This trip is especially memorable to me, down to some insignificant details that are firmly implanted in my mind. Perhaps this is because it was the last of my few exceptionally eventful trips to warring Chechnya. Or perhaps this is because an unforgettable meeting took place precisely during this last trip, on which everything else just became “hooked.”

It was the late spring or early summer of 1995, I do not remember exactly. I only remember that it was a parliamentary recess, when the deputies of the Federation Council and the State Duma had asked two of their colleagues to visit Chechnya to find out what was actually going on there following the seizure of Grozny, and to learn what could be expected there in the near future. Their task was to learn more and then inform the others after their return to Moscow. As a journalist I had the opportunity to accompany them, which I took.

Victor Kurochkin from the Federation Council and Victor Sheynits from the State Duma, who had invited me, had a far from simple task: to meet with one of the leaders of the Chechen militia (which would ideally be Aslan Maskhadov, who was in charge back then) and see for themselves in private conversation what the chances for a “peaceful settlement” were. That is, were there any realistic means to avoid future bloodshed and, at the same time, to preserve Chechnya as part of Russia? Therefore every morning, very early, we left our tiny hotel in the equally tiny town of Nazran and went to Grozny. There a certain local “acquaintance” would give us some “tips” on how we might find Maskhadov.

We went there every day, as if to work. We took the ruins of Grozny as something familiar. It was even difficult to remember how the city had looked before, even though I had been there before the war. Our attempts to find the leader were fruitless, but we did not lose heart. I especially did not, because I had already had enough information as a journalist. Besides, apart from the common goal the three of us shared, I had my own as well.

Those who followed the fighting in Grozny on television might still remember the story about the Archangel Michael Church. While the sounds of cannonade and booming were heard in the background, several Russian women in the middle of this terrible nightmare stood in front of a church… They said:

“When it all began, we gathered here; the Lord will protect us through the prayers of the Archangel Michael!”

So, of course, I very much wanted to go to that church and see what had happened to it and those women. Likewise, I wanted to talk with the church’s rector, Fr. Anatoly Chistousouv. In fact, I wanted to meet him more than Maskhadov.

When I finally understood that there was no opportunity for me to leave our group without putting our main task at risk, I asked my traveling companions to stop by that church together. I was very glad and grateful to them when they readily agreed.

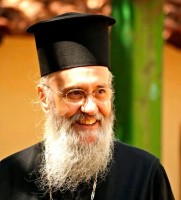

… A quick look was enough to understand that the war had not had mercy on the church. However, it had had mercy on (or, to be more exact, the Lord had preserved) those who had come with hope in God’s mercy under His shelter. The church itself had burned down, but its rector, Fr. Anatoly, had saved the antimension from the fire and continued to serve in the baptistery, which was situated on the church’s premises. It could have been a gatehouse, but I do not remember exactly.

Everything around the place was in ruins… There was a dust that seemed to hang in the air without landing on the ground. It was a dust that mixed gunpowder, brick remains, lime, and human horror, pain, and sufferings. This mixture then permeated everything.

At the very heart of all of this was a Russian priest with a meek and surprisingly calm and peaceful face with his congregation. I do not think these were only regular parishioners; they were simply people who were scared and had no other place to go. We talked with Fr. Anatoly and he told me how the church had caught on fire, how he had rescued the antimension from it, and how they had celebrated Pascha. People slowly gathered around us, especially around Fr. Anatoly. I looked at this and tears filled my eyes. I suppose I understood what a pastor and his flock actually meant for the first time in my life, because they were truly near him like the sheep with their shepherd. They had no one, save for God and the priest, who could protect them and was needed by them. Everything was very difficult and frightening there, but extremely authentic; probably because of the situation, there was nothing artificial. Everything was as it was meant to be… There was a shepherd who was ready to lay down his soul for his sheep, and there was his flock…

While he was showing us the conditions in which people were living near the church, a young person with a book in his hands approached him and asked:

“Father, can I read this? Will you bless me?”

This question seemed so strange and out of place in that place and at that moment… But Fr. Anatoly did not find it so. He stopped, took the book out of the man’s hands, carefully paged through it, and replied:

“Yes, you can. God bless you.”

