They say it is impossible to get Russians out into the streets; that no more than several hundred people would routinely come to opposition rallies.

That’s definitely true of rallies and any sorts of gatherings. But there is one exception. In recent years, the Virgin Mary and some of Christianity’s greatest saints, most of them dead for centuries, were able to cause tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of Russians to stand in lines for hours, or march in processions for miles, in snow and rain, freezing temperatures and steaming heat.

I am talking about the immense popularity of relics, wonder-making icons or other holy objects, commonly known in Russian as svyatyni – a phenomenon largely forgotten in the Christian West, but very much alive in the Christian East and really flourishing in today’s Russia.

A remarkable procession is currently taking place in Russia, something one would have a hard time imagining in any other modern country except perhaps some parts of Spain, Italy, Greece or Latin America. But the scale is unprecedented.

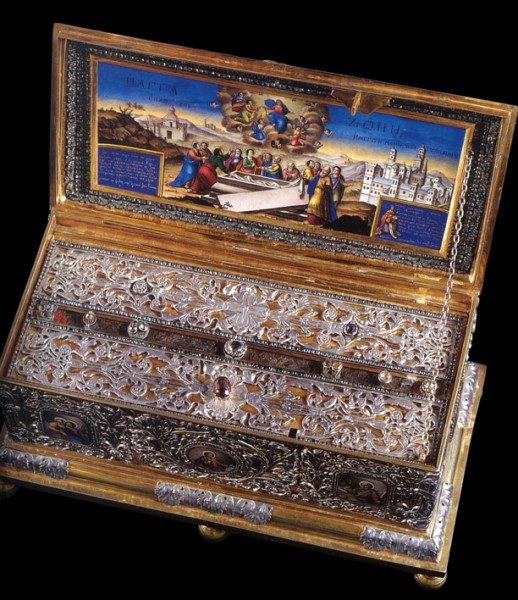

The Belt of the Virgin Mary, otherwise referred to as the Precious Sash, or Cincture, of Our Most Holy Lady Theotokos – the holy treasure of the Vatopedi Monastery on Mount Athos in Greece, is travelling abroad for the first time. The Belt is travelling in style. It flies in a private jet, chartered by the tour’s organizer – the influential St. Andrew Foundation, and is accompanied by six Vatopedi monks. In St. Petersburg, it was welcomed by none other than Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. In Yekaterinburg, Russia’s fourth largest city, Governor Alexander Misharin and the region’s bishop, Metropolitan Kirill, met the relic with the guard of honor before a procession of some 15,000 people took it to the cathedral.

Photo © St. Andrew's Foundation

The numbers are stunning indeed. In St. Petersburg, estimated one million people came to venerate the Belt in three days and nights, according to the local media. People stood in line for twelve to fourteen hours to be able to kiss the silver box containing the piece of camel wool fabric believed to have been woven and worn by the Virgin Mary, and take a small band blessed on the relic. In Yekaterinburg it was 300,000, in Krasnoyarsk – 100,000. The relic has already been to the country’s Far East – in Vladivostok, and the Far North – in Norilsk, beyond the Arctic Circle. Volgograd and Stavropol in the South are in the days to come. And it is hard to imagine what kind of crowds will gather in Moscow when, by the end of November, the relic arrives in the capital before leaving Russia for good.

© Photo © St. Andrew's Foundation. The line to kiss the relic in St. Petersburg.

Of course, many in the lines are women – the belt is believed to cure infertility. But there are not only women. People come from other towns and cities, wait for hours if not days, stand in usually calm prayerful lines – so unlike the lines in airports or Soviet-era lines for sausage. The other day, a colleague, whom I had not suspected of particular religiosity, approached me asking about the dates when the Belt would be in Moscow. He is certain to go and stand in line as long as it takes. People discuss, including in blogs and on social networks, whether it is worth doing and what is the meaning of it. Is it the sign of deep belief and special predisposition to holiness? Or a rudiment of paganism? How Christian is it really?

My answer is – it’s all of the above. Moreover, veneration of, or respect for, or even hunting for various sorts of svyatyni is a core element of Russian religiosity.

“Russia knew neither Reformation nor Counterreformation with their explanations, symbolic interpretations and the uprooting of medieval idol-worshiping,” famous Russian Christian scholar George Fedotov wrote in his 1946 classic The Russian Religious Mind. “The Russian peasant, even in the 19th century, lived as if in the Middle Ages. Many foreigners have written that this people is the most religious in Europe. But in essence, it is more about various degrees of maturity rather than about substantial peculiarities of spirit and culture. The same historical factors have preserved the religious perceptiveness of the Russian people in the era of rationalism, while not touching the many pagan customs, cults and even the pagan worldview both within the church and outside it.”

One million people came to venerate the Belt in St. Petersburg.

Indeed, what was the original reason for building the Amiens Cathedral – the greatest medieval structure in Europe? It was the head of St. John the Baptist – one of the thousands of relics that Crusaders plundered from the Christian East to move to the West. Today, not so many Roman Catholics come to Amiens for that. But, with the opening of the borders and globalization, the Orthodox Christians have begun to, and its Catholic custodians are happy to welcome the new pilgrims. Or come to the Notre Dame de Paris on the first Friday of the month, when Christ’s Crown of Thorns is taken out for veneration — more than a half of the worshippers would be Orthodox, many of them – Russian.

Quite a few years ago I spent about an hour in the back of the Cave of the Nativity in Bethlehem, both praying and watching the multitude of people speaking all sorts of languages coming to the altar on the site where Jesus is believed to have been born. There was a group of American Protestant pilgrims, wearing identical t-shirts and badges with some Christian slogan on it. They spoke loudly, laughed, took pictures and one merry couple even sat on the altar – certainly, not knowing it was the altar or not knowing what it means – to have their picture taken. Shortly after them, came a group of Russian tourists, not even pilgrims. They were quiet. Women wore some awkward-looking head covers – they were clearly unprepared to be in the church. They lit candles, made the sign of the cross, knelt before the star on the floor on the site of the Nativity. They were not your regular church goers, but they were full of awe before the svyatynya they were near. I remember thinking back then: these American Protestants came here with the purpose of pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and they definitely knew a lot more about Christianity, including the Holy Scripture, than these Russian tourists. It is simply not part of their culture to understand – or feel – what is a holy place.

For many people the hunt for the holy is, of course, magic. A desire for a quick solution to their problems. Or some solution. Or, maybe, the first time they would pray. Who knows? And if the svyatynya is on tour from abroad, if access to it is limited one way or the other – so the more popular it would be.

Eleven years ago, one of the first times a “touring holy” was in Moscow – it was the head of St. Panteleimon (Pantaleon) the Healer, also from Mount Athos, I spent eight hours waiting in line to be able to venerate it. If someone had told me a day before that I’d be able to wait so long in line, I’d laugh at the person’s face. But it was a very special line – it was easy to wait, easy to stand, people prayed all around you, and so did you. The line itself was a sort of liturgy too. Closer towards the end of the line, sellers appeared walking along the line offering paper icons and brochures. “You cannot pray to the icons – it is idolatry,” a teenage girl who I had remembered standing behind me for hours now, told her friend, as if reciting from some Protestant literature. I could not hold myself, turned back to her and said: “If that is how you believe, what have you been doing here for seven hours plus? Because the relics are in essence the same as an icon?”

She was unsettled by the question at first. And then her eyes glazed and she said dreamily: “And what if something happens?” She wanted a miracle too.

Source: RIANOVOSTI