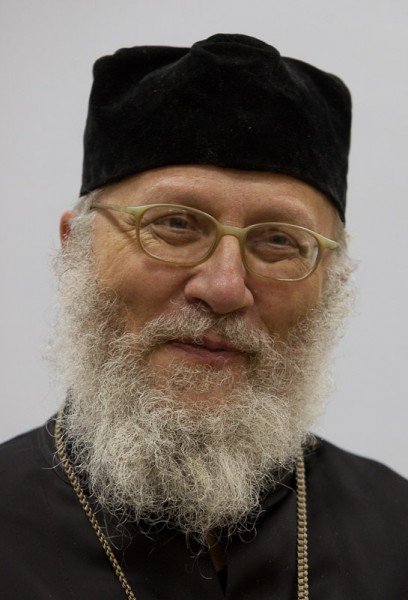

On the feast of the Epiphany in the cycle of conversations “Man before God”, bishop of the Orthodox Church in America His Grace Seraphim (Sigrist) visited the Christian club “The Meeting” with a lecture on “Orthodoxy in America. The Сhurch as a community”, and answered questions from the audience.

On the feast of the Epiphany in the cycle of conversations “Man before God”, bishop of the Orthodox Church in America His Grace Seraphim (Sigrist) visited the Christian club “The Meeting” with a lecture on “Orthodoxy in America. The Сhurch as a community”, and answered questions from the audience.

Three principles of Orthodoxy in the West

His Grace began his lecture with memories of the Rev. Alexander Schmemann, who taught at the seminary while Vladyka studied there. Fr. Alexander began his course of lectures on church history by showing how everything connected in history so that Christianity could be understood and accepted in the world: the Old Testament, “the existence of the Roman Empire, which allowed the Christian message to spread throughout the world”, and pagan religion with its dying and resurrecting gods.

He said that the main objective of his course was to turn us into Christians. His teaching was not a purely academic experience. He wanted to actually touch and change lives. Perhaps therein lays the difference between living theology and academic theology.

Now much is happening in the world that makes, constitutes a type of model of Divine Providence. So I’d like to think of Orthodoxy in the West. I want to consider how God is working today in the East and in the West. Thinking about this can help us become Christians, and once again realize that God is alive!

Speaking of Orthodoxy in the West, Vladyka designated three points:

— Multi-ethnicity,

— The importance of the laity along with the clergy,

— And the relevance of the question, what is Orthodoxy.

On the principle of multi-ethnicity Bishop Seraphim brought as an example the American Orthodox Church. The bishop briefly outlined the main points of its history, emphasizing the missionary nature of the Church in America: it nourished the large un-Russian Diasporas, and the tribes of Alaska, the Syrians, the Carpatho-Russians…

Initially, the Orthodox Church in America consisted of many different nationalities. In America, you are not Orthodox “because you’re Russian”, “because you’re Greek”, “because you’re Syrian”. You are just Orthodox. So in America, the Church reveals itself not as a Church of one nation.

Archbishop Seraphim noted several reasons for the active participation of the laity in the life of the American Church.

One reason is the historical tradition of laity brotherhoods coming from Eastern Europe: Poland, Ukraine. Sometimes during conflicts between the Eastern Rite Catholics and the Orthodox, the question of church ownership would arise, and the priest could choose one or the other, but the laity brotherhood kept the faith. This tradition came to the American Church through the Carpatho-Russians.

I also think that the American tradition of democracy has affected the Church. There is a feeling that the people should be involved in making every decision. A similar situation exists in many Western churches, but in the Orthodox Church in America synods involve lay people, priests, and bishops. In the election of a metropolitan the laity participates equally with the clergy.

There was also active participation of the laity in the diocese headed by Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) and Archbishop Gabriel of Paris…

In practice, of course, it is important not so much what people do during synods, but rather what they do to participate in the daily life of the Church. I remember when creating a new parish in Princeton (New Jersey), three concepts had to be followed:

1. Missionary work must be a matter of not only the priest, but the entire community.

2. The community should engage in social activities, help the poor …

3. The community should be missionary and ecumenical.

Most important, in my opinion, is the concept that missionary work should be for all, not only for the priest.

The third point: the presence of Orthodox Church in the West puts people in the face of the question: “What is Orthodoxy?” Sometimes people say that Diasporas of Orthodox nationality around the world are necessary, because it allows the Orthodox Church to be missionary. Maybe it is so, but the question arises—what can we offer people?

I remember that when a parish in Pennsylvania switched from the Old to the New calendar, their warden said: “Since we now celebrate Christmas on December 25th, we are as Catholics!” This situation shows that if you ask the people what it means to be Orthodox, this question is not so simple. In Russia, it seems simpler: I am Russian, so therefore I am a part of the Russian Church. In Greece, I am Greek, and so I’m in the Greek Church. In Western countries this does not work, you need to understand why exactly you are Orthodox.

