For eighteen years of my life I have worked in hospital; first as a student, then as a surgeon in the War and in the French resistance movement and then afterwards as a physician. This will explain why, in the course of my address I shall at times use ‘we’ instead of ‘you’. I do not wish you to take it as an offence that I appropriate to myself your virtues and your toils.

I wish to say a few words about a subject which exercises my mind, which is essential to belief in the life of all creatures and particularly to those who are engaged in doing something about the lives of others. I mean ‘Intercession’. In the life of man intercession is something much more essential and much more all-embracing than we normally think and sometimes much more dangerous and risky than we usually imagine. All too often it seems to us that to intercede simply means to make an act of good will or of sincere human concern; to remind God of the needs that he already knows so well, and to prompt him to do that which he is certainly prepared to do without our prompting. So often when we make intercessions we turn to God to tell him what he would tell us, if we had ears to hear and if we had attention and good will. Every word of intercession means that there is a need.

‘Whom shall I send?’ More often than not, when we have mentioned the need and the Lord has answered with this question—there is a silence within us. This is not to say that we are unwilling, but that we are unaware that our intercession must ‘take flesh’ and that it must become real and concrete in an act of self-offering and that our intercession does not end when we have told God of the given need.

I have already said that intercession is dangerous, but I do not mean this in any superstitious sense. The verb ‘to intercede’ comes from the Latin and it means ‘to take a step in order to stand between two conflicting parties’. We all know what it means to take a stand between conflicting parties when to intercede means a rebellion against God. ‘Blessed are the peacemakers: they shall be called the sons of God.’ I am using this translation—which is not usual for you—because this is exactly what the Greek text says—relating the peacemaking not to a general kinship with our Heavenly Father, but to the fact that we are, in Christ, his sons in the fullest and, shall I say again, in the most dangerous sense of the word. When the salvation of the world was at stake, the Son was sent by the Father to suffer and to die.

At the close of the ninth chapter of the Book of Job, in his despair, Job cries out

‘Where is he that will put his hand on my shoulder and on my judge’s shoulder? Who will take this step and stand between us, ready to pay the price of an act of intercession in order to unite us for ever?’

As far as the history of man is concerned, the Son of God—the Word-made-Flesh—paid the price of this act of love. But also in his flesh, in his real and true and perfect humanity, he forgave the enmity that existed, and brought man and God together. When the conflict is not between God and man-the-offender, but between man and the consequences of his godlessness—being severed from oneness with God—then we must be aware that God may also reply ‘Whom shall I send ?’ If we have interceded with sincerity and with truth in our hearts we must be prepared to respond ‘Here am I; send me’. And we must be prepared to go all the way. One of the most shocking things a person can do regarding someone who is in need is to be prepared to go part of the way and then to say ‘I am tired now’, and when I say ‘I am tired’ it always means ‘I am tired of you’. Either it means that the one who needs your help is taking too long to be cured or to be consoled (‘I thought it would be a short illness; an easy experience for me’)—or it means that ‘It is too long for my patience and for my short-lived charity’.

I remember the case of a girl who has an incurable illness for whom we have been praying in our Church for the last 16 years. One of my parishioners once said ‘Could we drop this name which comes back at every service?’ I said ‘You are tired of it; you are tired of hearing this name once a week! Do you not think that the girl may be tired of going downhill 24 hours a day, seven days a week throughout these 16 years?’ My parishioner was no worse than any of us. We do this same sort of thing at every moment. Someone comes to us who is in need and we step in, making an explicit act of intercession and then, after a while, this person disappears from our surroundings because we have walked out of his life and yet we continue with our intercessions for him—which is worst of all, because we witness to God that we are aware of the need, we witness that the need is still there and we witness to the fact that we have betrayed a need. We must always remember that an act of intercession may require not only that we should walk the mile that the person begs us to walk with him—but the two miles—the infinity of miles—miles that may lead from this earth to the grave—and beyond. This applies particularly to those who are suffering and ill with incurable diseases and who are gradually moving towards death.