We had very little time and were in a hurry, so I did not have much time to talk to him. I told Fr. Anatoly about my desire to return and write about them.

“Why?” he asked. “Do you think it will be of use?”

Indeed, it was hardly useful for them at the time: the less the people who had set the church on fire, destroying it, remembered them, the better.

However, when he said this I was thinking about something else. Actually, I was not exactly thinking… I am not sure how to say this more clearly.

I was looking him in his eyes: they were as peaceful, calm, and infinitely deep as he himself was. In his eyes was something amazing: a meek, bright love, and a pain that was tamed and conquered by that love. Then it suddenly struck me: “This, indeed, is a martyr. A martyr!” This feeling was so strong that it completely filled me. But then it left me.

I gave him the only thing I had with me that was “church” related”: a recently-published book entitled The Great Within The Small by Sergei Nilus. In return, he presented me with a small icon of the Venerable Seraphim. And so we parted.

Our group’s mission turned out to be quite successful. We managed to meet a man named Isa in a village who was Maskhadov’s representative for such “external relationships.” We discovered unintentionally about the negotiations between Maskhadov and Gennady Troshev, who was the Russian military commander at the time. The negotiations were taking place in the same house in which we had been sheltering. We were not allowed to participate in them, of course; but, thanks to Isa, we managed to make an appointment with Maskhadov and visit the militia’s base in Vedeno the following day.

On my way there, I fell very sick: either I had food poisoning, because when we were hungry we had bought something at a spontaneously created marketplace somewhere in the destroyed Grozny, or else I was suffering from an infection. I am not certain, but I felt very bad and everything happening around me seemed vague. As if in a fog, I saw Maskhadov, who was talking with my companions in a cold building, which appeared to be a former school. Against all odds, I felt sorry for him. War is madness, especially if it has “national” implications or context. Once he joins this war, a person usually cannot free himself from this madness – even if this person had been, like Maskhadov, a Soviet officer and a patriot of his country, and not merely of his “small, but proud” historical motherland.

Through this same fog I saw Rinat (or Ruslan), who had followed us. He had come after his brother, who had been captured by Russians in Vedeno. He had been promised to have him returned. I also saw a young captured soldier, who had been released to us at Maskhadov’s command as a sign of good will. We took this soldier back with us. I also saw a healthy Chechen, who looked as if he was a sick child, who accompanied us. He told the soldiers on the road:

“Look at what beauty there is here! Come and visit us when it is all over; I will show you everything!

The soldier nodded quietly…

As sick as I was, I could not contain myself and asked the Chechen:

“What were you before the war?”

“A fireman,” he smiled.

“And what will you become after it?”

“I do not know,” he said sadly.

For some reason, I very clearly remember an episode in Vedeno. Sheynits and I were sitting on the porch of the Maskhadov’s “residence,” waiting for a car. Many people were around us, whose outward appearance made me feel uneasy at heart. This feeling only intensified in the presence of a brutal looking bearded man, who was slouching near us on the porch, pensively cleaning a huge broadsword from blood.

“It is all the Jews’ fault,” he said thoughtfully to no one in particular.

I remember that something like that was often said around Sheynits. He said the same thing he usually did:

“Well, why the Jews? I, for example, am also a Jew…”

“That is what I am talking about,” said the Chechen again thoughtfully, continuing his cleaning.

Sheynits did not continue the discussion. Nor did I have any intention of doing so.

At night, I slept very poorly in that house “on the border” of the village. I had a fever and woke up constantly with the same thought: “What am I doing here? What is the point of this?” The only point I could see was what I had run into at the destroyed church of the Archangel Michael…

This thought did not give me rest even on the plane and while we were driving from the Moscow airport, surprised that there was no war here and no ruins, but entire buildings and smiling and laughing people. And later the thought would give me no rest either.

When I was already living in the monastery, I found out that Priest Anatoly Chistousov had been captured by the militia in February 1996. He was put in a special concentration camp, where he was beaten, tortured, and finally killed. Shortly before the execution, he told his fellow inmate, Igumen Philip (Zhigulin), who miraculously survived:

“Can you imagine? If they kill us, we will be martyrs. Martyrs!..”

Translated from the Russian.