Fr. Andrei Tkachev

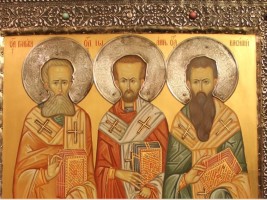

There are people about whom we say: “He has hands of gold.” There are far fewer people (although there are some, glory be to God) about whom we say: “He (or she) has a heart of gold.” But there is only one person to whom words once spoken in a burst of enthusiasm have become attached for all time: “He has a mouth of gold.” This was the Archbishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom – or, as we might put it, the Golden Mouth.

I do not know if John had hands of gold. Probably not. Having been brought up in worldly prosperity, he was afraid when choosing the monastic life that he might have to carry heavy loads, chop wood, or wear himself out through some other kind of physical labor. It seems as though he did not have hands of gold in the same way we might say a skilled carpenter or stonemason does. But he also had to have a heart of gold.

I say he “had to have,” because neither Demosthenes nor Cicero was ever called a “golden mouth.” No one will deny the civic virtue and sharp wit of these orators of antiquity. But no one would say that their hearts burned as brightly as their speech. Chrysostom could not turn his mouth to gold before he had gilded his heart. For the Savior said: for out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh [Matthew 12:34]; and the Psalmist says: My mouth shall speak wisdom, and the meditation of my heart shall be of understanding [Psalm 48:4]. As such, the mouth and the heart are inextricably linked. Foolish is the preacher who learns rhetorical devices without prayer; who seeks external means of eloquence without weeping in secret for himself and his flock; who puts his hope in syllables rather than in the Spirit that sanctifies these letters! Chrysostom had a heart of gold, and this would have been the case even if he had been mute. Fortunately, however, he did speak: the wealth of his heart was clothed in the flesh of the spoken word. The words brought forth from the golden treasure of his heart sanctified the mouth that uttered them. Thus was the possessor of this mouth given the name of Chrysostom.

+++

Where to start in singing the saint’s praises? From the maternal womb that gave birth to a single son? But what a son! From the nights spent pouring over books and the monastic labors that forever undermined his already fragile health? But why praise the saints in the first place? Has the Lord not already praised them – and continues to praise them – better than we can? It is better to seek to draw the great man’s image closer to ourselves, so as to plant ourselves, in all our darkness, under the judgment of his radiance. For indeed, the saints shall judge the world [1 Corinthians 6:2]. So let them judge it even now! Let them judge before the Judgment so that we, having been shamed by this preliminary judgment, might be spared the withering final Judgment.

May all who love the archpastor from Constantinople, and all who frequently serve the Liturgy bearing his name, forgive me. May they forgive me, for I wish to say that if Chrysostom lived in our days, he would be deposed and banished now, just as he was many centuries ago. And, I would like to add, it would be we ourselves who would depose and banish him.

He was not reconcilable to any falsehood; he was hot-tempered, principled, and fearless. Such people are more easily loved from the distance of centuries. In close proximity, it is easier to hate them. It is the same with a snowy mountain landscape, which is enjoyed when viewed through the window of a warm hotel room. But to enjoy snow-covered mountains up close means putting oneself at risk of falling into a precipice, of getting frostbit, or of losing one’s way.

Chrysostom set forth his understanding of the priesthood, his view of this ministry, in six discourses. When the priests themselves familiarized themselves with this teaching, they suddenly realized that one of two things must be true: either there were no priests in the capital, or else Chrysostom was wrong. This was the age of monarchy. But in moral questions, as always, democracy reigned. Democracy in moral questions means that right is decided not by whoever is actually right, but by whoever happens to be in the majority. Chrysostom, although the Patriarch, was in the minority. And the offended majority harbored a grudge against him.

He did not suffer from an excess of sensitivity when it came to questions of corporate ethics. Himself partaking of pea soup and almost nothing else, he offered pea soup to his guests – and nothing else. Loving silence and reading more than vain pleasures, he offended the way of life of the entire court and of almost all the clergy in the capital. From the very beginning, his banishment was just a matter of time.

Did he know this himself? He probably did. Therefore he hastened to accomplish the work of his ministry and looked at each new day of labor with gratitude. God gave him fiery, deep, purifying words. This was not in reward for the diligent study of rhetorical devices. God gave John words because John gave God his heart. He looked upon the ministry of the word as the Church’s only means of force. “How do we win over the ignorant and heretics?” asked John. “By miracles? They are long gone. Signs? But we have long been bereft of their power. Then how? By words!”

Does he not pass judgment on us today by this utterance alone? And would we, who seek miracles and preach lazily, really forgive him for such words?

+++

Money is for the poor. The heart is for God. Physical strength, talents, and life itself are for service. It is worth meeting a person like him: compared to him, many would whither away and become like wax dolls. If only they really were nothing but wax dolls! But they are alive, and whisper amongst themselves, and set their traps; like the serpent in Genesis, they “bruise the heel” of the righteous man. The good man himself is unconcerned. He is neither cunning nor silent, nor does he hide himself. It is as if he were looking for trouble; he makes mistakes and severs his last ties with people who could defend him. Let us make room for historical truth: John broke the rules. He allowed himself to ordain a deacon at Vespers rather than at the Liturgy. He intruded with his powers of authority into a foreign region and there deposed bishops who had been placed there for money. He deposed those over whom he had no canonical authority. He did much more of the like that seemed defiant, unprecedented, impudent, and worthy of retribution.

Retribution came, as did exile – first one, then the other. Then came death, far from cathedra and home. Obscurity should also have come. But suddenly, contrary to all expectations, people began to understand and appreciate John. Some still whispered that “if John is a bishop, then Judas is an apostle,” but others had already begun to see how much John had brought into the treasury of the Church. Time removed the blindfolds from those who had condemned John “for company’s sake.” Time softened the hearts of those who had been deceived by the malicious whispering. Time swept from life the souls of his implacable enemies. And then, from this historical distance, that majestic summit called Chrysostom began to come into view. It appeared where those with a myopic view had only just seen nothing but cold, ice, and rocks. From that time until the present day, this summit has continued to grow in size and to astonish by its unassailable beauty.

+++

How good that we live so far from Chrysostom’s times! Living where we do, we can make happy use of his treasures, drink from the springs of his teachings, and take our rest in the shade of his wisdom. But, most importantly, we are spared the fear of making the mistake of not noticing this man’s holiness. We are spared the temptation of straining at the gnats of his small mistakes while swallowing the camel of his unjust condemnation. But all the same, we are not spared the temptation of denying ourselves the delight to be found in reading his works.

His books are on our shelves. Pick up any one of them, and the divine possessor of a heart of gold will begin to speak with you. You will see his golden mouth in front of you; you will see a flame like that of the Burning Bush, which burns without consuming. John will call you to follow him: he will rouse, pester, intimidate, persuade, and inspire you. If you go after him, things will become very difficult for you – as difficult as they should be for all that will live godly in Christ Jesus [2 Timothy 3:12].

But if you and I do not follow him, if we agree to “honor him from a distance,” and do not open his books, such “veneration” will show that if Chrysostom were living today, we would be among those who condemned and exiled him.