Several days ago, my wife and I fell into one of those silly little squabbles that are such a prominent feature of day-to-day married life. You know the kind of fight I am talking about: they are never about the meaning of life, the existence of God, or even the profound ethical implications of cloning. The most fights are rather about those other big issues: whether or not the toilet seat should be left up; whose dirty dishes those are; where the salt shaker should be kept. You get the point.

Several days ago, my wife and I fell into one of those silly little squabbles that are such a prominent feature of day-to-day married life. You know the kind of fight I am talking about: they are never about the meaning of life, the existence of God, or even the profound ethical implications of cloning. The most fights are rather about those other big issues: whether or not the toilet seat should be left up; whose dirty dishes those are; where the salt shaker should be kept. You get the point.

These petty quarrels unleash what I consider the deadliest poison in any human relationship: resentment. Take my recent conflict, for instance. Something was left out and not returned to where it belonged. I reacted by delivering a little lecture, which my wife did not receive well. We had words, and I went upstairs. A short while later, I apologized ungraciously. The apology was accepted, but not reciprocated.

That, for me least, was the lance that pierced the boil. I had condescended to show some remorse for something that I truly believed wasn’t really my fault. How dare she not apologize in return? I said nothing at the time, but the demon was out. I smouldered with resentment for the rest of the day. I felt depressed, heavy and irritable about everything. Life suddenly became bitter and grey—and all over an item out of place!

This is resentment: the conscious act of nursing a grudge against a fellow human being for a real or imagined wrong they have committed against us. Someone fails to live up to our expectations, gets in our way, interrupts our plans, won’t follow our agenda or meet our deadlines. And when we correct, these persons compound their wrongs by refusing to straighten up and fly right. They may, if they are very accommodating, try to toe the line for a while, but inevitably they fail to become the people we would like them to be.

The result: we resent them. We sulk. We brood. We analyze them endlessly and fruitlessly. We work ourselves up and get frustrated. And all our frustration, our failure to correct the other person’s supposed wrongs lead us to become more angry, more resentful and more miserable within ourselves. Meanwhile the object of our resentment goes on with their life. They may recover from the spat and even interact with us as if it never happened. They begin to act as if this really wasn’t the end of the world…

How dare they!

Spiritually speaking, resentment is our reaction to discovering that we cannot control the personalities and actions of others. In short, we are not God. When people around us fail to submit and act on cue, according to our directions, the limits of our power over them is exposed and we lash out like a thwarted petty tyrant throwing a tantrum. As this “inner Napoleon,” kicks and screams, he may hurt others, but his ultimate victim is the soul that he inhabits, namely, our own. That’s why resentment so often leaves us feeling far worse than the person against whom our resentment is directed. As someone once said, “Resentment is the poison we drink, hoping someone else will die.”

Petty and imagined grievances notwithstanding, people often act in ways that really cross our boundaries, offend, injure or even abuse us. When such actions reveal our lack of godlike power, however, we are the ones who decide to react by throwing the inner paroxysm that wreaks so much spiritual and emotional havoc in our hearts and minds. Suffering is a reality for any created being. Because we are limited, we are subject to the forces beyond our control. However, resentment of our suffering is a choice we make, the futile fist-shaking of one who would be God and won’t accept his humanity.

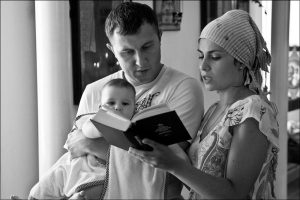

If resentment is a spiritual ailment, rooted in the failure of our godlike ambitions, then the cure must also be spiritual. I am not talking merely about more religious activity: prayer, Bible reading, church attendance—good and beneficial as these are. I am talking about concrete action. When others do things to expose our human limitations, we must face the revelation without seeking to escape from them through fantasy, analysis, entertainment, spending, etc. Next we must surrender our struggles to a Power greater than oneself: not just God in the abstract, but God as He makes Himself known in people who are objective, who love us, and who are not afraid to tell us the truth about ourselves. Only then can the abscess of our prideful egos be lanced and drained, and true healing begin.

The end result of this healing is the exact opposite of resentment: acceptance. God is God, and I am simply a member of the human race. To quote from page 449 of the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous: “Acceptance is the answer to all my problems today. When I am disturbed, it is because I find some person, place, thing or situation—some fact of my life—unacceptable to me, and I can find no serenity until I accept that person, place, thing or situation as being exactly the way it is supposed to be at this moment. Nothing, absolutely nothing happens in God’s world by mistake… Unless I accept life completely on life’s terms, I cannot be happy. I need to concentrate not so much on what needs to be changed in the world as on what needs to be changed in me and in my attitudes.”

Reprinted with the permission of the author. If you wish to reprint the article, Fr. Richard’s permission is required.