Russians generally have a bad rap as being dour and grumpy. Some Russians will even agree with this characterization, making a point to ridicule how Americans always smile. But there’s a few weeks in the year when no Russian will pretend to be anything but joyful. One of these is, obviously, Paschal Week. But another almost equally festal week is the week before Lent, called Maslenitsa.

This week’s article is a translation from Foma Magazine. The original Russian can be read here.

Maslenitsa: the meaning, history, and traditions of “Russian Mardi Gras”

The last day of the week before Lent is called “Forgiveness Sunday.” It’s a fitting end to the series of preparatory weeks before Lent. This “introduction” to the Fast lasts 22 days, and during this time, the Church “gives the tone” for the faithful’s entry into a different spiritual space.

This far-sighted attention to Lent is completely justified, because the Great Fast is the heart of the entire liturgical year in most Christian churches. Lent is a special time. As the poet Natalia Karpova said, it’s “seven slow weeks, given to you for repentance.” The rhythm of life changes. Naturally, radical changes in the soul don’t occur in an hour, and so a serious preparation of the mind, the emotions, and the body is necessary.

If we study the history of this week, we find out that the preparatory rhythms of “Cheesefare Week,” as it’s also called, are among the oldest traditions in the Christian Church. They appeared thanks to the influence of the Palestinian monastic tradition. Palestinian monks spent nearly the entire 40 days of the Fast completely alone in the desert. By the last week of the fasting period, Holy Week, they returned to the monastery, but not all of them. Some of them would have died in the desert.

Since the monks understood that every new Lent could be their last, they asked forgiveness of each other on the Sunday before. This is where “forgiveness Sunday” comes from.

The special allowance to eat dairy on Wednesday and Friday is also of monastic provenance. After all, what is the desert? It’s a lack of food, and sometimes, even water. Naturally, the monks needed to gather physical strength before embarking on this labor. The monks didn’t eat meat (they never ate meat), so this week was essentially fast-free for them.

Laypeople assumed this monastic tradition, and the meaning changed somewhat. After all, laypeople don’t go into the desert, so they have no especial need to load up on proteins. For laypeople, this week’s feasting has a different focus. The world has many temptations, and abandoning all of them suddenly can be dangerous. Therefore, the limitations of the Fast are introduced slowly. This week, for example, meat is no longer allowed, and neither are weddings, interestingly enough. However, joyful feasting is definitely the order of the day, provided it’s still moderated somewhat. After all, Lent is at the doorstep.

The Pre-Christian History of Maslenitsa

Maslenitsa is actually an old pagan holiday known in Rus even before the coming of Christianity. It must immediately be said that the Church has never considered Maslenitsa to be part of its tradition, and there is no feast in the Church calendar called Maslenitsa. “Cheesefare Week” only happens to coincide with it.

However, in a certain sense, Christianity has never been intolerant of paganism. On the contrary, the Church often “baptized” traditional pagan holidays and feasts, infusing them with new meaning, thereby making the cultural transition from pagan to Christian more organic.

So if the Church didn’t make Maslenitsa part of the Church calendar, it did denude it of its sacred character. Instead, it made this vivid and even grotesque period into a week of rest, relaxation, and feasting.

The Meaning of Pagan Maslenitsa

We can start with the fact that in ancient times this holiday was far more multi-faceted than in the centuries immediately preceding the Revolution. At its heart lies an idea common to all pagan religions: the cult of the “cycle of time.” The older the civilization, the more it tends to accent this idea of time’s repetitiveness.

Ancient Slavic Maslenitsa was celebrated in early spring, when the day began to win its battle against the long night. This would be around March 21 or 22 according to our calendar. In old Rus, the first days of spring’s first month were always unpredictable. Warm weather could quickly be replaced by harsh frost, and vice versa. As I wrote in another post, “spring battles with winter.” Maslenitsa celebrates this final crossing from cold to warm, after which the spring triumphs over the winter. Life will soon again follow its more predictable rhythms.

Naturally, the coming spring was connected with fertility cults. The land resurrects, having absorbed the last of the winter’s snows, filling itself with “seed.” And now, people had to help mother Earth, to give the natural process a touch of the sacred.

