What shall we offer you, O Christ, who for our sake has appeared on earth as man? Every creature made by you offers you thanks. The angels offer you a hymn; the heavens a star; the Magi, gifts; the shepherds, their wonder; the earth, its cave; the wilderness, the manger; and we offer you a virgin mother. (Nativity Vespers)

In a culture in which a sense of the presence of God is increasingly rare, many people see Christ as a long-dead, myth-shrouded teacher who lives on only in fading memory. There are scholars busily at work trying to find out which words attributed to Jesus in the New Testament were actually said by him. Yet even skeptics celebrate Christmas, at least in a limited way. The problem of miracles doesn’t intrude, for what could be more usual than birth? If Jesus lived, he was born, and so with little or no faith in the rest of Christian doctrine we can celebrate his birth whatever our degree of faith. Pascha is more and more lost to us but at least some of the joy of Christmas remains. Perhaps in the end this feast will lead us back to faith in all its richness. We will be rescued by Christmas.

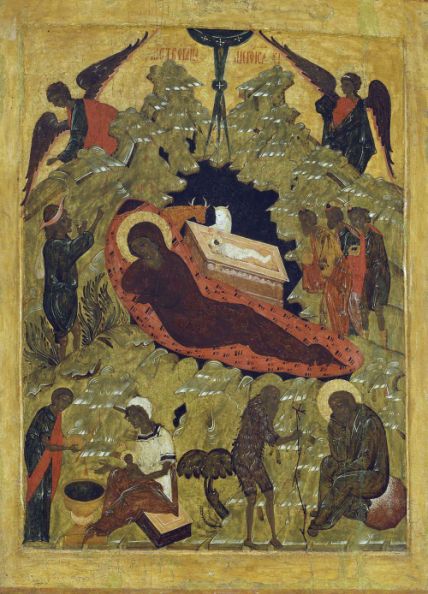

The traditional icon of the Nativity, ancient though it is, takes note of our “modern” problem. There on the lower right we find a despondent Joseph listening to a figure who represents what we might call “the voice of unenlightened reason.” As icons are so deeply silent, we are free to wonder about Joseph’s morose condition. One explanation is that he cannot quite believe what he has experienced. Divine activity intrudes into our lives in such a mundane, physical way. A woman gives birth to a child as women have been doing since Eve. Joseph has witnessed that birth and there is nothing different about it, unless it be that it occurred in abject circumstances, in a cave in which animals are kept in cold weather. Joseph has had his dreams, he has heard angelic voices, he has been reassured in a variety of ways that the child born of Mary is none other than the Awaited One, the Anointed, God’s Son. But still belief comes hard. The labor of giving birth is arduous, as we see in Mary’s reclining figure — and so is the labor to believe. Mary has completed this stage of her struggle, but Joseph still grapples with his.

The theme is not only in Joseph’s face. The rigorous black of the cave of Christ’s birth in the center of the icon represents all human disbelief, all fear, all hopelessness. In the midst of a starless night in the cave of our despair, Christ, “the Sun of Truth,” enters history having been clothed in flesh in Mary’s body. It is just as the Evangelist John said in the beginning of his Gospel: “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness cannot overcome it.”

The Nativity icon is in sharp contrast to the sentimental imagery we are used to in western Christmas art. In the icon there is no charming Bethlehem bathed in the light of the nativity star but only a rugged mountain with a few plants. The austere mountain suggests a hard, unwelcoming world in which survival is a real battle — the world since our expulsion from Paradise.

The most prominent figure in the icon is Mary, framed by the red blanket she is resting on — the color of life, the color of blood. Orthodox Christians call her the Theotokos: God-bearer or Mother of God. Her quiet but wholehearted assent to the invitation brought to her by the Archangel Gabriel has led her to Bethlehem, making a cave at the edge of a peasant village the center of the universe. He who was distant has come near, first filling her body, now visible in the flesh.

As is usual in iconography, the main event is moved to the foreground, free of its surroundings. So the cave is placed behind rather than around Mary and her child.

The birth occurs in a cave that was being used as a stable. In fact the cave still exists in Bethlehem. Countless pilgrims have prayed there over the centuries. It no longer looks like a cave. In the fourth century, at the Emperor Constantine’s order, it was made into a chapel. At the same time, above the cave, a basilica was built.

