Most of the time we think we know who we are. But do we, in fact, know in the full and profound sense who we are? One text that is very important for the Orthodox understanding of the human person is Psalm 64:6 [LXX 63:7]—”The heart is deep.” That means the human person is a profound mystery. There are depths—or if you would like, heights—within myself of which I have very little understanding.

Most of the time we think we know who we are. But do we, in fact, know in the full and profound sense who we are? One text that is very important for the Orthodox understanding of the human person is Psalm 64:6 [LXX 63:7]—”The heart is deep.” That means the human person is a profound mystery. There are depths—or if you would like, heights—within myself of which I have very little understanding.

Who am I? The answer is not at all obvious. My personhood as a human being ranges widely over space and time. And indeed it reaches out beyond space into infinity, and beyond time into eternity. Our human personhood is created, but it transcends the created order. As is said in 2 Peter 1:4, I am called to be a “partaker of the divine nature.” I am called to share, that is to say, in the uncreated energies of the living God. Our human vocation is theosis, deification, divinization. As St. Basil the Great says, “The human being is a creature that is called to become God.”

I am reminded of the story of the Fall at the beginning of Genesis, of the promise of the serpent, who says to Eve, “You shall be as God” (Genesis 3:5). The irony behind that story is that this was exactly the divine intention. The humans were indeed called to divine life. But the Fall consisted in the fact that Adam and Eve grasped with self-will that which God, in His own time and way, would have conferred upon them as a gift.

The limits of our personhood are very wide-ranging indeed. We should adopt a dynamic view of what it is to be a person. We shouldn’t think that our personhood is something fixed. To be a person is to grow. To be on a journey. And this journey is a journey that has no limits, that stretches out forever, that goes on even in heaven. Some people have an idea of heaven as a place where you do nothing in particular. But surely that is deceptive. Surely heaven means that we continue to advance by God’s mercy from glory to glory. Heaven is an end without end.

St. Irenaeus remarks, “Even in the age to come God will always have new things to teach us, and we shall always have new things to learn.” So even in heaven, we shall never be in a position to say to God, “You are repeating Yourself. We have heard it all before.” On the contrary, heaven means continuing wonder and unending discovery. To quote J.R.R. Tolkien in The Hobbit, “Roads go ever ever on.”

Now there is a specific reason for this mysterious and indefinable character of human personhood. And this reason is given to us by St. Gregory of Nyssa, writing in the fourth century. “God,” says he, “is a mystery beyond all understanding.” We humans are formed in God’s image. The image should reproduce the characteristics of the archetype, of the original. So if God is beyond understanding, then the human person formed in God’s image is likewise beyond understanding. Precisely because God is a mystery, I too am a mystery.

Now in mentioning the image, we’ve come to the most important factor in our humanness. Who am I? As a human person, I am formed in the image of God. That is the most significant and basic fact about my personhood. We are God’s living icons. Each of us is a created expression of God’s infinite and uncreated self-expression. So this means it is impossible to understand the human person apart from God. Humans cut off from God are no longer authentically human. They are subhuman.

If we lose our sense of the divine, we lose equally our sense of the human. And that we can see very clearly from the story, for example, of Soviet communism in the 70 years which followed the revolution of 1917. Soviet communism sought to establish a society where the existence of God would be denied and the worship of God would be suppressed and eliminated. At the same time, Soviet communism showed an appalling disregard for the dignity of the human person.

I think those two things go together. Whoever affirms the human also affirms God. Whoever denies God also denies the human person. The human being cannot be properly understood except with reference to the divine. The human being is not autonomous, not self-contained. I do not contain my meaning within myself. As a person in God’s image, I point always beyond myself to the divine realm.

I remember a visit in my student years in Oxford from Archimandrite Sophrony, the disciple of St. Silouan of Mt. Athos. He gave a talk on Orthodoxy, and there was a discussion afterwards. Towards the end, the chairman said, “We have time for just one more question.” Somebody got up at the back of the audience and said, “Fr. Sophrony, please tell us—what is God?” And Fr. Sophrony answered very briefly, “You tell me—what is man?” God and the human person are two mysteries that are interconnected, and neither can be understood apart from the other. “In the image of God” means there’s a vertical reference in our personhood. We can only be understood in terms of our link with the divine.

But then, let’s think of another point. “In the image of God” means in the image of the Trinity. As St. Gregory the Theologian says, “When I say God, I mean Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” That is what as Christians we mean by God. We don’t understand God as a series of abstractions. We understand God as three Persons. And that we see very clearly from the Creed. We begin in the Creed by saying, “I believe in One God.” And then we don’t continue by saying, “Who is an uncaused cause, who is primordial reality, who is the ground of being.” This is the way many modern theologians speak. But in the Creed we say, “I believe in One God . . . the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” We continue, that is to say, in specific personal terms.