Speaking more prosaically, the rites of Maslenitsa consecrate the earth, filling it with power to give abundant harvest. For peasants, the backbone of old Russian society, a good harvest is the only true wealth, so these rites were naturally important. In that sense, Maslenitsa was a kind of “pagan liturgy,” the peasants bringing an offering to nature and its elements instead of God.

Not only the land, but the peasants themselves receive the blessing of fertility for taking part in Maslenitsa. If you eat the food given by Mother-Earth, then you will also give life to another. The circle of life, the natural cycle of life and death and rebirth, were central to the pagan mindset. Life itself was the most important value, and everything else was a means to attaining it. That’s also why there was an element of ancestor worship in the early Maslenitsa celebrations.

After Christianity, the sacred meaning of Maslenitsa practically disappeared, leaving behind only its external trappings and slightly manic joy.

The Feast of Kolodii

An even older name for Maslenitsa is Kolodii. This is connected with a bizarre ritual that survived even to recent times in Ukraine and Belarus. During this entire week, in addition to the other rites associated with the week, the villagers celebrated “the life of the koloda.” They took a thick stick (a “koloda”) and dressed it as a human being. On Monday, the koloda “was born,” on Tuesday, it was “baptized,” on Wednesday it lived all the difficult moments of its life. On Thursday, it “died,” on Friday it was “buried,” and on Saturday, everyone “mourned it.” On Sunday was the culmination of Kolodii.

During this whole week, the women carried it around the village and tied it to all who were unmarried. This included those who had illegitimate children. Of course, no one wanted to be branded with this label, so the women-bearers had to be bought off. Colored ribbon, beads, plates, drinks, or sweets were considered appropriate.

The Blin

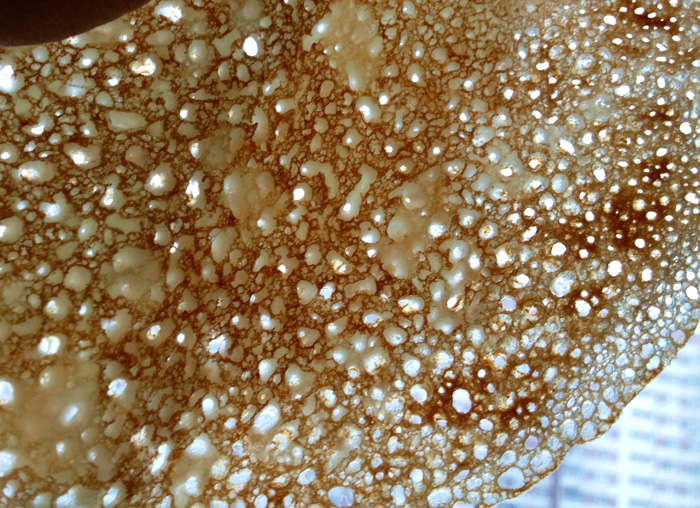

The food most associated with Maslenitsa is the thick pancake, the blin, that is still consumed in obscene amounts in any self-respecting Russian household. The famous Russian folklorist Afanasiev believed the blin to be a symbol of the sun, connecting the meal to the fertility rites of reborn spring. However, another possibility is that the blin is the ancient food-offering for dead ancestors, having a profound symbolic meaning.

It has a circular shape (a hint of eternity). It’s warm (reminding of earthly joy) and made from wheat, water, and milk (the elements of life). A custom that survived long into the 19th century testifies to the probability of this second hypothesis. On the first day of Maslenitsa, a few blini were left in the attic “to feed the departed” or given directly to the local poor, so that they would pray for the family’s departed relatives. Thus, it is still said, “The first blin is for remembrance.”

Some of the other ancient traditions of Maslenitsa week were also associated with the commemoration of the departed. One of these was the famous fist-fight so well depicted in Nikita Mikhalkov’s Oscar-winning film “The Siberian Barber”:

As you can see in the clip, these fights were quite dangerous. Sometimes people would die, harking back to ancient times when such fights were part of a sacrifice to Mother-Earth. The blood of fallen warriors was always the best offering to the gods.

The last victim of Maslenitsa was not human, however. An effigy of winter was triumphantly burned at the end of the week, and the ashes were scattered over the field. This was the final consecration of the soil, often accompanied by songs that would call the earth to bring forth abundant fruit in the coming year.