Source: Orthodox Church in America Homepage

Oskar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg are among the most commonly known people who have been recognized as taking extra-ordinary personal risks to help Jews and others targeted for extermination by Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Worker’s Party in Germany , 1933-1945.

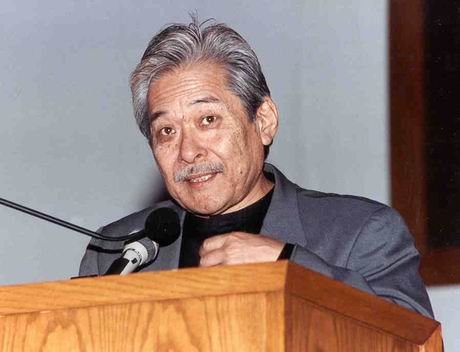

Perhaps the least well known is a Japanese diplomat, Chiune Sugihara (d. 1986), who only later in life admitted to his own heroic actions, and was recognized in 1985 by the State of Israel with its highest honor. Even less well known is that Sugihara was a convert to Orthodoxy.

Born on January 1, 1900 , Sugihara enrolled in Tokyo ’s Waseda University , which to this day is considered to be one of Japan ’s top private institutions with a flair for international affairs. He studied English, and then was received into the Foreign Ministry. An accomplished linguist, he was sent in the 1920’s to the Japanese language institute in Harbin , the capital of Manchuria , China . There he learned Russian and converted to Orthodoxy. Such were his skills that he participated in negotiations with Russia for the sale of the Manchurian Railway to Japan .

He rose through the diplomatic ranks with the linguistic and social abilities commensurate with his positions. Multi-lingual, he was sent to Finland in that late 1930’s, and with war pending was entrusted to be the one-man consulate for Japan to Lithuania in March, 1939. Six months later, Hitler invaded Poland , and refugees poured into Lithuania headed east. Then in June 1940, the Soviet Union invaded Lithuania as part of its spoils from its non-aggression pact with Germany , signed just before the invasion of Poland .

One month later, July 1940, the Soviet government informed all foreign consulates in Lithuania to leave. Instead of leaving, Sugihara requested and received a 20-day extension, leaving only himself and his Dutch counterpart as the only two consuls in Lithuania .

These two consuls, along with the Soviet attachй, soon found themselves inundated with requests from refugees, mostly Polish Jews, who could emigrate to the Dutch Caribbean. To get there, they had to pass through the Soviet Union and Japan . The Soviet Government insisted that they have a valid transit visa from Japan in order to exit from the Soviet Union .

Sugihara’s request to issue these visas was denied by the Japanese Government three times. He decided to disobey his superiors, and began on July 29 issuing visas to the crowds outside his consulate. Night and day he worked, and in the end when he had to leave on September 1, 1940 , he threw his visa stamp from his train compartment to the desperate crowd. These “Sugihara Survivors” were upon arrival in Japan interred at Kobe , and then scattered, with many Jews staying under the protection of the Japanese government in Shanghai , China for much of the war.

Sugihara stayed in the Foreign Ministry until 1945, and was then dismissed. Some reports indicate that this was done unceremoniously, other reports claim that he did receive a pension for his services. He then worked for an export company near Tokyo for much of his remaining life, dying in 1986.

These are the common facts of his life available in English. What remains hidden to this writer to date, and what may be of singular interest to the readers of “Jacob’s Well”, is why he converted to Orthodoxy, and what impact his faith may have played in his unique role during World War II.

At a minimum, it is important to not discount his decision to disobey his superiors. While this may seem not especially noteworthy in a time of great confusion such as war, such an action for most Japanese would be fraught with tremendous trepidation. Japan ’s historical, literary or cultural tradition contains very little, if any, sense of the “rugged individualism” found in America . While we are familiar with stories embracing the hero who defies all things in order to save the day, Japanese in contrast are more familiar with hearing of sacrifices nobly made for the greater good. Add to these the normal expectations of obedience required within any government ministry, and the magnitude of Sugihara’s defiance cannot be underestimated.

Answers may lie in a formal study of Sugihara’s life, especially his formative 20s while stationed in Manchuria and its capital, Harbin . We can only imagine the lost world of Harbin in the 1920s, which has been devastated over the years by Japanese occupation in the ‘30s, World War II and the Chinese Civil War in the ‘40’s, and the rampant destruction of Mao and his followers especially during the Cultural Revolution of the ‘60s. This writer recalls Harbin of the 1980’s as horribly poor, with architecture and street design a unique mix of Chinese and Russian.

What can be surmised of the milieu Sugihara encountered in Harbin ? What there might have lead him to Orthodoxy? We know that Harbin in the 1920’s was filled with White Russian refugees, and became an intellectual and cultural center of the White Russian diaspora. We know too that the Japanese Orthodox Church was at its peak in Japan , before it was decimated by the purges of the government in the 1930s. How these might have influenced Sugihara is unknown, and any insight readers of Jacob’s Well may have are invited to send their thoughts to the editor for further investigation.

While the complete story of Sughihara’s involvement in the Orthodox Church is not clear, it had, and in fact, continues to encourage a response in others. In her autobiography, Visas for Life, Sugihara’s wife Yukiko acknowledges that given he had been baptized as an Orthodox Christian she also agreed to be baptized, taking the Christian name Maria, and they were married in February, 1935 in Tokyo.

An article in the Los Angeles Times ( September 21, 2002 ) entitled, “Greek Orthodox Cathedral Is Reaching Beyond Ethnic Roots,” tells the story of the growing interaction between St. Sophia’s Church and the Latino neighborhood where it is located. The pastor, Fr. John Bakas, affirmed that part of the inspiration for him came in 1995 through an invitation from the mayor of Los Angeles to attend a ceremony honoring Sugihara. Learning for the first time about his efforts which had saved the lives of thousands of Jews, Fr. Bakas also heard directly from his family that Sugihara’s actions were “propelled by his faith” as a member of the Orthodox Church. “’Here’s a man who did not take the comfortable road, who reached out beyond himself and did something sacrificial in providing service to others at the expense of himself,’ Fr. John said, tearing up even today as he recounted the story. ‘Sugihara had a tremendous impact on how I perceive my ministry.’” <![endif]>

Suffice it to say that, in his quiet, modest way, Sugihara very much embodied the noble concept of Tolstoy’s prince. He sought neither fame nor fortune, merely saying “I may have to disobey my government, but if I don’t I would be disobeying God.”

Bibliography:

Levine, Hillel. In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust . ( New York : The Free Press, 1996).

Mochizuki, Ken. Passage to Freedom: The Sugihara Story. ( New York : Lee & Low Books, Inc., 1997). A book for children.

Sugihara, Yukiko. Visas for Life. ( San Francisco : Edu-Comm., 1995).

There is also considerable information on the Internet, especially on the website of the Holocaust Museum, Washington, D.C. http://www.ushmm.org/ – go to “Site Search”

[Special thanks to Jurretta Heckscher for help in researching this article.]

|

|