There are many situations in our struggle for holiness that require us to try harder. Some such situations might include getting out of bed to pray—assuming that you went to bed at a reasonable hour the night before and have slept adequately. Not getting out of bed to pray just because one doesn’t want to is a classic situation that might call for one to try harder. Another situation that might call for trying harder is the use of foul, disrespectful or sarcastic language. Just because you have habituated yourself to speaking in unkind or crude ways and it feels “natural” for you to speak that way, doesn’t mean that with a little more effort, by trying a little harder just to keep your mouth shut, you can’t change your habits of speech. There are many aspects of our Christian struggle for repentance that require effort on our part, that require us to try harder when we fail.

However, this post is not about those times or situations in which trying harder might be part of the spiritual therapy we need to practice in order to overcome a weakness or sin in our life. This post is about the times when trying harder is not the answer, when trying harder (or thinking that you have to try harder) may even be counter productive, misleading and even keeping you stuck in a cycle of meaningless confusion, guilt and pain.

Often there are painful circumstances in our life that we cannot help thinking that we have played some role in bringing about. These circumstances might include failures in relationships, loved ones who have (or seem to have) rejected God and who are living self-destructive lifestyles. It might include difficult financial, health or even psychological and addiction problems. It might include difficult relationships that we cannot avoid in family, work or school, relationships that sadden, anger or frustrate us, but that we can do nothing about. Often it happens that in such painful and frustrating circumstances we assume, or even know for sure, that part of the reason for the pain we experience and that our loved ones experience is our fault. But where we make our mistake is in thinking that we can fix it.

Certainly, broken relationships and failures require repentance and humility on our part, especially when we can identify specific mistakes we have made or sins we have committed. And when we can identify specific mistakes or sins, it is sometimes (but not always) helpful for us to humble ourselves and confess our sins and failures to the people affected. However, this is not always the case. This is a matter that requires discernment, and the advice of a spiritual father or mother or other wise person in your life can help you in discerning whether or not, when and how public confession might be a healing action in a specific relationship. And when there is no specific sin or fault or failure that you can identify—just a sense of guilt—then I think it is usually best just to confess your sins only to your priest.

One of the realities of the Orthodox Christian worldview is that to one extent or another we are all responsible for the suffering, sin and brokenness in the world. Like Adam, our tendency is to blame others for the mess the world is in, but sometimes we cannot avoid seeing our complicity or even our fault in the pain and suffering especially in the lives of those closest to us. But like Adam after eating the forbidden fruit, there is nothing that can be done about it except to confess it. The apple cannot be hung back onto the tree. The brokenness that I have brought into the world cannot be fixed by me. It can only be fixed by our Saviour. But we can confess. We see in great saints, such as St. Isaac the Syrian and St. Silouan of Athos, and many others, that they confess the sins of the whole world as though they themselves are responsible for all of the sins, all of the pain, and all of the brokenness in the world. Most of us, however, only see the smallest fraction of our sin, of our complicity in the the brokenness and pain of the whole world. And so that’s what we can do: we can confess our sin, in as much as we see it.

But even confession, public or otherwise, often does not change the situation nor relieve the pain we are experiencing at the suffering in our own lives and in the lives of those around us. And this pain, often a pain we cannot even find words to express, seems to be screaming at us that we must do something, that we must try harder to fix it. But there is no trying harder.

One reason why there is no trying harder is that we have already tried as hard as we can for a long time, years perhaps, to think of what we could do differently, how we might pray differently, or what we might say or how we might sacrifice ourselves in some way to make the pain go away, to heal the brokenness in our relationships, in our lives and in the lives of our loved ones. Another reason why there is no trying harder is that we are not and cannot be the Messiah. We can suffer. We can weep with those who weep. We can pray and “offer ourselves and each other and our whole life to Christ our God.” But we cannot save. Only God saves. Trying harder is not the answer.

So what must we do? Are we to do nothing? This question reveals, I think, a profound misunderstanding we have about the spiritual life.

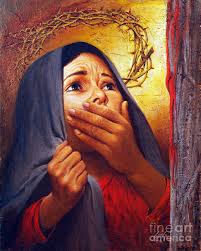

Think for a moment about the Mother of God standing at the Cross of Jesus. What could She do? Was She superfluous? What is the meaning of Her presence at the Cross except to suffer with Her Son? Her suffering is not meaningless. I will go further and say that no suffering is meaningless, if it is understood as a sharing in the suffering of God, if it is offered to God as a participation in His suffering. Isn’t this also what St. Paul says when he speaks of filling up in the sufferings of his own flesh what is “lacking” in the afflictions of Christ? (Colossians 1:24).

And yet, it doesn’t feel like suffering with Christ. It feels lonely and desperate. It feels as though I am abandoned and as though no one understands or could ever understand the pain and frustration and despair I feel. It feels, almost certainly, much like the Mother of God felt standing next to the Cross of Her Son.

And what could She do? She could only endure the pain. She could weep in despair, and await the Resurrection. And very often in our lives, that is what we can do; it’s all we can do. Very often in the Christian life what we are to do is to suffer, to endure the pain, confusion and feelings of despair, awaiting the Resurrection, the Act of God bringing salvation. This is not doing nothing. This is doing what the Mother of God did and does. This is sharing in the sufferings of Christ. This is being the Body of Christ.