In memory of His Holiness, the late Patriarch Maxim of Bulgaria, who reposed on Tuesday in the 99th year of life, we offer a brief biographical sketch, an interview given by His Holiness to Goran Blagoev as part of a documentary film presented by Bulgarian National Television, and a gallery of photographs.

Patriarch Maxim of Bulgaria during Patriarch Kirill’s visit to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. Photo: S. Vlasov, Press Service of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia

Patriarch Maxim (Marin Naydenov Minkov) was born on October 29, 1914, in the village of Oreshak near the city of Troyan, into the family of a craftsman. At the age of twelve he was given by his parents to the Troyan Monastery to be a novice.

From 1929 to 1935 he studied at the Sofia Theological Seminary, from which he graduated. On December 13, 1941, he was tonsured a monk. On July 12, 1947, he was raised to the dignity of archimandrite.

From 1950 to 1955, Archimandrite Maxim was rector of the Bulgarian representative church in Moscow. On October 30, 1960, he was made Metropolitan of Lovech. Following the death of Patriarch Cyril of Bulgaria in 1971, he was enthroned as Patriarch of Bulgaria and Metropolitan of Sofia on July 4, 1971.

Your Holiness, how did your parents influence your decision to become a priest?

My parents were simple villagers. Mother came from a wealthy family, but married a poor young man who had been orphaned in childhood. They lived together in harmony, regularly attending services at the Troyan Monastery. Father was a permanent member of the ecclesiastical rectory in his native village of Oreshak. My mother was the spiritual center of village life, gathering neighbors for prayer and the reading of spiritual literature.

Mother very much wanted me to receive a religious education and become a servant of the Holy Church. I am grateful to my parents for raising me in the faith and in the Church. They supported me with great difficulty during my time in seminary. Tuition was then 8,000 leva a year for board. They had no way to earn that kind of money. Father was a craftsman. He was compelled to become a policeman and, although his duties were in the kitchen, he worked in a uniform. The family did not go hungry, but we lived in poverty.

How did you decide to become a monk?

While a student in one of the upper classes of seminary, I wrote a letter to the Monastery of Zographou on the Holy Mountain asking to be received as a novice following the completion of my studies. I dropped the letter into a box, the contents of which were reviewed by teachers before being mailed.

A few days later, one of the teachers summoned me and asked: “Marin, do you want to become a monk?” I replied: “As God blesses. Perhaps I’ll become a monk.” The teacher said that I could serve the Church as a priest. He convinced me to become a married priest and not to rush into monasticism. Most likely he had intercepted my letter to Zographou.

But my ardor for God and desire to become a monk stayed with me. They were maintained thanks to my fellowship with the brotherhood of the Troyan Monastery, of which I was a spiritual child.

Two Patriarchs. Patriarch Kirill’s visit to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. Photo: S. Vlasov, Press Service of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia

In December 1941, when I was in the fourth year of the Theological Faculty [at Sofia University], I became a monk. Archimandrite Clement (Koevsky), abbot of the Troyan Monastery, was my spiritual mentor [nastavnik], while Metropolitan Paisiy (Ankov) of Vratsa became my spiritual elder [starets].

Monasticism gave me spiritual repose. At my tonsure I was given the name Maxim, in honor of St. Maximus the Confessor. I am happy that I bear the name of a saint who endured persecution and terrible ordeals from the secular authorities while remaining faithful to Holy Orthodox Truth. He is a role model to me, and I always turn to him in prayer for help before the Throne of the Almighty.

You were elected Patriarch in 1971, during the atheist regime. Did you not have difficulties in your high-ranking office?

My election as Patriarch caused me great unrest. In those days it would have been easier to die than to understand and make sense of how to live and how to perform the duties of Primate of the Holy Church. How much unrest I experienced! I reflected on this, taking into consideration the positive attitude of the Synod, the clergy, and the church community towards the possibility of electing me as Patriarch.

This attitude on the part of the city’s church public was especially apparent in the person of the academician Mihail Arnaudov, who helped me to accept the decision to take on a ministry accountable to the Church, the nation, and the Motherland. I knew the academician Arnaudov from the time he served as an official in the Metropolia of Ruse. We gradually became close. On the eve of the election I happened to meet him in the gardens near the Military Club in Sofia. He knew that I had abstained from presenting my candidature. Thanks to his authority, he convinced me not to refuse to take part in the elections.

Photo: www.pravoslavieto.com

And yet you became Patriarch when the communist regime was in power…

It was a difficult situation. The atheistic regime did everything it could to diminish the value of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in the eyes of the people and to destroy faith in the God Whom it confessed.

Once, during Great Thursday services in the Sveti Sedmochislenitsi Church [dedicated to Sts. Cyril and Methodius and five of their disciples] in the capital, I was informed that the government was intending to forbid priests from processing around churches with supplicatory services and ringing bells in commemoration of the establishment of canonical order. I categorically refused to give my consent, regardless of where this initiative had come from. As it turned out, it came from one of the most important officials of the time.

The restrictions against attending services that were in place for everyone – but especially for school kids, young people, and children – weighed especially heavy on me. I did everything possible to overturn these obstacles, especially through the Committee for Church Affairs, which was headed by Mikhail Kyuchukov, who had earlier been my classmate. We were students together in seminary from the first through sixth classes; he sat in front of me.