We see in the icon that Christ’s birth is not only for us but for all creation. The donkey and the ox recall the opening verses of the Prophet Isaiah: “An ox knows its owner and a donkey its master’s manger…” They also represent “all creatures great and small,” endangered, punished and exploited by human beings. They too are victims of the Fall. Christ’s Nativity is for them as well as for us.

There is something about the way Mary turns away from her son that makes us aware of a struggle different than Joseph is experiencing. She knows very well her child has no human father but she does not know her child’s future, only that it is clear from the circumstances of his birth that his way of ruling is in absolute contrast to the way kings rule. The ruler of all rules from a manger in a stable. His death on the cross will not surprise her. It is implied in his birth.

We see that the Christ child’s body is wrapped “in swaddling clothes.” In icons of Christ’s burial, you will see he is wearing similar bands of cloth, as does Lazarus in the icon of his raising by Christ. In the Nativity icon, the manger looks much like a coffin. In this way the icon links birth and death. The poet Rilke says we bear our death within us from the moment of birth. The icon of the Nativity says the same. Our life is one piece and its length of much less importance than its purity and truthfulness

Some versions of the icon show more details, some less.

Normally in the icon we see angels who are worshiping God-become-man. Though we ourselves are rarely aware of the presence of angels, they are deeply enmeshed in our history and we know some of them by name. This momentous event is for them as well as us.

Often the iconographer includes the three wise men who have come from far off, whose close attention to activity in the heavens made them come on pilgrimage in order to pay homage to a king who belongs, not to one people, but to all people, not to one age but to all ages. They represent the world beyond Judaism.

Then there are the shepherds, the simple people summoned by angels to respond to Christ’s birth. Throughout history it has in fact been the simple people who have been most uncompromised in their response to the Gospel, who have not buried God in footnotes. Not the wise men but the shepherds were permitted to hear the choir of angels singing God’s praise.

On the bottom right of the icon often there are one or two midwives washing the newborn baby. The detail is based on apocryphal texts concerning Joseph’s arrangements for the birth. Those who know the Old Testament will recall the disobedience of midwives to the Egyptian Pharaoh; thanks to one of them, Moses was not murdered at birth. In the Nativity icon the midwife’s presence has another still more important function, underscoring Christ’s full participation in human nature.

Iconographers may leave out or alter various details, but always there is a ray of divine light that connects heaven with the baby. The partially revealed circle at the very top of the icon symbolizes God the Father, the small circle within the descending ray represents the Holy Spirit, while the child is the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, the Son. At every turn, from iconography to liturgical text to the physical gesture of crossing oneself, the Church has always sought to confess God in the Holy Trinity.

The symbol is also connected with the star that led the magi to the cave.

Orthodoxy often speaks of Christ in terms of light and this, too, is suggested by the ray connecting heaven to the manger. “Our Savior, the dayspring from on high, has visited us, and we who were in shadow and in darkness have found the truth,” the Church sings on Christmas, the Feast of Christ’s Nativity According to the Flesh.

The iconographic portrayal of Christ’s birth is not without radical social implications. Christ’s birth occurred where it did, we are told by Matthew, “because there was no room in the inn.” He who welcomes all is himself unwelcome. From the first moment, he is something like a refugee, as indeed he soon will be in the very strict sense of the word, in Egypt with Mary and Joseph, at a safe distance from the murderous Herod. Later in life he will say to his followers, revealing the criteria of salvation, “I was homeless and you took me in.” We are saved not by our achievements but by our participation in the mercy of God — God’s hospitality. If we turn our backs on the homeless and those without the necessities of life, we will end up with nothing more than ideas and slogans and be lost in the icon’s starless cave.

We return at the end to the two figures at the heart of the icon. Mary, fulfilling Eve’s destiny, has given birth to Jesus Christ, a child who is God incarnate, a child in whom each of us finds our true self, a child who is the measure of all things. It is not the Messiah the Jews of those days expected — or the God we Christians of the modern world were expecting either. God, whom we often refer to as all-mighty, reveals himself in poverty and vulnerability. Christmas is a revelation of the self-emptying love of God.

Source: In Communion