God for us is Trinity. And if we’re in the image of God we’re in the image of the Triune God. What does that mean for our understanding of our personhood? Let’s think first of the Trinity, and then of ourselves.

“God is love” (1 John 4:8). And St. John in the same chapter says, in verse 18, “There is no fear in love; but perfect love casts out fear.” In true love there is no exclusiveness, no jealousy. True love is open, not closed. God is love. There is no fear in love. And so God is not the love of one. God is not love in the sense of being self-love, turned in upon itself. God is not a closed unit. God is not a unit, but a union. God is love in the sense of shared love, the mutual love of three Persons in one.

When the Cappadocian Fathers in the fourth century are describing God, one of their key words is koinonia, meaning fellowship, communion, or relationship. As St. Basil says in his work on the Holy Spirit, “The union of the Godhead lies in the koinonia, the interrelationship, of the Persons.” So this then is what the doctrine of the Holy Trinity is saying: God is shared love, not self-love. God is openness, exchange, solidarity, self-giving.

Now, we are to apply all this to human persons made in the image of God. “God is love,” says St. John. And that great English prophet of the eighteenth century, William Blake, says, “Man is love.” God is love, not self-love but mutual love, and the same is true then of the human person. God is koinonia, relationship, communion. So also is the human person in the Trinitarian image. God is openness, exchange, solidarity, self-giving. The same is true of the human person when living in a Trinitarian mode according to the divine image.

There’s a very helpful book by a British philosopher, John Macmurray, entitled Persons in Relationship, published in 1961. Macmurray insists that relationship is constitutive of personhood. He argues that there is no true person unless there are at least two persons communicating with each other. In other words, I need you in order to be myself. All this is true because God is Trinity.

From this it follows that the characteristic human word is not “I” but “we”. If we are all the time saying, “I, I, I,” then we are not realizing our true personhood. That’s expressed in the poem of Walter de la Mare, “Napoleon”:

What is the world, O soldiers?

It is I:

I, this incessant snow,

This northern sky;

Soldiers, this solitude

Through which we go

Is I.

Whether the historical Napoleon was actually like that or not, de la Mare’s point is surely valid. Self-centeredness is in the end coldness, isolation. It is a desert. It’s no coincidence that in the Lord’s Prayer, the model of prayer that God has given us, and which teaches what we are to be, the word “us” comes five times, the word “our” three times, the word “we” once. But nowhere in the Lord’s Prayer do we find the words “me” or “mine” or “I”.

In the beginning of the era of modern philosophy in the early seventeenth century, the philosopher Descartes put forward his famous dictum, “Cogito ergo sum“—”I think therefore I am.” And following that model, a great deal of discussion of human personhood since then has centered round the notion of self-awareness, self-consciousness. But the difficulty of that model is that it doesn’t bring in the element of relationship. So instead of saying “Cogito ergo sum—I think therefore I am,” ought we not as Christians who believe in the Trinity to say, “Amo ergo sum“—”I love therefore I am”? And still more, ought we not to say, “Amor ergo sum“—”I am loved therefore I am”?

One modern poem that I love particularly, by the English poet Kathleen Raine, has exactly as its title “Amo Ergo Sum.” Let me quote some words from it:

Because I love

The sun pours out its rays of living gold

Pours out its gold and silver on the sea.

Because I love

The ferns grow green, and green the grass, and green

The transparent sunlit trees.

Because I love

All night the river flows into my sleep,

Ten thousand living things are sleeping in my arms,

And sleeping wake, and flowing are at rest.

This is the key to personhood according to the Trinitarian image. Not isolated self-awareness, but relationship in mutual love. In the words of the great Romanian theologian Fr. Dumitru Staniloae, “In so far as I am not loved, I am unintelligible to myself.”

If, then, we think of the divine image, we should not only think of the vertical dimension of our being the image of God; we should also think of the Trinitarian implication, which means that the image has a horizontal dimension—relationship with my fellow humans. Perhaps the best definition of the human animal is “a creature capable of mutual love after the image of God the Holy Trinity.” So here is the essence of our personhood: co-inherence; dwelling in others.

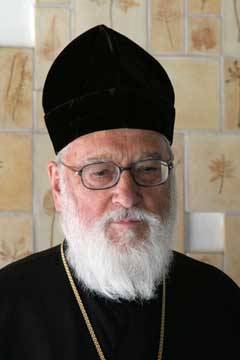

This article is adapted from Bishop Kallistos Ware’s lecture series, “The Human Person in Orthodox Spirituality,” presented at the Eagle River Institute of Orthodox Christian Studies, Eagle River, Alaska, in August 1998. Bishop Kallistos is a Greek Orthodox bishop in Oxford, England, and during 1966 to 2001 he lectured in Eastern Orthodox Studies at the University of Oxford. His books include The Orthodox Church, The Orthodox Way, and The Inner Kingdom.

This article originally appeared in AGAIN Vol. 27 No. 2, Summer 2005.