Is Orthodoxy an escape from reality or simply Christianity?

Here you can go in several directions. We can say that Orthodoxy is a form of rejection of the modern world. Someone becomes Orthodox to escape from the problems of the modern world. This type of Orthodoxy builds a wall that protects us from the world. A friend of Father Seraphim (Rose), Father Herman Podmoshensky remembered how he once stood in some American city, and thought: “This is a horrible society! I don’t want to understand anything in it!” Then it dawned him: “I am not American! I am Russian!” This moment for him was very important.

I do not think that feeling Russian is the solution to all problems. But one of the ways in which Orthodoxy can go is to be on the defensive side, though of course we want something else-genuine Orthodox Christianity.

The situation in the West forces us to address this issue.

As mother Maria (Skobtsova) wrote in her book “Types of Religious Lives”, we have the opportunity to receive Christianity as a religion that is aesthetic, ascetic, supports the institution of the Church, and feels the value of Christian history. But ultimately, it is not Christianity of the Bible. It remains a type of evangelical Christianity, which showed the life of mother Maria (Skobtsova).

Orthodoxy can be that evangelical Christianity. Throughout history, Orthodoxy experienced all types of temptations: the temptation of aesthetics, the ascetic temptation, the temptation of delight in its history. Yet in the end it can come back to the Gospel and become the Church of the Gospel. This is what C.S. Lewis wrote about in his book “Mere Christianity”.

This is also consistent with the idea of Fr. Nicholas Afanasiev, who noted that the Church is a gathering of people for the separation of Bread and Wine.

There is the human temptation, that if a Church is here, there, and in many other places, then that Church should be most important and control the rest. In the opinion of Afanasiev, wherever there is the Eucharist, wherever there is a breaking of Bread, there is revealed the whole Church. This is the mathematics of the Church: 1 +1 = 1. Each has completeness.

I think that Afanasiev’s idea comes from experience of the Church in the west. His idea is not the only one in the question about what is the Church, but we see that this is an example of creative thinking about the future of the Church.

Community in the Church and in the world

This brings us to the question of community. The fact of multi-ethnicity also leads to this question. How can different people be together? How do people who do not share the same values, us and those that do not belong to the Church – how can we be a society? Father Alexander Men said: “How can we, who are so different, share one planet?” (“Monsignor Quixote”, a dialogue between a Christian and a Marxist). But the world’s history, the nature of things and God’s Providence tell us that we must learn to live together and be a community.

Part of the picture is that all people must learn to live in a community. A lesser problem: Russian and Greeks must learn to live together in one Church.

This phrase was uttered with irony and brought a smile to the audience. His Grace emphasized that the question “What is church?” thus becomes relevant to the whole world.

In fact, today there is no more “Eastern” or “Western” – in this age of globalization, if you are Russian or if you’re an American, you live in the same wonderful, holistic world.

At the end of the lecture, Bishop Seraphim once again outlined the key questions: What is the Church? Who is responsible for missionary work? How to be a witness of the resurrected Christ in the world?

After that, he answered the audience’s questions.

Excess of freedom?

The first question was if the Church of America is growing, to which His Grace replied that it is difficult to calculate all of the Orthodox: some come, some leave, but everything depends on the community. Active communities are growing, yet there are parishes with only few remaining elderly people, and these parishes will disappear in about 20-30 years.

The next question was devoted to the “freedom excess”: if it is widespread in America that often the priest has to obey the caprices of the parish by entertaining the parish with picnics just to be with them.

His Grace at first did not understand the question: “What does the priest want to do instead?” he asked. “I’m trying to imagine what it means to have excess of freedom…”

In reply to the explanation that at best, an excess of freedom can result in picnics, and at worst carnivals and Disneyland, the guest laughed and said:

-If this is the worst, then it’s not bad.

The main question is that of our faith, whether or not we are doing everything for the glory of God. It is not so bad to get together for a picnic, you can pray together, sing. Christians should enjoy socializing with each other not only in church, but also on other days.

If the priest feels that he is forced to behave abnormally, he just needs to discuss this with his parishioners.

This is reminiscent of why were often criticized representatives of the Parisian school of Theology: Bulgakov, Berdyaev, Zenkovsky, and mother Maria (Skobtsova) – “Theology with a Cigarette”. They could talk about God while smoking a cigarette. This, of course, shows much sensitivity, but it is rather important what they say while smoking a cigarette. If they are saying something good, then we should listen. When Metropolitan Anthony first saw mother Maria, he was shocked because he saw a Russian nun in a Parisian cafe, sipping beer with someone. He felt that this is impossible! But Metropolitan Anthony later came to the realization she wonderfully served God.

Of course, there are many temptations in the world and the Church can lose itself in the world. But it depends on whether we or not we are doing everything for the glory of God.

About humility and pride

In order to become true Christians, we need to get away from counting who has more power. Who has the power, or who does not, who is respected, or who is not. There is nothing good in the feeling of one’s self-importance.

