The British Government has supported the right of an employer to dismiss an employee for openly wearing a cross in her workplace. Moreover, it is sticking to this position in two other cases which have been taken to court by Christians who are defending their right to wear a cross.

Below, Olga Sedakova, poet, writer, philologist, ethnographer and the holder of a Ph D in theology from the European University of the Humanities, reflects on the battles for the cross.

The fight to wear a cross inBritainis merely an episode in a whole battlefield of cases concerning ‘religious symbolism’ in the ‘post-Christian’ world. I am a direct witness to another episode in the struggle.

Two years ago the Council of Europe demanded that crucifixes be removed from State schools inItaly. Schoolchildren and teachers alike didn’t allow this to happen. They took the protest to the streets. The argument behind the European decision was that it defended those whom such a symbol might offend – Non-Christians or simply atheists.

Among others, schoolchildren held up posters saying ‘The majority have their rights too!’. It was not that all these Italian children and teachers were zealous believers: for many of them (perhaps for most of them) the decision was simply a mockery of an ancient tradition. And they were not allowing it.

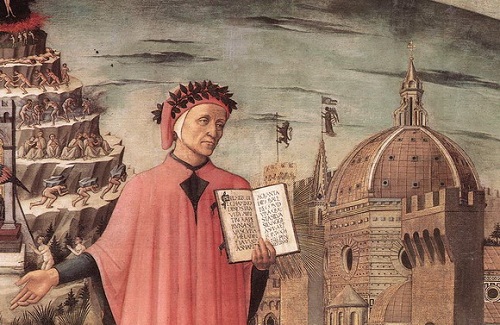

Yesterday I read in «Corriere della Sera» of the outbreak of another battle in this great war: The Commission of European Experts, headed by an Italian Valentina Sereni, has been examining Dante from a legal perspective and concluded that his ‘Divine Comedy’ must be banned from school curricula because it contains ‘elements of racism’, for which criminal liability has now been established. At the very least the text must be censored.

I have studied Dante for many years and was so struck by this diagnosis (racism!) that I read the article to the end.

The Divine Comedy has once before been prohibited reading, but for a different reason. This was because Dante spoke of a number of popes of his age and the right of the pontiffs to wield secular power in such a way that it could only be termed heresy. Dante was one of the first to defend the concept of ‘the division of powers’ into spiritual and secular, in other words, he was one of the fathers of secularism.

This idea, which was implemented in Europe only much later, after the Enlightenment, presupposed that social life is regulated not by theocratic laws, but by universal laws of reason and morality which are presumed to be the same for all people and are contained in human nature itself.

The accusation of heresy was long ago dropped from the Divine Comedy. The papal coat of arms contains two keys – one representing secular power, the other spiritual power – but nobody for a long time has mentioned the secular power of the Church. John Paul II was a personal patron of the Dante Society. Today’s demand to prohibit Dante comes precisely from secularism, at least the form which it has taken today.

So Dante stands accused of anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and homophobia.

The first accusation is based on his portrayals of Judas (!), Caiaphas, the high priest Anna, the Sanhedrin and the Pharisees. But Dante invented nothing here; he simply followed the New Testament story. However, that does not redeem him, because the Gospels themselves have been shown to be ‘sources of anti-Semitism’.

His Islamophobia is shown by his portrayal of Mohammed who is imprisoned in hell with the creators of schism, suffering terrible and humiliating torments.

There are also homosexuals in Dante’s inferno. These he calls sodomites and terms their sin as ‘sin against nature’. Dante meets his old friend Brunetto Latini there. Conclusion: homophobia.

Do interpretations of this sort not remind us of the Soviet period, when all works of art from all over world were interpreted from the viewpoint of ‘the class struggle’ and there were debates about, say, Pindar or Shakespeare? (By the way Shakespeare is now also suspected of anti-Semitism for his ‘Merchant of Venice’).

But there is a difference. Communist doctrine was never, in any way, a form of secularism, as many of us think. We never had secularism. The Soviet system was an ‘ideocracy’, that is, a quasi- or para-religion.

It was not the universal, ‘neutral’ reason recognised as a criterion in Soviet Russia but ’the all-conquering teaching’. Only ‘faith’ and ‘a total loyalty to the Party’ was demanded of loyal citizens. They were also required to be ‘militant atheists’. This was the world of national rituals (often copied from Church rituals and reinterpreted) and ‘shrines’: the portraits of leaders played the role of icons, without which it was unthinkable to leave any official premises unadorned. This para-religion had its own ‘martyrs’ and ‘prophets’. Here there was no secularism, that is, no space for the reason devoid of any mythology

Now such ‘shrines’ and icons’ are being defined as ‘neo-pagan’. Then they were considered to be just ‘neo’, very, very ‘neo’. An ideocracy is a special spiritual education, a ‘transformed’ religiosity. In it, pagan symbols are also at the disposition of very different ideas, different idols, untrusted by morality or reason.

Communist doctrine worked through a ‘majority’ – any minority was viewed as something to be eradicated. Secularism – our starting point – defends minorities and calls on the majority to give way to those against whom it traditionally discriminated.

However, as a result, it turns out that Dante is unacceptable to both secularism and Communism. The Communists tried to censor him in their own way – they liked his hellish Inferno, but his ‘Paradise’ was another matter.

I think that when we hear of events like ‘the Dante affair’, or the removal of crucifixes or the prohibition to wear a cross, we can say that secularism is becoming a new ideology, that is, a new para-religion, which categorically rejects the use of the reason.

Reason alone should have been enough for the experts to understand that Dante, ‘a 13th century Christian’, as he called himself, could not relate to other religions in any other way. And that much later concepts of ‘anti-Semitism’ and ‘Islamophobia’ are not relevant here. And that Dante could not doubt in the Church’s and the Bible’s teaching about sin.

An ideology – unlike secularism, as it was originally conceived – puts forward certain eternal positions, true for all people and for all time. It cannot help distorting the facts so that they fit its interpretation. It has to hush up or falsify reality, both contemporary and historical. We are now witnessing the tranformation of secularism into ideology, and that, as we know, will only leave burned earth behind.

Moreover, the most important characteristic of ideologies is that they do not in any way respect humanity, they all want to decide every detail for us. Paradoxically, secularism, which defends human dignity and freedom of conscience, now looks at human beings as those who will read about the torments of Mohammed in Dante’s ‘Inferno’ and at once become Islamophobes. You must not imagine that someone will think about what he has read and draw his own conclusions. You must simply censor the dangerous part.

And here is another conclusion from ‘the Dante affair’ (after which may well follow ‘the Shakespeare Affair’ of ‘the Pushkin Affair’): We can see just to what extent the European (and Russian) classics were fundamentally Christian. Another classics we do not have. Thus, in order not to offend anyone, we have to stay completely empty.

Translated from the Russian