Question:Greetings! Lately I’ve been tormented by the questions: “What is the meaning of life?” and “What do we live for?” My thoughts won’t leave me alone: I’m constantly thinking about these questions, I’m like a mass of contradictions. Please answer my questions! Thanking you in advance, Liudmilla, age 19.

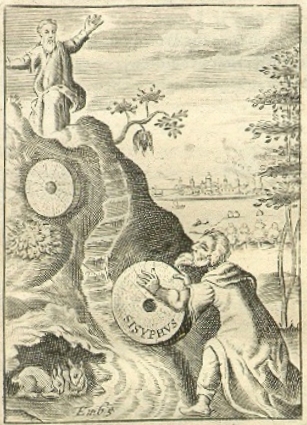

Answer by Hieromonk Job (Gumerov): Man has given thought to the meaning and purpose of life since antiquity. The Greeks had the myth of Sisyphus, king of Ephyra (Corinth). As punishment for his deceitfulness, in the underworld he had to roll an enormous rock up a mountain for eternity. But as soon as he reached the peak, an invisible force propelled the rock back down to the bottom – and then the same pointless labor began all over again. This is a striking illustration of the meaninglessness of life.

In the twentieth century, the writer and philosopher Albert Camus applied this image to modern man, judging the central feature of his existence to be absurdity: “At that subtle moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning toward his rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated actions which become his fate, created by him, combined under his memory’s eye and soon sealed by his death. Thus, convinced of the wholly human origin of all that is human, a blind man eager to see who knows that the night has no end, he is still on the go. The rock is still rolling.” [1]

The conclusion at which Camus arrived was inevitable both for him and for the millions of others who have lived, and are living, in unbelief. The only difference is that Camus tried to be logical to the very end; he was able to recognize acutely that man’s life, when confined to the framework of earthly existence, resembles the labor of Sisyphus. However, the majority of people try to live in illusion and to find meaning in this earthly life. But in a world of finite realities, meaning is impossible to find.

Mathematicians know that any finite number, divided by infinity, is infinitesimal: that is, its limit is zero. That is why attempts by non-believers to explain the meaning of life are so naïve. Some assert that they value life with its accompanying joys, and are quite satisfied therein. But earthly life dries up, like water into sand, with none of the joys remaining. And if all this disappears within a few decades, does such a life have any meaning? Others say that they see their purpose in leaving something behind through their actions. One normally hears such explanations from people who are not engaged in serious creative pursuits and who do not leave anything real behind. However dedicated to their work the most outstanding creative minds of both the past and the present may have been, they understood well the incomplete and limited nature of such activity.

The great mathematician and physicist, Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), two years before his death wrote to the mathematician Pierre de Fermat that he saw mathematics as nothing more than a craft. The real purpose of human existence, in his opinion, could be revealed only by true religion: “In order to make man happy, it must prove to him that there is a God; that we ought to love Him; that our true happiness is to be in Him, and our sole evil to be separated from Him; it must recognise that we are full of darkness which hinders us from knowing and loving Him; and that thus, as our duties compel us to love God, and our lusts turn us away from Him, we are full of unrighteousness. It must give us an explanation of our opposition to God and to our own good. It must teach us the remedies for these infirmities, and the means of obtaining these remedies. Let us therefore examine all the religions of the world, and see if there be any other than the Christian which is sufficient for this purpose.” [2]

In our age everything remains the same. People with a healthy moral sense, who have achieved even the most outstanding results in their creative activity, cannot accept this as the main goal of their lives. I will give an example. The academician Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (1906-1966), being the general director of our space program, could not be satisfied with this; he thought about salvation, that is, he saw the meaning of his life as being beyond the boundaries of earthly life. In those years, when faith was persecuted, he found the opportunity to have a spiritual father, to travel to the Pühtitsa Convent of the Dormition [in Estonia], and to engage in generous acts of philanthropy. Nun Silouana (Nadezhda Andreevna Soboleva) has preserved stories about this remarkable man:

“In those years I was in charge of the guesthouse. Once a stately man in a leather jacket came to visit us. I gave him a room. I spoke to him kindly and brought him something to eat: the same old potatoes with mushroom sauce. He spent two days with us, and I saw that he was becoming more and more bewildered. Finally, we had a proper conversation. He said that he did not at all expect to find such poverty, even destitution here… ‘I very much want to help your convent. It breaks my heart to see how you live. I have very little money on me just now, and it was only by a kind of miracle that I could escape here. I need to go back to work and don’t know if I can visit you again soon.’ He left his address and telephone number with me, saying that when in Moscow I should be sure to visit him. I thanked him and gave him the address of a poor priest who lived with his wife on 250 rubles a month (on the old currency), saying that he should help him if he can.