One of the reasons why we so constantly fail when we are confronted with death is that we are usually afraid of saying that death is near. If we are attentive to what is going on in our own hearts, in warning this lonely person of the loneliness of dying, we shall find, if we probe deeply enough, that what we are frightened of is of helping him all the way, from this day forward to the day of the actual death. We are not prepared to die, hour after hour, with this person. Look at the Cross: the Mother of God stood there—she stood there, the Gospels tell us, without a word. An inaction which expresses the same word as she gave when the archangel promised her the birth of a Saviour: ‘Behold, the handmaiden of the Lord’—she stands there offering the last offering which is both him and herself. She lives and dies in him—and with him. This is an act of intercession and which in itself is a purpose for intercession.

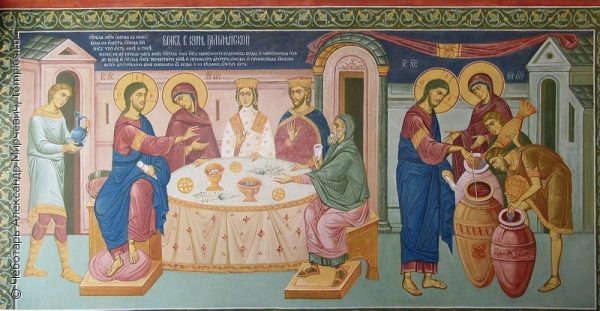

But intercession is not only stepping into a situation in order to bear together with God and with the sufferer or with the sinner. God stands at the door and knocks and, because there is no one to open this door, very often things do not happen in the lives of people. You will recall the verse from the Book of Revelation. How can one open the door to God in the problems of life and anguish and death of a man? In the Gospel according to Saint John there is the story of the marriage feast at Cana. There is a strange, a very strange conversation which goes on between Jesus and his mother; a conversation which we usually accept, in spite of its strangeness, because it is part of Holy Scripture. But either it has a meaning or we must recognize its absurdity. ‘They have no wine’ says his mother. ‘What have we got in common, woman; my hour is not yet come.’ The mother turned to the servants ‘Whatsoever he shall tell you, do.’

What does this conversation imply? Without giving you my full reasoning, I should like to tell you how I work it out and interpret it.

‘They have no wine.’ What she expects is a miracle: that is, an act of divine power, a divine act, that is possible only within the Kingdom of God— and not possible outside this Kingdom. For a miracle is not an act of overpowering by God—that would be absurd—but a miracle is the restoration of the harmony of the Kingdom in a world that surrenders, that becomes supple, obedient and loving. The son asks ‘Why are you asking me? Is it because, in the flesh, you are my mother? If this is the case, the Kingdom is as far from us as ever.’ Motherhood, even if it is a miracle, does not make the Kingdom present all the time and everywhere. ‘My hour is not yet come if you turn to me because you gave birth to me.’ And the mother answers and answers by giving evidence that the Son is within his own Kingdom and answers with the absolute, unlimited, unconditional faith which she showed on the day of the Annunciation. She makes an act of intercession which in itself is an act of faith. Turning to the servants she says ‘Whatsoever he commands you, do it’. When the Son heard this reply, when faith, sustained throughout a life, has established the Kingdom, then the miracle occurs. That which had been said a moment previously ‘My hour has not yet come’ has been blotted out by these words of the mother which shows that the hour of the Kingdom has come.

Such an act of intercession is something each one of us can make for every person in need, whether the person is in search of faith, or whether there is nothing but anguish or untold fear. We can make such an intercession in the Underground and in our homes; among friends and among foes; in the ward and in the operating theatre. We can always say ‘Lord, I believe. Come and stand here and I will stand in worship; I will stand in love; I will stand in obedience—ready to do whatever you tell me.’ That is an act of intercession far beyond the words of intercession which open to a man a gate or a door through which he can enter into any human situation. Such an act of intercession establishes the Kingdom upon earth and makes all miracles possible: but at a cost—the cost of our readiness not to seclude ourselves and not to limit prayer to words—but to make of all our lives an act of worship, and to be ready to pay the cost. We express the divine charity when we turn to God and say ‘Lord, look, there is need’ and the Lord says ‘Go: meet this need with all the love of your heart.’

I would like to finish by reminding you of the words of Saint Vincent de Paul to one of his daughters:

‘Remember, child, all the love of your heart will hardly be sufficient for people to forgive you for the good you are going to do. An act of charity can be cruel and hurtful if not done with a loving and a whole heart and with a whole commitment to God.’