spruce Island, where St. Herman of Alaska lived from 1808 until his death in 1837. I had come to design a new chapel for Saint Michael’s Skete. This small monastic brotherhood (a dependency of the monastery at Platina in California) occupies a remote site high up a mountainside. Founded in 1983, the skete has several monastic buildings able to host a handful of monks and summer visitors, but only a tiny house chapel. Fr. Andrew (Wermuth), the superior, felt that the time had come to build a large freestanding chapel.

This project presented two challenges for me, which I do not normally encounter when designing Orthodox churches in America. One is the difficulty of access for construction. Materials can be brought in only by boat, and then hauled up the mountainside with great difficulty. So the church would have to be built entirely of wood (even the foundation), and most of the wood would need to be milled on site from the abundant spruce trees.

The other difficulty was how to connect with the local history and traditions of Russian church building, while also differentiating it from any of the nearby historic churches. The historic churches of Alaska are a great cultural treasure, and provide a wonderful basis for design. But many of them are quite similar looking, and the monks were keen to have their new church be recognizable – something a bit different from the others.

There are two historic churches on Spruce Island: the Church of Sts. Sergius and Herman of Valaam, built in 1895, over the grave of St. Herman; and the Church of the Nativity of Christ, in Ouzinkie Native Village, built in 1906. Both are simple in form, fairly plain, but refined and elegant in their details and craftsmanship. In this they stand out from more recently built structures on the island, which tend to be ramshackle and utilitarian.

As I studied Alaskan churches, I saw this pattern again and again. The historic Russian churches are often the only building in a village that exhibits architectural design at all. And some of the most remote churches, in the most unlikely settings, are astonishingly elegant. They exhibit perfectly correct neoclassical detailing that would not be out of place on a fine building in Saint Petersburg. How remarkable to see beauty of this kind on remote islands, windswept and treeless, where even a small fishing shack seems like a heroic defiance of nature!

I think that the Russian missionaries and their native flock must have seen this architectural elegance as a sort of offering, a sacrifice of the best they could give to God. It parallels their admirably stubborn devotion to maintaining the faith exactly as they received it from Russia, never considering in worldly terms how difficult or unlikely this cultural marriage would be.

So I felt from the start that this was not a project where I wanted to relax and just design a practical rustic chapel – something appropriate for a remote mountaintop where few would ever see it. It would need to be that, but it would also need to be high art – serious architectural design in the neoclassical style – the style brought to Alaska in the days of the Russian Empire.

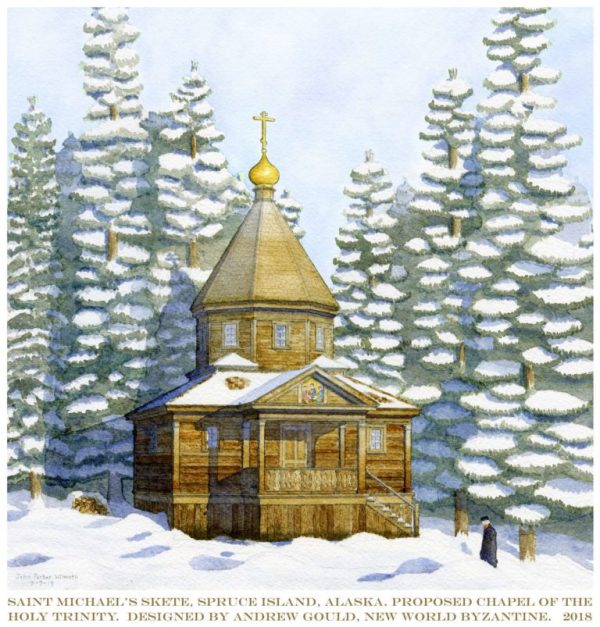

I spent several beautiful days at the skete, considering the design. The monks had imagined building their chapel right next to the main house, on some low flat ground. But I suggested they should build it a short distance away on top of a knoll, where it would overlook the monastery buildings and the sea. When we settled on this site, we felt it should be a tall design – almost a spire amongst the trees, to celebrate the beauty of worshipping God on a mountaintop. The site led the monks to decide that the chapel would be dedicated to the Holy Trinity.

After trying a number of architectural forms, I remembered that I had years ago seen a church in Novgorod – a sixteenth-century ‘tent’ church of the simplest possible form – an octagonal spire rising from a square base. This form proved to be the basis of a most successful design. The broad square base gives space for sacristies, choirs, firewood, and coats. The tall center makes for a triumphant nave. The tent roof would pleasingly complement the towering spruce trees.

I drew up a plan that would comfortably accommodate a dozen monks and a dozen visitors, and styled it with the paneled interior, lap siding, and the neoclassical trim of the historic churches. We all felt that this perfectly achieved our goals – a church that is recognizably Russian-Alaskan, but does not resemble any existing Alaskan church.

Back at my office, I worked to draw complete construction plans. I was careful to detail as much as possible in a way that the monks could build using their own timber. And I put considerable thought into making the structure as rigid as possible to withstand the intense winter storms. Fortunately the monks are capable builders, having built and maintained many of the structures on Spruce Island. They are undaunted by tasks that would not normally be attempted without trucks and cranes.

As of May 2019, construction has started. I will be updating this article with new photos as I receive them.

Those who would like to contribute to the project, or visit the monastery, should write to the monks at:

Saint Michael’s Skete

P.O. Box 90

Ouzinkie, AK 99644