The atheistic period struck a tremendous blow against the Holy Bulgarian Orthodox Church and its life, but not its confession. The first years of the atheistic regime were very severe. The obdurate attitude of the authorities towards the Church was later mitigated somewhat, but it did not disappear altogether, inasmuch as communist ideology filled people with varying degrees of bitterness and animosity towards the Church.

But the Church’s significance as the most important institution in Bulgaria survived. It was obvious that no one could diminish its significance in the life of the Bulgarian people. If you deny the Church, you also deny Bulgarian history.

With Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev). Photo: mospat.ru

You said that the atheistic regime did not destroy the Church, but that it wanted to weaken it. But I remember that on the May 24 national holidays you were sometimes on the podium of the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum [first communist leader of Bulgaria] with Todor Zhivkov [communist head of state, 1954-1989]. Did the Church not cooperate with the communist regime?

I was, I was… I was next to Todor Zhivkov… (Laughs.) You should understand that there was no cooperation between the Church – and me personally – and the civil authorities at these events. But there were certain joint efforts between the government and the Church in good undertakings, in which the Church played its rightful part.

The Church took part in the struggle for world peace, but to the extent and in such a form that the Church participated precisely as the Church, by preaching its Gospel precepts for attaining peace. This was by no means some sort of service with the civil authorities of that time. I always thought above all about the Church’s interests, even when fulfilling my civic responsibilities. I did not make any compromises. I had many painful experiences because of this, but I endured them all.

My presence on the podium in those years did not come as the consequence of a desire to cooperate with the communist authorities. I was fulfilling my civic duties.

At one of our meetings, Zhivkov demanded of me that local bishops, in addition to fulfilling their ecclesiastical ministry, should also become chairmen of the Fatherland Front [at that time a communist-dominated popular front]. Bishops’ deputies, in turn, were to head local organizations of the Fatherland Front. I answered him that I could not permit this, inasmuch as the Bulgarian Communist Party was atheistic. I could not allow bishops to become chairmen of an organization governed by the Communist Party.

“Well, if that’s the case,” Zhivkov said, “how do you suggest that we unite the people?” I replied: “The Church has always worked for the unity of the people: it advocates it now, and it will advocate it in the future – but by attracting others to itself, not be accepting the principles of an alien ideology.” Such was my conversation with him.

What was your attitude towards Zhivkov? You have been accused of making use of his support.

My first meeting with Todor Zhivkov was ceremonial, in my capacity as the newly elected Patriarch. At that time, the Council of Ministers had decided to destroy completely the Church of the Savior in central Sofia. Before going to see Zhivkov, I told Kyuchukov that I would bring up the question of this church. He tried to dissuade me: he said that the Council of Ministers had already reached its decision.

Nonetheless, after the official conversation with Zhivkov, I began to speak about the church that had been condemned to demolition, about how it was a medieval monument venerated by believers, and about how it needed to be preserved.

He replied: “It is possible that the Council of Ministers has decided this. But if it was reported incorrectly, then the decision to destroy it is also incorrect. This issue will be resolved.” The issue of the church’s preservation was then decided positively. Although, unfortunately, even today this church is in such condition that it cannot be used for holding services.

I had four official meetings with Zhivkov. At one of them I raised the issue of preserving the St. John of Rila Church in Pernik, which they wanted to destroy because they were constructing a building for a Party organization next door. During my final meeting, in 1989, I asked about the return of the Theological Seminary from Cherepish Monastery to Sofia. I never had any personal contact with Zhivkov.

The Lord said that there is no man who is without sin. Does the Bulgarian Patriarch have any sins?

How could I say that I have not sinned, that I have no sins?! Not only does conscience not allow this to be said, but it would even be contrary to the words of Holy Scripture, that there is no man who could live for a single day without sinning. Of course I have sinned, as have all people; but I have never made any compromises to the detriment of the Church, and have never even let myself think of allowing this.

Of course, I have committed occasional sins in assessing what would be best for the Church. But I have always done everything I could for the good of the Church, except for making shameful compromises with anyone at all – and especially with the powers of this world or the authorities. When it was necessary to make a choice, I chose what I thought would be best for the Church, not for myself.

Visit of His Holiness, Patriarch Kirill, to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. Moleben in the Synodal Chapel. His Holiness greeting Patriarch Maxim of Bulgaria. Photo: S. Vlasov, Press Service of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia

Other photographs

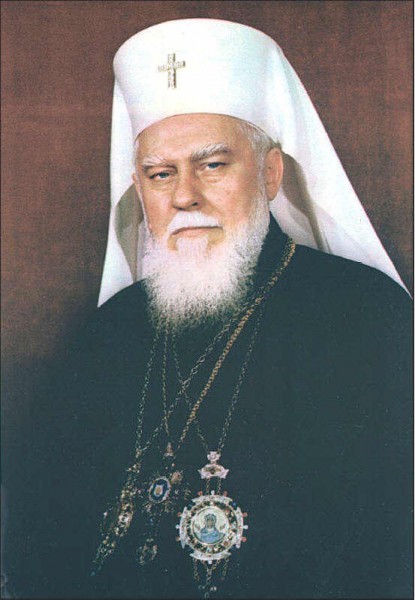

His Holiness, Patriarch Maxim of Bulgaria

Celebration of the Nativity of Christ, St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia

Divine Liturgy in the St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia

His Holiness, Patriarch Maxim of Bulgaria

Meeting of Patriarch Maxim with President Putin

Paschal service, 2012

His Holiness, Patriarch Maxim with President Rosen Plevneliev of Bulgaria

Translated from the Russian