“A month later I am given leave by blessing of the abbess to go to Moscow. I arrived and located the address he had given me. I see a huge fence with a gatekeeper, who asks me: ‘Who are you here for?’ I give his name. He lets me through, saying: ‘You’re being expected.’ I go on, becoming more and more amazed. In the depths of the courtyard is a mansion. I ring the bell and the door is opened by the owner: the very same man who had visited us. How delighted he was! He takes me upstairs, to the second floor. I enter his study and see a volume of the Philokalia lying on his desk and a cabinet in the corner, with open panels, behind which stands an icon. He invites a woman (his sister, I think) to get everything ready. In the sister’s room is a kiot made of walnut with a wonderful icon if St. Nicholas.

“Before my departure he hands me an envelope, saying: ‘Here is five.’ I thought he meant 500 rubles – but it turned out to be 5,000 rubles. How helpful that was for us! A long time passed, and then my friend came to visit again – it was the academician Korolev – and we sat in my cell drinking tea. He thanked me: ‘You know, thanks to you I found a true friend and pastor: that poor priest about whom you spoke.” [3]

I related this story in detail to show that Korolev’s conversion to Orthodoxy was not just a passing episode in his life. He lived in Orthodoxy and risked his high status for the sake of meeting his spiritual needs. With all his enormous responsibilities as director of the space program, he still found time for reading the Philokalia, a profoundly ascetic work of the Holy Fathers.

Not only science, but even artistic creativity cannot constitute the meaning of human life. Pushkin, already gaining renown as the premier Russian poet, wrote “Three Springs” in 1827, a poem expressing an agonizing feeling of spiritual thirst [4]:

In this world’s wasteland, borderless and bitter,

Three springs have broken forth with secret force:

The spring of youth, abubble and aglitter,

Wells up and runs its swift and murmurous course.

Castalia’s spring of flow divine is letting

In this world’s wasteland exiles drink their fill.

The last, cool spring, the spring of all-forgetting,

Will slake the burning heart more sweetly still.

The soul of the twenty-eight-year-old poet did not find complete satisfaction in the pleasures of a life that “Wells up and runs its swift and murmurous course.” The Castalian Spring (near Delphi on Mount Parnassus in Greece) is a symbol of poetic and musical inspiration. Water from this source likewise cannot quench a thirsty soul. For the poet, who was then only beginning to grasp the vital significance and spiritual beauty of Christianity, the sweetest water of all came from the cool spring of forgetting afflictions, sorrows, and worldly vanity and care. Several months before his death, Pushkin wrote: “There is a book every word of which has been interpreted, explained, preached on, in all the corners of the earth, applied to every possible human situation and world event, from which one cannot repeat a single expression which would not be known by heart by all men, which would not already be a popular saying, which contains nothing still unknown to us; but it is called the Gospels – and such is its perennially renewed delight that if we, being satiated by the world or cast down with melancholy, chance to open it, we have no power to combat its sweet fascination and we steep our spirits in its divine eloquence” [5]

We have reached the answer to the question you posed. The teaching on the meaning of life is to be found in the Holy Gospel. The word of God reveals to us the truth that life is more precious than food (Matthew 6:25) and that saving it is more important than observing the Sabbath (Mark 3:4). The Son of God possesses Life from eternity (John 1:4). Jesus Christ, Who died for us and rose again, is the Prince of Life (Acts 3:15). The only life that has real (not illusory) meaning is one that leads us into God’s eternity and unites us with Him, the only Source of endless joy, light, and blessed repose. I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in Me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: And whosoever liveth and believeth in Me shall never die (John 11:25). We begin to enter this life while still on earth. The Church, as God’s creation, is the prototype and foundation of eternal life. This new life becomes real here on earth through faith in Him Who is the way, the truth, and the life (John 14:6). The lives of saints give evidence of this. But even someone who has not risen to the level of holiness, but simply follows his spiritual path honestly and responsibly, gradually attains inner peace and knowledge of the meaning of his life.

Dear Liudmilla! You need to enter the millennium-old tradition of Christian life. You need not only to believe in Christ, but to trust Him in all things. Then doubt will be gone and the tormenting questions of your purpose in life will begin to resolve themselves.

Translator’s notes:

[1] Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, Justin O’Brien, tr. (New York, NY: Vintage International, 1955).

[2] Blaise Pascal, Pensées, W. F. Trotter, tr. (New York, NY: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1958).

[3] Tri vstrechi [Three Encounters] (Moscow, 1997).

[4] Alexander Pushkin, Collected Narrative and Lyrical Poetry, Walter Arndt, tr. (Ardis Publishing, U.S., 1981).

[5] Tatiana Wolff, Pushkin on Literature (London: The Athlone Press, 1986).

Translated from the Russian