To some Orthodox it may seem that this is a somewhat bizarre issue to think worthy of an article. Indeed, perhaps it ought to be. Unfortunately, however, it is something about which there appears to be a certain amount of ignorance and confusion – to the extent where there have been very troubling instances of non-Orthodox being given Communion in Britain and other places. Where this happens, it is of course a disciplinary issue which must be dealt with by the appropriate Hierarchs. However it is also true that for some people it is an issue which is very difficult to understand – and from this lack of understanding can come an understandable pastoral difficulty when people are told that, for instance, a Catholic or Protestant spouse or friend cannot be admitted to Communion.

It is therefore my intention to try to make this subject more widely understood and, hopefully, by increasing knowledge and understanding, removing the potential for insult or offence.

Part of the reason for this confusion is that other Christian denominations allow any Christian (and, occasionally, anyone at all) to receive the Precious Gifts. Whether this is in fact true is something to which I will come later. Indeed, it seems more likely that the reason is simply that there is a lack of knowledge about the significance of Communion. This Mystery is not a cause of unity, rather a result of it.

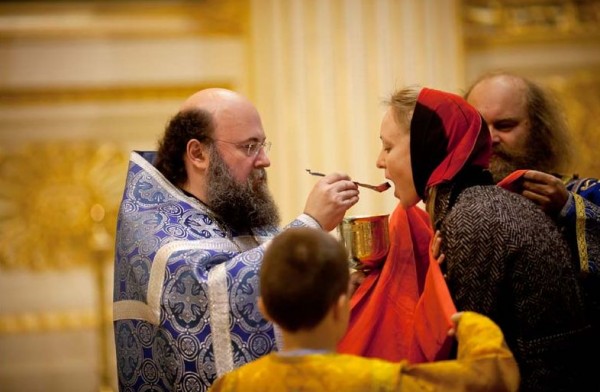

The act of receiving Communion is not something which brings someone into unity with the Church. In fact, the most serious penalty which the Church can put on its members is that of excommunication – refusing to allow an individual to receive the Gifts. This shows not only the importance of the Eucharist for Orthodox Christians, but also the fact that one must be a faithful member of the Church to take part in the Mystery.

The most significant reason for keeping a practice of closed communion is that it is vitally necessary for a communicant to have a correct understanding of the Holy Mystery from which he is partaking. As A.S. Frangopoulos explains in his book ‘Our Orthodox Christian Faith’, other Christians have an alternate – and therefore incorrect – understanding of the Eucharist. How, then, would it be at all reasonable to invite them to share, as Frangopoulos puts it, a common cup? This difference is most keenly felt when it comes to the vast majority of Protestant denominations. The Orthodox doctrine is that the bread and wine used in the Eucharist truly become the Most Precious Body and Blood of our Saviour. Most Protestants, on the other hand, tend to see this as purely a symbolic matter, choosing to concentrate on the words of Christ – “Do this in remembrance of me”. This line is, of course, only a very small part of Christ’s institution of the Eucharist.

In the account of the Last Supper in the Gospel of St John, Christ tells us that this sacrament is for the unity of the faith, that His disciples might be one. How, then, can we share this most sacred of Mysteries with those with whom we have no unity? A (rather strange, it must be said) response to this might be that “well, we are all Christians”. Only in the most basic of senses, this may be true. But we, as Orthodox Christians, believe that the Orthodox Church holds, uniquely, the fullness of truth. It carries the traditions and faith of the Apostles, and therefore springs from the salvific teaching of Christ Himself. Any theological deviation from this faith is, by definition, lacking in truth.

Another scriptural justification for the practice of closed communion comes from St Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians – “So then, whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord.” One of the reasons that this is apparently such a difficult issue in our modern, Western, society is the rise of the oppressive atmosphere of pluralism. This doctrine attempts to teach us that all opinions, beliefs and ideas are equally valid, and that it is in some sense morally wrong to question anyone else’s views or to promote a known truth of your own. Of course, as Orthodox Christians we know that this simply cannot work. There can be no such thing as a pluralist Orthodoxy. This does not, of course, mean that we should be judgmental, prejudicial or condemnatory. We are clearly commanded in the Gospel to love our neighbours, and even our enemies. It is sometimes a difficult balance to achieve, but we are extremely fortunate that we have two millennia of Church Tradition and wisdom to draw upon.

Finally, I would like to quote an extract from an online article on this subject – “It is crucial to point out that the Orthodox practice of “closed” communion is not a judgment against a person or their standing in God’s eyes or the potential of their salvation. It is not a way of saying that some are “good” and others are “bad”. The practice of receiving communion together is the outward expression of having all things in common, in faith and worship. It is the fruit of unity.”