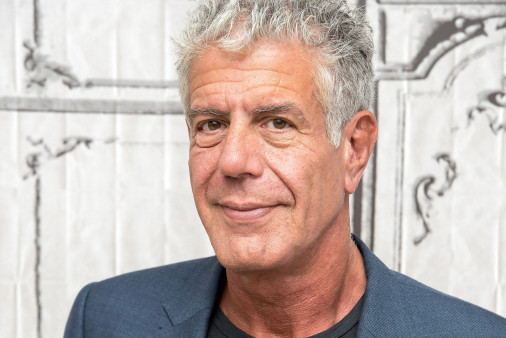

If you don’t know who Anthony Bourdain is it’s probably because you hate traveling and good food. He was THE perennial all-star travel and food critic; he held the job that I, and anyone with any sense of sense, dreamed of having.

And besides the actual Anthony Bourdain – the witty, sarcastic, crass storyteller, chef extraordinaire – I think many fans have a place in their souls which could be called the ‘Bourdain soul’; that special place in the psyche lost in dreams of endless travel and culinary luxury. This dream would remain pure fantasy if it were not for a select few people, like Anthony Bourdain, who actually lived the dream.

Now, I’m not totally foolish. I know from the dozens of celebrity suicides in the past that the luxurious life does not guarantee a paradise of soul; I know from endless readings of my spiritual heroes of the faith – the saints, martyrs and ascetics – that luxury is actually the last place one will find paradise of soul; I know from my studies and clinical experience in mental health that luxurious living has nothing to do with eliminating anxiety and depression, but can often amplify them; etcetera.

But Bourdain, dammit, Bourdain made me hold on to that last, infinitesimally small portion of my soul that still believed the dream. His passing today by suicide marks the passing of my own Bourdain soul, the final burying of the fantasy once and for all.

He had it all. He fought back from a life of drug abuse in his youth to become a world renown chef and accomplished author; landed an unbelievably successful travel show which kept him globetrotting for decades to every beautiful destination on the planet; his palate was filled daily with the finest food and drink ever produced; he became an avid jiu jitsu practitioner in his 50’s and claimed that he was living in the best physical condition of his life; he had wealth; he had fame; and… and apparently it wasn’t enough.

He had it all. He fought back from a life of drug abuse in his youth to become a world renown chef and accomplished author; landed an unbelievably successful travel show which kept him globetrotting for decades to every beautiful destination on the planet; his palate was filled daily with the finest food and drink ever produced; he became an avid jiu jitsu practitioner in his 50’s and claimed that he was living in the best physical condition of his life; he had wealth; he had fame; and… and apparently it wasn’t enough.

What was missing?

Don’t most of us have this nagging question every time we are shocked by another celebrity suicide? Yes, but this was different. We all sort of suspect that most celebrities live in a private, hellish, inner prison, though their outward life tells a different story, but not Bourdain. And not because he was without angst. It was precisely because of his angst and his ability to express it that made him seem less likely than others to end his life. Those who always have it together, those are the ones you watch out for.

Answering the “What was missing?” question is usually an act of presumptive foolishness. Only Bourdain knew what was missing for him. But it doesn’t stop me from wondering. Was it simply that he, like many before him, had hit the plateau of perceived success in life and in the course of realizing his dream realized it was just a dream? What if the plateau was a daily reminder that he was missing what he was really after? What if the fine food and wine were daily reminders that the belly is never satisfied? What if he had a sudden loss-of-home feeling every time he saw his own face in the mirror? On TV?

These are common thoughts I have every time a celebrity takes his or her own life, but… not this guy, the guy whose job was so dreamy that I would clean all the toilets in New York with my tongue to have. Not him. What could possibly be missing? How can you kill yourself – in Strasbourg, France! Not exactly the most depressing place ever.

Whatever the reason, Bourdain’s story has many lessons. For me, I am reminded that life is not only short, precious, and unpredictable, but that people are sad – often those you least expect. Sadness is okay, it’s part of being human, but the sort of sadness that can be a matter of life and death can go unnoticed by those closest to us since it is often (and as a clinician I’m tempted to say always) a matter of inner desperation, not a matter of external lack. If external goodies – pretty stuff, good tasting stuff, adventurous stuff, and lots of it – ever had the power to give meaning to life, to rescue one from suicide, then surely it would’ve saved Bourdain. Goodies are powerless to add meaning to life, and ultimately rob us of true happiness. As Viktor Frankl once said, “People do not want to be happy. They want a reason to be happy.” Bourdain reminds me to always remain conscious of my “reason” to be happy, and to help others remember theirs.