A priest says: “Look, I’m a priest, I spent three years studying in seminary, listen to me! I’m important; do not dare to argue with me!” Father Alexander Schmemann said that some go to the seminary to hide behind the iconostasis, “I am already saved, I won’t be found here!” This is a pathological extreme.

A worldly man says: “I am very important! I own a bank! I donated the most money to this church, and now it belongs to me!”

Or, for example, a university professor: “I am the smartest in the parish!”

But such is human nature. This is natural – the desire to be important. Humility does not come easily.

Missionary work distracts you from yourself. When we help another, it does not matter which one of us is more important- it most important to help that person. This is the meaning of missionary work in the Church.

On Catechesis

There is no one general system. During catechesis it should be understood what is necessary for that specific person, how spiritually deep he has entered the Church, how much he needs to learn. For example, Metropolitan Eulogius, the catechist of Catholic priest Lev Gilet, gave him priestly vestments, and they served liturgy together- such was his catechism. Yet someone else may need to learn a lot.

Many priests baptize people before Easter. Often the catechumenate is a whole year long or a few months before baptism. Taking people into the Church before Easter is the more ancient tradition, but we also baptize at other times.

Russia

Of course, you know Dostoevsky’s novel “The Brothers Karamazov”. When I read it the first time, I was struck by moment when brothers Ivan and Alyosha are in a restaurant. One of them asks: “What shall we talk about?” The second responds: “What Russians usually talk about- God or socialism, which is the same thing, just turned around”.

I think attractive in Russians (and not only) is the desire for the Absolute. The French writer Leon Bloy called himself a “pilgrim of the Absolute”. If we talk about the Russian soul, it is filled with searching for the Absolute.

So there’s the answer to the question what attracts me in Russia- this dialogue from “The Brothers Karamazov”.

Being Orthodox

The audience asked His Grace to clarify: from his point of view, what does it mean to be Orthodox in the West?

His Grace thought for a moment and replied:

– Orthodoxy is just Christianity. And also (why I mentioned Afanasiev) the separation of Bread and Wine. This is the beginning of the Church. I think that theology comes from experience and prayer. The law of prayer is the law of faith. Everything comes from the Eucharist – not as a ritual, but as Communion of Christ, who gave Himself to the world.

Orthodoxy looks complicated because of its lush rituals, but I think it is possible to see the heart of the Orthodox Church, which is simply the union of Bread and Wine. From this stems the life of the saints and our whole tradition. Saint Sergius of Radonezh, St. Seraphim of Sarov, mother Maria (Skobtsova) – their sanctity derives from the Eucharist.

This is only one possible answer to this big question. And this is a question of our time and the question for each of us.

You know the story of Motovilov and St. Seraphim of Sarov. Motovilov asked Father Seraphim why we fast, pray, go to church services. And Saint Seraphim replied: “For acquiring the Holy Spirit”.

In some ways, this dialogue represents the main question of our time. People ask: What is Christianity?

Unlike the rest

One of the last questions asked was if is hard to feel yourself a minority.

-I do not feel that this is a problem. It’s not like, “Look, I have everything, and you have nothing”. We are one society and being an Orthodox Christian, I can share what I have, and the others also bring their gifts.

The problem of any society – Russian or American – is that empty questions are asked. If you watch television, and listen to what questions are discussed, you will understand that these are not the real issues of human life. As I flew from America to Russia, I saw three American films. It was like another planet. They had nothing from real life. I was wondering: who are these beautiful, well-dressed, smiling men and women? Where do they live? I’ve never seen them before.

Then I watched television in Russia and saw the same thing. It’s not Dostoevsky.

The Church is also not Dostoevsky, and not all are required to read Dostoevsky. The Church at all times has said that there is something more in ordinary life. Do not be like those dreamy people from television. Just be yourselves with Christ.

As for the life of the Christian minority, there are ways to suppress it. If a Christian lives in Mecca, his life will be difficult and probably short. But if no one around me knows what the liturgy of St. John Chrysostom is, it’s not a disaster.

Every person who lives around me is created by God, and God loves everyone. And the question is in what I can share with these people I encounter during my life.

My faith depends on God. In the end, you can only rely on God. Everything that is smaller than Him will eventually disappoint you.

If we try to put the Church in the place of God, this will not work, because the Church does not exist for this. If we just believe in God and trust God, then we can learn to love the Church. This is what Father Sergii Bulgakov talked about, he felt at home in the Church, with all that was and with all those who where; not in the context of Church history (which can also sometimes disappoint you), but because his faith was absolutely apocalyptic, waiting for Christ at any moment.

Perhaps this is a very broad answer. But the fear to remain in the minority is a consequence of the fact that God is secondary for you.

Translated from Russian by Sophia Moshura.

Edited by Isaac (Gerald) Herrin.